A Quinault Salish etymology for ‘sea otter’?

Great-grandparent face (image credit: Howling Pixel)

Chinuk Wawa’s < elackiè > is a rare word, but it has outsized historical importance.

The only original documentary source that I’m aware of for this word in Jargon (also spelled < e-lakʹha >, at least in Edward Harper Thomas’ 1935 compilation of older sources) is Alexander Ross (1849).

With that “E” sound at the beginning of it, we’d expect this to be a Chinookan word. We do indeed find it in that language family, but only in the one language that actually has seashore territory, Shoalwater-Clatsop. Further inland, Kathlamet reveals only ‘land otter’; no words for otter are evident to me in Clackamas & Wishram:

- Shoalwater-Clatsop (Boas 1910): i-láki, i-i-laki (which looks like Chinuk Wawa’s ~ ilaki (re-)nativized into Chinookan), plural i-lagít-ma (the “T” is unexplained and interesting)

- Kathlamet (Boas 1894): only plain ‘otter’ is mentioned in the English translations, and the Kath. word, í-nanaks, is a better match for Chinookan-derived Chinuk Wawa nanamuks ‘land otter’

- Clackamas (Jacobs 1958-1959): no ‘otter’ found

- Wishram (Sapir 1990): no ‘otter’ found

Verne F. Ray’s “Lower Chinook Ethnographic Notes” (1938:114) confirms the important role of the easily caught sea otter in traditional culture there, being used for valued robes that are mentioned by all early European sources.

So far so good.

But now, compare Shoalwater-Clatsop Chinookan with nearby Quinault Salish (I’ve turned Ruth Modrow’s older-style writing into phonetics) :

- nəw=álaqi

best=hair

‘fur’ [specifically of sea otter?]

(Here I gloss the root nəw as ”best’ because, across the SW Washington Salish (“Tsamosan”) languages, it tends to be used in words for the best exemplar of a class, and it appears to trace back to Proto-Salish *wənaxʷ ‘real, true’.) - ƛ̓əq̓ʷ=áləqi

good=hair

‘sea otter’ - ƛ̓əq̓ʷ=ál̓əqn-uʔ

good=hair-DIMINUTIVE

‘little sea otter’

‘Little sea otter’ shows that Quinault’s suffix =aqi ‘hair’ is underlyingly =aqn. An “N” sound at the end of a syllable can “vocalize” in many Salish languages; here it turns into an “I”. This suffix goes all the way back to Proto-Salish *=al ‘Stem Extender’ plus *=qin ‘head (hair, top; throat, voice, language)’, and is not to be confused with the unrelated Nuuchahnulth -aq ‘hide, fur’, despite the resemblance to Nootka Jargon k̓ʷaƛaq ‘sea otter pelt’. (But keep reading for a further mention of that word!)

Having explained that, let’s compare Lower Chehalis Salish, where we at least know that the word for ‘sea otter’ is related to the Quinault ‘good hair’ one…except that here — pay attention — there’s no “I” at the end:

- < klû-kwa-ûlk > (Myron Eells, 1880s)

- < tľaǩ͓ʾoāʹle̳k͓ > (Franz Boas, 1890s)

- < ʻla-qálk > , < tláqala > (Edward S. Curtis, 1907)

- ƛ̓əq̓ʷ=áləq , ƛ̓əq̓ʷ=ál̓əq (John P. Harrington, 1941)

Therefore, it sure looks to me like the already bilingual Chinook(-Chehalis) people in frontier times, in their role that’s been characterized as trade middlemen, might’ve been getting sea-otter skins from Quinaults to sell to the fur companies. They would’ve easily known enough Salish to

- (A) ask for the item by name (nəw=álaqi, ƛ̓əq̓ʷ=áləqi, etc.) in Quinault,

- (B) identify nəw and ƛ̓əq̓ʷ as separable roots (because the same roots are used in Lower Chehalis),

- (C) (mis)perceive the Quinault Salish (=)álaqi as a freestanding noun which just so happens to be formed like a Chinookan noun

- (a- being a feminine noun gender marker,

- leaving an apparent root laqi),

- (D) then for whatever reason assign a “correct” Chinookan masculine noun gender marker i- to it,

- (E) resulting in the word < elackiè > that came into pidgin-creole Chinuk Wawa,

- (F) and even, by 1890 when Charles Cultee tried teaching Lower Chinookan to Franz Boas, some of the time they’d put another copy of that i- onto it, to emphasize that it’s considered a Chinookan noun, thus i-i-laki.

