North American French pronunciation habits help explain Jargon “R-dropping”

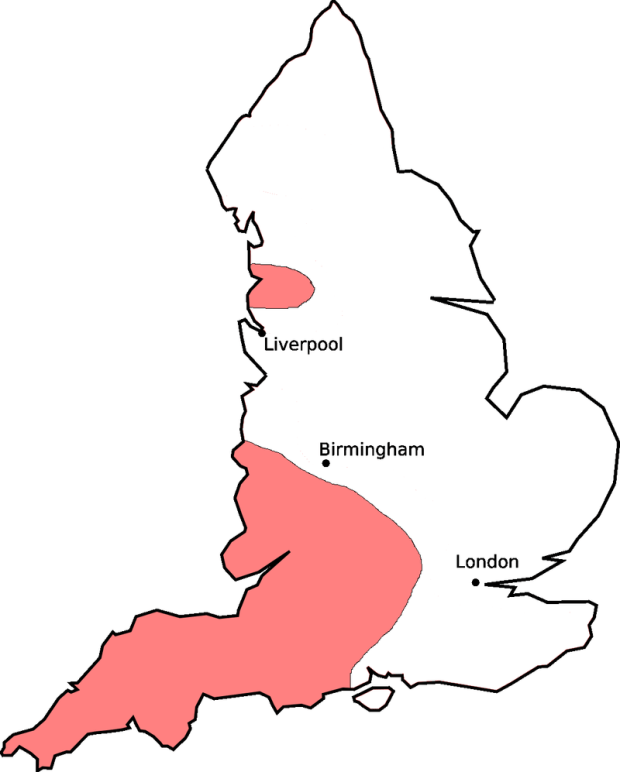

Non-R-dropping areas of England (pink) in the late 20th century (image credit: Wikipedia)

Chinook Jargon doesn’t “drop its R’s” nearly as often as the “R-less” English dialects do…

…For an example different from the above graphic, most Australians don’t pronounce an R-like (rhotic) sound at the end of any syllable or word. (I.e. directly following a vowel.) “Barbie” is “bahbie”, and “tucker” is “tuckah”.

In the same positions CJ, by contrast, says lárp for a smoking mixture / tobacco substitute, lapárp for ‘beard, and nipərsi for the Nez Perce tribe. This is the Grand Ronde dialect we’re talking about at the moment, by the way.

Besides, the Jargon can say its “R” sound at the beginning of a syllable, i.e. directly preceding a vowel. I’ve written up a whole article about that, to point out why it’s weird that the word for ‘French’ is pʰasáyuks instead of pʰrasáyuks / pʰlasáyuks. There are lots of CJ example words such as lariyét ‘lariat’, ráwn ‘around in a circle’, drét ‘right’, liprét ‘priest’, and likʰrém ‘a horse color’.

But there is one highly specific environment where Chinuk Wawa has gotten rid of “R” sounds that used to be there, in the languages that donated those words. That’s when the “R” (or “L”) fell right after a “stop” consonant (P, B, T, D, K, G, and such), at the end of the word.

For a demonstration of that, we can look at the one phonetically well-documented variety of French in North America, at least in my personal research library 🙂 That’s the French-Cree mixed language Michif, which shares some historical roots with Chinook Jargon…

STANDARD FRENCH MICHIF CHINUK WAWA

le prêtre li pret liprét

la table la taeb latám / latáb

le diable li Jiyawb lidjób

l’Ordre ………… lód

les apotres ………….. lisapot

ONE COUNTEREXAMPLE THAT PROVES THE RULE:

le sucre li seuk ləsúkʰər (but this is thought to have been influenced by English ‘sugar’!)

I have no real doubt that “R’s” get dropped in this same position in much of Canadian and North American French, too. It’s just that the reference materials I’ve got hold of don’t tell you so much the pronunciation as a standardized spelling of each word 😦

The point remains, that Chinuk Wawa’s French words tend to show (in many ways including today’s minor R-dropping note) a consistent historical link with Canadian / Métis French above all other types of French.

This occurs throughout the Francophonie, outside of higher registers, at least when people speak fast. It’s by no means specific to America.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s my impression from exposure to lots of French-based creole languages!

LikeLike

Dave, David: Loss of final liquids (when preceded by a consonant) indeed occurs throughout the French-speaking world, but this phonological feature was absent from the colonial French first brought to New France and the West Indies (Trust me on this: my own as-yet unpublished research on Early French loanwords in languages spoken along the Atlantic facade of the Americas makes it clear both liquid phonemes were alive and kicking in final position after a consonant), and I am uncertain as to whether the later presence of this change in North American French varieties is due to diffusion from Europe or to a parallel change (a case of Sapirian “drift”, if you will).

Dave: the ubiquity of the change in French-based creoles means little, as there is good linguistic evidence that all known French-based creoles have a single common ancestor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m getting some superbly helpful comments on these French-related posts, so my thanks to you, Etienne, for participating in my research!

LikeLike

I agree with David M and Etienne, but they give no examples, so here are a few that I (a speaker of Northern European French) could use in relevant situations without thinking (the parenthetical re and le here are normally omitted in these phonological contexts):

“une liv(re) de sucre” ‘a pound of sugar’

“un liv(re) de cuisine” ‘a cookbook’

“une tab(le) de nuit” ‘a night table’, “la tab(le) des matières” ‘the table of contents’

“pas capab(le) de le faire” ‘unable to do it’

“septemb(re), octob(re), novemb(re), décemb(re)”

I have heard the following phrase pronounced as a joking example of this: “une demi-liv(re) de suc(re) en poud(re)” ‘a half pound of granulated sugar’, where “suc’ ” sounds illiterate, and “poud’ ” just slightlly less so.

Only in Southern French (heavily influenced by the Occitan substrate), in which postconsonantal final e is always sounded, are the re and le fully pronounced in the above context as in most others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And is North American French particularly descended from Northern European French?

LikeLike

Dave: No, because in the seventeenth century French as an L1, in France, was only spoken in Paris and surrounding rural areas: the North/South accent split within France arose later (nineteenth century), as a consequence of the spread of French within France via the usual suspects (obligatory schooling, urbanization, military service, sharp rise in social and geographical mobility…). Laurentian French (=Quebec and everything further West) , as well I might add as the French that gave rise to French creoles, is transplanted Parisian French, pure and simple (whereas Acadian French is Parisian French with a strong dialect [Poitou-Saintongeais] substratum).

Laurentian French thus derives from Parisian French by definition (since French as an L1 was only spoken in Paris at the time), but it has also been shown to derive specifically from the pre-revolutionary aristocratic standard (which, before the French Revolution, co-existed with a distinct standard used by the bourgeoisie: both standards differed chiefly in pronunciation). After the French Revolution (and the resulting annihilation of the aristocracy), the latter became the only standard, first in France, then throughout the French-speaking world: as a result many colloquial/popular phonological features in North American French which are considered vulgar today are features which were specifically aristocratic in seventeenth-century Paris.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a good historical linguistics lesson! Hayu masi!

LikeLike