A Métis French stress pattern and Chinook Jargon

I have a simple insight to share today.

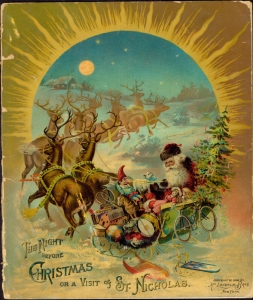

(là)nowél (Image credit: Vancouver Métis Citizens Society)

This one is somewhat speculative, not proven. But it would fit with the growing array of evidence that Métis people’s speech enormously influenced the formation of Chinook Jargon.

There are 3 major dictionaries of the mixed Cree-French language of the Red River Métis buffalo hunters, Michif.

- One of them is Laverdure & Allard’s really fine 1983 Turtle Mountain (North Dakota USA) book, unfortunately out of print, so head to a college library to do some copying.

- A second is online, free of charge, from the Algonquian Language Atlas; it’s Canadian…it’s text-only, and I think it’s the smallest of the 3 dictionaries.

- The third is free and online too, Norman Fleury’s 2013 Michif dictionary from the Gabriel Dumont Institute in Manitoba Canada. What I’m appreciating about this hefty resource is, every entry is linked to an audio file that lets you hear a native speaker pronounce the word or phrase.

And when I listen to the entries in the Fleury 2013 MIchif dictionary, I’m struck by a particular rhythm that the language has.

In particular, the French-sourced nouns that are cited with articles (definite or indefinite ones), tend to stress those.

At least, the articles typically receive a secondary stress, [à è ì ò ù] etc.; the noun still receives the primary stress, [á é í ó ú] etc., as we’re accustomed to in other French varieties.

In those varieties, though, my perception has always been that articles le(s), la, un(e) don’t receive enough stress to be worth commenting on, and that it’s the final syllable of French words that typically takes the main stress. (I always admit I’m more of a reader than a speaker of French, so, readers, please correct me as needed!)

Examples (using ~ to indicate a nasal vowel, and : to show vowel length):

- < li glaand > ‘acorns’ [lì:glá:~d]

- < la lavet > ‘terrycloth’ [làlavέt]

- < li laavmaen > ‘basin’ [lὶlavmέ~]

- < aen piikap > ‘cap’ [ὲ~:piká:p]

- < enn modeuz > ‘seamstress’ [ὲ:nmɔdýz]

(This same pattern encompasses possessed nouns. This finding shouldn’t surprise anyone who’s had a good basic linguistics course or two, because “possessive pronouns” in French share a trait with articles, marking a noun as definite. Also taking secondary stress are other particle-words that attach to the beginning of a following French-derived word, e.g. the negative particle < pa > and the preposition < aan >:

- < toon vanntr > ‘abdomen’ [tò:~vá:~tr] (literally ‘your belly’; in Michif, body parts are inalienably possessed, so they’re always spoken of with the words for ‘my / your / her’ etc.)

- < pa finii ‘not finished; underdeveloped’ [pàfiní:]

- < aan disoor >’underline’ [à:~dιsó:r] )

There’s an intonation thing going on here, as well. The articles in these words have what I’ll vaguely call a higher pitch than I’d expect if they were unstressed.

Additionally, I’m thinking “syllable count” plays a role, such that it’s preferred to alternate stressed and unstressed syllables throughout a phrase. The article isn’t stressed (nor is its vowel lengthened) in the following examples, where (A) there’s no possible unstressed syllable between it and the primary-stressed syllable of the noun and (B) an alternating-syllables stress pattern (oriented from the main-stressed syllable) mandates an unstressed article:

- (A) < enn cheuk > ‘toque’ [εnčý:k]

- (B) < la rilizhyoon > ‘theology’ [larè:ližyó~]

However, I do perceive secondary stress (and vowel lengthening) on the article in this one:

- < enn pyiizh > ‘trap’ [ὲ~:pí:ž]

— So, with one-syllable nouns, maybe there’s also a consideration of “heaviness” as well, wherein a voiced final consonant such as [ž] makes a syllable heavy (counting as 2 “moras”?), as contrasted with the voiceless [k] in the previous example.

Then again, not every noun of 2+ syllables has a secondary-stressed article in its audio file. I notice for instance,

- < la michinn > ‘medicine’ [lamιčίn]

Is some of the above-described Michif stress pattern one of the signs of influence from the Plains Cree half of Michif?

I wonder whether this Michif tendency of stressing definite articles carried over from Métis French.

My point today, anyhow, is to wonder if this pattern influenced the formation of Chinook Jargon. It might have arrived via Métis French directly, or via the then-young Michif language (mixed Cree-French), or both…

…Particularly around 1825, when the Jargon rapidly became a home language of Métis famlies in the Pacific Northwest.

When we look at the phonetics of the numerous (Métis-)French-derived nouns in the 2012 dictionary of Grand Ronde Chinuk Wawa (a community that we know historically includes Métis people), many of these words allow, or even mandate, the main stress to be on what was originally a definite article. (I’ll show the various documented primary-stress locations all with acute accent marks.) Examples:

- lílu ‘wolf’

- límá ‘hand’

- lápʰusmu ‘saddle blanket’

- lákamás ‘camas’

- límotó ‘sheep’

(Indefinite articles from French have not been preserved in Chinuk Wawa.)

There are hardly any French-sourced CW words longer than 3 syllables in the 2012 dictionary that are supplied with notations of elder speakers’ phonetics. This tells us very little about the broader pattern we’re investigating. I’m just finding libárədu ‘shingle(s)’, but note the variation in George Gibbs 1863 < le-báh-do > / < láb-a-do >.

Does the hitherto unexpected & unexplained Chinuk Wawa stress variation in originally-French “definite article + noun” formations trace to Métis roots?

I’m inclining towards thinking so. There are quite a number of other Métis traits in the Jargon, and there’s a demonstrable strong association between this language and those people.

Brilliant. If I understand correctly, my surprise in hearing old recordings with LEEma or even LEEmai could come from the Red River. -mai would preserve Canadian French diphthong. I wonder if the Chinook Jargon question particle is connected to the French negative particle ne

LikeLiked by 1 person

I feel like I’d have to squint hard to see a resemblance or connection between French “ne” (as in “n’est-ce pas”) and Chinuk Wawa “na”. For me, French “hein” would be a better match…but still implausible.

Not sure what I think about the /ai/ in the Jargon corresponding a couple of times in old sources to Canadian/Métis French < ain >. One thing that gives me pause is that Interior tribal languages that borrowed words from that those French speakers seem to have /a/ instead, e.g. ləpa ‘bread’.

LikeLike