Howay [Haswell, Boit, Hoskins] “Voyages of the Columbia” (Part 2B of 5)

Continuing to examine John Box Hoskins’s 2nd NW coast journal, I ask you: Is there much communication here that can’t be explained as the use of a lot of gestures and a few words?

That is, was there a pidgin in existence in these places in 1791-1792?

This is all taken from F.W. Howay [editor], “Voyages of the “Columbia” to the Northwest coast, 1787-1790 and 1790-1793” (republished 1990).

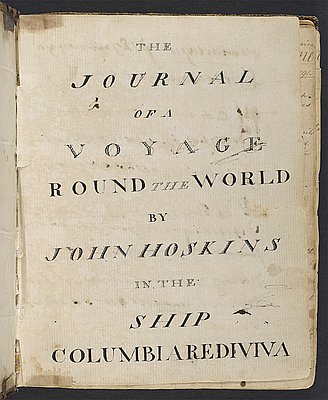

Part 2B: The journal of John Box Hoskins

Image credit: The Oregon Encyclopedia

The next day (p. 220) we see that relations between Haidas and Tlingits in modern southeast Alaska aren’t wholly peaceful (historians tell us the Haidas had invaded in recent generations) — the mariners don’t understand much of what’s going on, admitting that they know extremely little of the language(s):

In the afternoon there was a large canoe full of natives entered the Sound Clinokah on seeing it appeared to be quite frantic running about the decks like a madman calling to his canoes that were ashore to come of and requesting us to fire at the strange canoe and support him for he said they were coming to kill him as soon as his canoes came of the natives came on board drew their daggers ran fore and aft brandishing them bawling most vociferously and offering by the most threatning motions and gestures every possible insult to these strangers having but a superficial knowledge of their language of course we could not so well know what might be their intentions they were therefore all but the Chief sent into their canoes

Pages 220-221, after peace has been made between the two groups of Native people — the mariners are utterly unable to communicate with the newly contacted Tlingits, relying on a Haida chief to interpret:

Matters to appearance being thus happily adjusted Clinokah introduced to our acquaintance this new Chief with whom we could not speak a word as he talked a language very different to what any of us have yet heard he brought several fine skins which were soon purchased as Clinokah was good enough to be our interpreter and to trade for him.

The morning of the 12th was calm and pleasant at sunrise one canoe came alongside in which was six men (extraordinarily well armed with spears daggers bows and arrows covered with mats in the bottom of their canoe this I did not know till long after they had gone) they sold two small skins and invited me to go on shore to take breakfast with them on roast fish and berries this I declin’d though not suspecting any ill design they had after baiting Mr. Caswell’s fish hook according to their mode they went ashore abreast of the ship as they said to get skins but we saw no more of them.

Page 223, the 15th of August, 1791 — another of the many instances where Hoskins confesses the Euro-Americans know hardly anything of the tribal languages and can’t effectively communicate:

It will no doubt be recollected under what circumstances we entered the Sound the untoward ones which followed together with our small intercourse with the natives and imperfect knowledge of their language gave us no opportunity of gaining any knowledge of ourselves or determining with any precission on that derived from the natives of the extent of this Sound.

The natives (same page) “informed me [there] was a village called Cahta” on Kasaan Bay, modern Prince of Wales Island, Alaska.

Page 224, regarding the Haidas of Cholmondeley Sound, yet another of the several explicit disavowals of having much understanding of these people:

Little knowledge can be expected for reasons before given as to their numbers manners or customs

On page 226, with these same Northern Haidas, it’s accurately recognized that “Their language and dress is very similar to what we have heard and seen at Washington’s Islands…” [Haida Gwaii]. This level of linguistic sophistication, at least, is constant through the earliest Euro-American journals. The newcomers typically were able to tell which languages were greatly dissimilar or unrelated to each other.

Another Native person rated as “very intelligible” by Hoskins (page 228, August 18) in the Massett, Haida Gwaii area is a chief of Kaigani (Dall Island in modern Alaska) — I can imagine the Native folks shook their heads at the Whites’ dumbness, imagining that a freshwater river and lake might be a shortcut to sail to the opposite side of an island! We have to rate the following as a major failure to understand what the Haida chief was saying:

a few natives visited us with skins among others was a Chief named Kow belonging to Clegauhny a tribe so called who inhabit a bay to the westward of Brown’s sound this man was very serviceable to us in trade and very intelligable he informed me this river ran some distance into the country terminating in a lake which was supplied by a number of small rivulets which abound with salmon round this lake are situated their villages as I had an idea this might afford a passage through to the eastern side of the island I questioned him on that head his answers were so very clear that I have no longer a doubt of its being anything more than a river as he described.

Page 229 mentions learning from the Haidas that a place Hoskins calls Cape Lookout has a Native name of ” ‘Naikoon’ or ‘whale point’ “. He also learns of the Haida place name “Masheet” (Masset). Baby stuff, among the easiest communication to achieve.