Note that there’s a “K” instead of the expected original “Q” in the Lower Chinookan word. Aside from the known existence of “augmentative/diminutive” alternations between those two sounds in that language, a smart explanation remains to be found for this.

Another important thing to notice: all Lower Chehalis references I’ve seen to sea otters specifically mention Quinault country! Emma Luscier told John Peabody Harrington:

“There used to be a lot of sea-otters in front of Tahola all the way from Tahola to Damon’s Point. ”

Land otters are the only kind said to be native to Lower Chehalis country, which, remember, is shared with Shoalwater-Clatsop Chinookans. This blended population were the earliest groups to have significant interactions with Europeans leading to the formation of Chinuk Wawa. Or as I’ve been leaning towards calling it, Chinook-Chehalis Jargon.

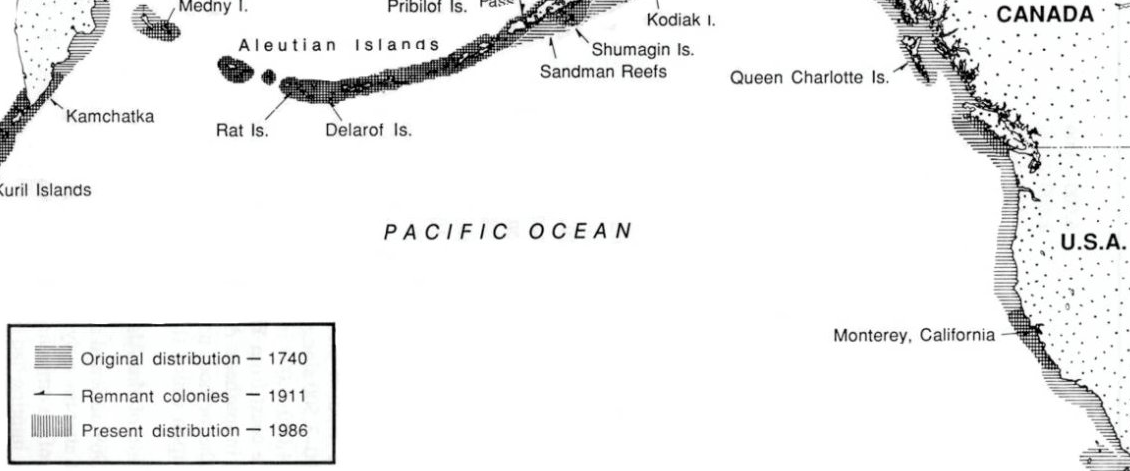

The aforementioned remarks by Lower Chehalis speakers are valuable ethnobiological observations. No local gap in sea otter habitat is evident from expert sources I’m finding. Those just make a crude distinction between precontact and recent times:

Sea otter range (image credit: IUCN Otter Specialist Group)

Mind you, I’m told by Lower Chehalis/Chinook personal connections that sea otters are historically remembered in that country, and also that the animals now live there. I’m just wondering if they got “hunted out” into local extinction during the fur-trade era that was of course centred around the Columbia River estuary.

Speaking of geographic distributions, this particular Salish expression for ‘sea otter’, using a suffix =álaqi ‘hair’, is not found in the inland southwest Washington Salish languages:

- Upper Chehalis: p̓ítkʷł (this looks analyzable; provisionally I suspect it’s a descriptive word meaning a ‘covering’, thus something like a sea-otter robe/cape/blanket; if so, the vowel makes it look like a Lower Chehalis loan)

- Cowlitz:

- p̓ítkʷł (see preceding comment)

- s-kál=mn (also analyzable and it looks like words for cultural items rather than animals, but the meaning of the root kál is not yet known)

One reason for the variety in SW WA Salish words for ‘sea otter’ is that it’s not a terribly old concept in Salish.

That must sound strange. But aside from the ethnographic testimony of sea otters’ absence from areas near the Columbia River, there exists other evidence for that claim.

