WA: Is “Tsako-te-hahsh-eetl” Chinuk Wawa?

Is “Tsako-te-hahsh-eetl” Chinuk Wawa? Nope.

But what a great question!

It’s ɬəw̓ál̓məš a.k.a. Lower Chehalis Salish, though, and as such, it’s a valuable piece of data on that relatively little-known language that became a co-ancestor (alongside Lower Chinookan) of Chinuk Wawa.

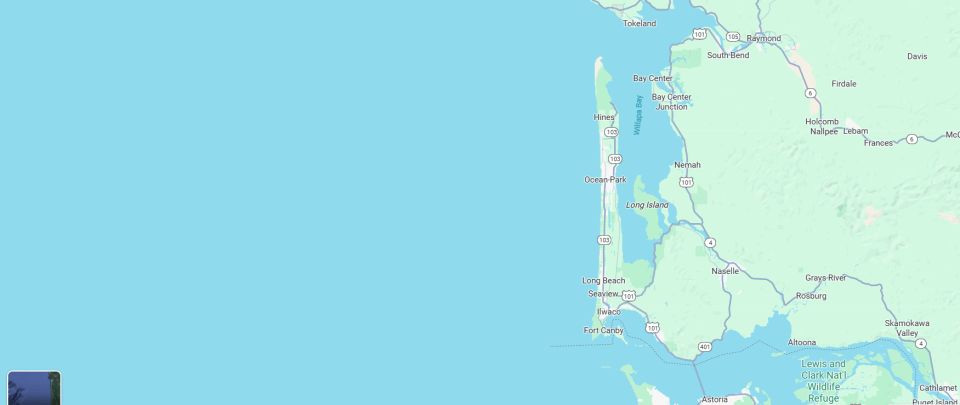

The neighborhood, thanks to Google Maps;

Oysterville is about 2/3 of the way up the Long Beach Peninsula

Why am I talking about a strange-looking, probably Indigenous word or words?

On Sydney of Oysterville’s great little blog, I noticed the author shared a photo 15 years ago from the family’s property in one of the oldest towns in Washington state, Oysterville in the extreme southwest:

Sydney of Oysterville wrote this about it, generously showing us some local oral history:

The sign on the porch above our gate has been there as long as I can remember. It says “TSAKO-TE-HASH-EETL” and means “place of the red-topped grass.” [My emphasis — DDR.] It is what the Chinook Indians called this area because in the summer, beginning about now, the seed heads on the native grasses turn red.

I’ve never thought of tsako-te-hash-eetl as a house name, although I’ve heard visitors refer to the house that way. As I understand it, they are the words Old Klickeas used to describe this northeastern shore of the peninsula to my great-grandfather, R.H. Espy, in the fall of 1853. It’s a place name, not a house name.

Tourists often want to know how to pronounce it (pretty much like it looks) and ask, “exactly what language is it, anyway? Japanese? Finnish?”

“Chinook Jargon,” I tell them. At least, I’ve always thought that because I’ve been told Espy was fluent in the Jargon; I’ve never heard that he knew the actual Chinook language. Of course, the Jargon was a spoken, not a written language, so the words on our sign must be an approximation only. One of my friends who was trying to learn the Jargon told me he didn’t believe I was right about those words; he couldn’t find anything similar in Edward Harper Thomas’s Chinook: A History and Dictionary.

Another friend working toward her PhD in biology at the University of Washington picked samples of all the red-topped grasses in our meadow in front of the house. She identified three different kinds but said none of them were “native.” She said they are all “introduced” species. Hmmm. Foiled again!

Nevertheless, I’m sticking to the explanation that my mother, my aunt, and my uncles always gave about the sign and its meaning. Throughout my lifetime it has defined this place in a very special way. And that’s good enough for me.

I love hearing all of that; thank you, Sydney!

As regards the idea of tsako-te-hahsh-eetl being Chinuk Wawa, that’s very easy to answer. Our strong community of speakers and learners would immediately recognize and understand the words, if it was Jargon. Tsako comes close to Chinook Jargon’s “chako”, ‘to come (here)’, but none of the rest of the phrase makes any sense as CJ. So nope.

And I’ll have to ask you to trust me that it’s also not from Lower Chinookan. I’m not yet fluent in that language, but the expression as it’s quoted to us fails to resemble how things are structured in it.

Which, out of any possibilities that are likely, leaves us Lower Chehalis Salish, the other language of Shoalwater Bay. It would seem, if “Old Klickeas” was the source of the name, that he was one of the Lower Chehalis speakers who lived there. (This gets me wanting to decipher his name, too, but that needs to be deferred.)

Another relevant blog, by the Ocean Park Area Chamber of Commerce, does us the service of reporting that the name has also been said to mean “the home of the yellowhammer”. Aha.

In fact, my research data show that in ɬəw̓ál̓məš, the locality of Oysterville is traditionally called c̓ə́y̓əqʷ, ‘flicker / woodpecker / yellowhammer’ — all 3 are common names used by folks around here for that bird.

That place name has also been mistakenly, but understandably, reported as meaning ‘red’. The actual Lower Chehalis word for ‘red’ is the similar-sounding c̓íq.

So the tsako part of our mystery phrase, when you realize it stands phonetically for [tseyko], = c̓ə́y̓əqʷ ‘flicker’. (That’s what I myself call that bird when I see it around my neighborhood.)

The rest of the phrase kind of snaps into focus after that, if you know some Lower Chehalis.

- The te part = ti in ɬəw̓ál̓məš. You can think of that as an article, like “the”.

- The hahsh part = x̣áš, ‘house’.

- And that eetl seems to represent the Lower Chehalis possessive suffix -čəɬ, ‘our’.

- (Otherwise it’s an unusually garbled -(ə)s, ‘his/her/its’.)

All of that together is a perfectly fluent Lower Chehalis Salish expression, ‘Flicker, our home’, i.e. ‘Oysterville, our home’.

(Otherwise ‘Flicker’s home’, i.e. ‘the home of Flicker’.)

One thing I’ve found interesting is that, being just about the longest-“Settled” area of Washington, Shoalwater Bay has a linguistic history in which White folks reached an unusually high degree of understanding what Indigenous folks were saying.

Rarely do we find anywhere else that the Drifter newcomers were able to pretty accurately remember and write down Native people’s words. I’ve seen a number of similar examples from Shoalwater, though. James G Swan is one of our great early sources for Lower Chehalis (and Chinuk Wawa) data.

A last point — I’ve not yet found out what source people got this Tsako-te-hahsh-eetl information from. Yes, it’s partly family folklore, but where did it originally get written down, such that locals all cite it in the same spelling?

I wouldn’t be surprised if the source for this was Myrtle Johnson Woodcock (1889-1973), a Chinook/Quinault woman who was the so-called “Princess of Oysterville.” She spoke both CW and a bit of other nearby languages. She was one of the nearby Indigenous cultural mediators who provided accurate information on history and culture to local settler society, through both public presentations and her own publications. As an Indigenous poet, whose poetry was often based on information from oral histories with elders, she self-published the first poetry chapbooks by an Indigenous person in the PNW in the 1920s (noting the exception of Pauline Johnson, of course). She also was instrumental in the longstanding and ongoing struggle for the Chinook to gain federal recognition. I will keep this phrase in mind when looking back through her work, and the many newspaper articles about her. I’m sure many fellow readers have encountered her language presentation online, recorded in 1952. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nBy8fY06TdA As always, thanks for new entry!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really good thoughts, thank you much for posting them to share here, Robert!

LikeLike