Page 230, not clear whether the source of information “I am informed” by here is Euro-Americans or Natives, and Hoskins disavows confidence in his having understood what Native people were saying:

The tribe which inhabits this river I am informed is large though we saw but few natives their Chief is named Cuddah this tribe at some seasons of the year afford many skins I suppose indeed if I understood the natives right they are moved up the river for the benefit of fishing as they have parted with all their skins but what they want for winters clothing.

On page 231 chief Comsuah (Cumshewa) visits, August 22, 1791, again with merely a fundamental level of trading-related information getting across:

…informed us there was but few skins at his village at present yet if we would wait ten days they would procure a plenty pointing towards the Continent and giving us to understand ’twas from that quarter he would get them.

On page 233, among other places, we see that Hoskins is like other early maritime fur trade visitors in being well-informed of other ships’ visits, having read the available journals as well as constantly encountering each other on the PNW Coast throughout his narrative.

On page 235 Hoskins expresses having taken the Haidas as reporting that their overall chief is “Cunniah…of Tahtence” (Dadens), that they govern themselves as a matriarchy, and that they believe in some kind of sky god who guides their course through any bad weather. Again, Native people may have been astonished at the naive thinking of the Whites, who failed to grasp Indigenous familiarity with tides, currents, and other navigational clues:

The government of these people appear by no means to be absolute the Chiefs having little or no commands over their subjects Cunniah the Chief of Tahtence is acknowledged to be the greatest on the Islands his wife of course must be the Empress for they are intirely subject to a petticoat government the women in all cases taking the lead.

That these people trade with those over on the main for skins etca. is certain but as one shore cannot be seen from the other at Tooschcondolth over it surprizes me what guide those natives could have had who visited us there when it was foggy at the time and had been for several hours before so that they could not have an opportunity of being directed by the stars which makes it the more wonderful in all probability there is yearly many overtaken by storms and lost indeed the natives have informed me that is sometimes the case on asking Comsuah what guide they had to direct them he would answer by pointing up to the heavens on telling him it was thick and they could not see he would still answer by pointing up to heaven intimating thereby that there was one above who would always guide, protect and direct them that was good.

Pages 235-237 evaluate the Haida language and its dialects (as always, noticing the similarities among dialects), providing a nice word list:

The manners, customs, dress, canoes etca. etca. of these people are all similar their language differs only in a few words in the termination of some words they have or make a long quivering which gives them a most savage disagreeable sound but to convey a better idea I here subjoin a list of words I was able to procure which are spelt as near to their pronunciation as my ear would direct which I am conscious is far from being right.

A number of the words in Hoskins’ Haida lexicon are of interest to us, in light of the question of whether there was a pidgin in existence or coming into being on the Northwest Coast in 1791.

- Editor Howay correctly points out the word for ‘bad’, Peeshuck / Peesuck (the latter being more Haida-accented), as coming from Nuuchahnulth or the presumed “Nootka Jargon”.

- But we should also take note of his Scemokit ‘a Chief’ (from a Tsimshian language), his Haida Cahtah/Ketah ‘to Eat’ (compare his Cahta above as the supposed name of a Haida village — was it being described as a place with plenty of “food”?);

- his Wakun ‘a term of friendship’ (compare Nootka Jargon wakash?),

- his Sumun (compare English small),

- his Tsook/Too ‘to Discharge a gun or bow’ i.e. ‘to shoot’ (compare Nootka Jargon p’u, because Haida almost entirely lacks /p p’ b/ sounds — I make a similar argument about Haida/Tsimshian/Tlingit duus(h) ‘cat’);

- his Come/No (the first is Haida but the second would be from English),

- and of course his final word Elieu ‘I’ve got no more’ (native Haida, this became Chinuk Wawa hilu ‘no; none’).

I don’t see the presence of these words in Hoskins’s Haida vocabulary as proof of an existing, stabilized Haida (or other) pidgin, however. They can just as easily reflect the ultra-low level of verbal comprehension between the two cultures at that moment, stimulating the enlistment of any and all linguistic resources that achieved some mutual understanding. The great bulk of the following word list is probably perfectly good Native-speaker Haida, albeit often misunderstood by the visitors.

On page 238, on August 29, 1791, the ship arrives at Clayoquot on Vancouver Island (“Cliquot”):

at four several canoes came of in one of which was our old friend Hanna he informed us Captain Kendrick was at Clioquot in a Brigantine and had been there some time

Page 240, a recent incident in Haida Gwaii, in which Natives steal some linen “etc[eter]a.”, is reported to Hoskins by Captain Kendrick — some of the supposed reported dialogue was plausibly delivered in gestures as much as, or more than, in words:

…

this with some other things they had at times robbed him of induced him to take the two Chiefs Coyah and Schulkinanse he dismounted one of his cannon and put one leg of each into the carriage where the arms of the cannon rest and fastened down the clamps threatning at the same time if they did not restore the stolen goods to kill them

…

…the two Chiefs were set at liberty when he went into the Sound this time the natives appeared to be quite friendly and brought skins for sale as usual the day of the attack there was an extraordinary number of visitors several Chiefs being aboard the arm chests were on the quarter deck with the keys in them the gunners having been overhauling the arms the Chiefs got on these chests and took the keys out when Coyah tauntingly said to Captain Kendrick pointing to his legs at the same time now put me into your gun carriage

The narrative of the ensuing violent melee, encouraged by a Haida “amazon” who winds up with one of her arms cut off, closes with “This accounts for the story the natives told us when we were there.” (P. 241) As always, let’s silently add the disclaimer, “…as we understood it!”