No word for any ‘otter’ is reconstructed for Proto-Salish in Aert H. Kuipers’ 2002 “Salish Etymological Dictionary”. And M. Dale Kinkade similarly has no ‘sea otter’ term reconstructed in his 1990 study that locates the Proto-Salish homeland somewhere near the Fraser River estuary.

(Another way to think of this is that any modern-day Salish language that has a word for ‘sea otter’ — Lushootseed, in the ancient homeland zone, apparently lacks one — is likely to have one that differs from its sister languages, for example Klallam’s č̓aʔmús, thought to mean ‘great-grandparent face’.)

The above map seems to indicate no sea otters in those inshore “Salish Sea” waters; other sources back this up.

Now, Chinookans and Salish people weren’t the only occupants of this stretch of coast. Sea otters also were historically harvested just north of this Salish language group, in neighbouring Quileute country. But the relevant words in Quileute (an unrelated language) are poor candidates to have been a source for < elackiè > :

- łapk̓is ‘skin, hide’

- -dis ‘skin’ (lexical suffix)

- hí•dis ‘skin of fur-bearing animal’

- xʷoxʷó•dis ‘skin, pelt’

- -q̓ʷał ‘fur’ (lexical suffix)

I just don’t see much potential for a Quileute explanation of the Chinook Jargon word. And Quileute contributed no known words to CJ.

Mind you, neither did Quinault. But, by contrast, I find the close resemblance between Quinault Salish and the Chinook Jargon word can’t be discounted.

Granted, < elackiè > is not a well-known word in Jargon documentation. It’s known to me only from the earlier, lower Columbia region, and therefore almost certainly would’ve gone out of use once this animal became locally scarce. Not to mention that the center of gravity of the language’s use in that region shifted a bit southward and away from the sea, to Grand Ronde reservation in Oregon.

Around the same time that those events were going on, Chinook Jargon was being abruptly transplated northward to British Columbia, leading to what I’ve called a “bottleneck” event where much of the lexicon was jettisoned. Sure enough, in BC Jargon of those later decades, you can find both a Salish word lahac and the English word otter borrowed to fill the resulting gap. (See”Raw Furs. — Read This!“)

Having shifted forwards in time there, let me now wrench you to an era earlier than < elackiè >. Because there is more than a passing resemblance between the Salish sea-otter words meaning ‘good hair’ (ƛ̓əq̓ʷ=áləqi etc.) and the decidedly older (say 1770s-1820s) Nootka Jargon word for it. As I’ve previously written (see “Cutsarks?“), k̓ʷaƛaq ‘sea otter pelt’ in that earlier pidgin is easily analyzable in the unrelated Nuuchahnulth language as literally ‘sea otter pelt’. (Amazing, eh!)

And it turns out, from page 349 of his book, that Alexander Ross himself used not only < elackiè > but also < quatluck > (i.e. k̓ʷaƛaq) as Chinook Jargon words for this! This suggests a speculation to me.

There was an intense sea-otter “rush” by maritime fur traders, centering originally on Vancouver Island, before 1800. Had those visitors’ Nootka Jargon word k̓ʷaƛaq become widely known outside its original Vancouver Island region, at least down the coast to Quinault country, and perhaps as far south as Chinook-Chehalis territory, by the time overland fur traders like Ross and fellow Astorians were working in the Columbia’s estuary?

I muse about the chances of “k̓ʷaƛaq” having been the ultimate inspiration behind Salish ƛ̓əq̓ʷ=áləq(i).

Questions occur to me around the above-mentioned Quileute -q̓ʷał ‘fur’ (lexical suffix); could Nootka Jargon “k̓ʷaƛaq” have been the inspiration behind that affix as well? We know seagoing Whites were trading with Quileutes by 1792, cf. John Boit’s report of visiting “the Village Goliu“.

In any case, a Quinault source for any Chinook Jargon word is a great novelty, coming as close as you’ll get to “breaking news” in this area of study!

Surely that’s enough etymologizing for a day.

.

Pingback: Hidden discoveries: Extinct animals & creole-pidgin ethnozoology (Part 2) | Chinook Jargon

Pingback: sup-uk from Salish & Chinookan, but really Salish | Chinook Jargon

Pingback: More about the early-contact origin of elackiè ‘sea otter’ | Chinook Jargon