Stunning to me is page 242’s comment that Capt. Kendrick bought Nuuchahnulth people’s “landed estates”, also expressed as their “land”, italicized in both occurrences. One can wonder to what extent these Native folks saw these transactions as conveying anything like Euro-American “title” to something as valuable and durable as real estate.

Page 242 has Hoskins’ people catching sight of two large unflagged vessels; the Nuuchahnulth locals “informed me they were not Spanish nor English as these people are acquainted with both those nations”. This is extremely basic and easily conveyed information.

Pages 242-243, the Nuuchahnulth say the fundamental information they have few skins, “having previously sold them to Captain Kendrick but now they would sell the few remaining to him who gave the best price.” This is at the end of August, 1791.

Page 245 at Archawat in Makah country on the modern USA side of the Straits of Juan de Fuca, September 1791 — a somewhat involved narrative from a chief who has had substantial dealings with the Spaniards, and is able to sing Christian songs in “broken Spanish and Indian”, the latter perhaps resembling the couple of seemingly Nootka Jargon song lyrics we know to have been composed by Spanish & English-speaking visitors — but Hoskins is not confident he understands this man:

at nine there being a strong tide against us we cast anchor before the village Ahshewat in twenty five fathom water over a muddy bottom Tootooch’s Island bearing north one league distance several of the natives visited us with skins which were purchased among others was a Chief named Clahclacko who from what I could understand wished to inform me the Spaniards had been here since us endeavouring to convert them to christianity that he and several others had been baptized as also several of their children this ceremony he went through as also the chanting of some of their hymns with a most serious religious air though it was in broken Spanish and indian yet he imitated the sounds of their voices their motions and religious cants of their faces to a miracle at the same time condemned our irreligious manner of life.

Page 247 “Clicksclecutsee” is understood to be the name of a cove near Opitsat village on Vancouver Island.

An unrelated note of interest is Hoskins’ description of “Inistuck” in this vicinity as “a clever snug cove” (page 249). I expect “clever” here is equivalent to our modern English word “cute”, which comes from earlier “acute”. That word originally meant “clever”, and it was synonymous at the time with “cunning”, when describing the adorableness of babies and so forth.

Pages 249-250 — one of the sailors sees what Hoskins takes to be an alligator (!) in October of 1791; what follows is one of the earliest written descriptions of a “sisiutl” and a Nuuchhanulth offer of “twenty” sea otter pelts for one (their Indigenous number system being Base-20, thus this was a generic offer of “a heck of a lot”; compare their word for ’10’ which became Chinuk Wawa’s ‘a lot’):

I have since informed the natives of what was seen who inform me there is an animal which from the description of them as they are painted on their canoes as also one they drew with chalk on board the ship as they are pretty good imitators can’t be far from the thing and are very different from the alligators found in the southern parts of our side of America these having a long sharp head something like a hound with a good set of teeth the rest of the body in every respect like a serpent it is called by the natives a Hieclick and by them very much reverenced they tell me this animal is very scarce and seldom to be seen living principally in the woods they offered me twenty skins if I would procure them one for they have such a superstitious idea that if they should have but the least peice of this animal in their boat they are sure to kill a whale which among them is deemed one of the greatest honors indeed a peice of this magic animal insures success at all times and on all occasions.

Page 250 has an interesting account of someone telling a lie in Nootka Jargon, or signs, or some such medium!

he then pointing his gun at the chief ordered them to desist and go of or he would immediately fire upon them they then agreed if he would tell them where Captain Gray was they would go he told them down to Opitsitah where he was not they left him…

On page 251 (October 21, 1791), chief Tootiscoosettle “requested the loan of two long poles” for what turns out to be harvesting “sardines” at the beach with “green boughs”. These latter bring traditional herring-spawn harvesting to mind, but Hoskins says the Nuuchahnulths drove the fish onto the shore to eat them. Neither this nor the following transaction need have involved many words whatsoever…

On page 252 (November 19, 1791), “we were visited to day by some few of the natives from the Ahouset tribe to whom we expressed our want of oil for lamps this want they soon supplied by daily fetching of it to us in large bladders made from the intestines of some fish…”

I definitely believe there was no established pidgin language known all over the northern PNW coast yet. There was no Chinook Jargon in these places. (Nor do we have evidence of it anywhere else so early.) The “Nootka Jargon” was still pretty incipient and formless.