Lempfrit’s legendary, long-lost legacy (Part 26A: the Credo continued)

More excellent material for us to learn from.

Page 1 of the 26th pair of pages (mis-numbered as “25” on the original page) from this precious document again brings us plenty of stuff worth knowing about Chinook Jargon — this time moving from lists of words into texts.

(Here’s a link to the other posts in this mini-series.)

“[SIC]” shows that someone mis-wrote a word. It wasn’t necessarily Lempfrit, since he was copying from someone else’s manuscript, Modeste Demers’ now-lost original to be exact.

For today’s installment, Alphonse Pinart’s “Anonymous 1849” copy (read it for free online) lacks any pages that correspond to what we’re seeing from Lempfrit.

Where you see [le]tters in square brackets, they’re not visible on the page copy that I’m working from, but we infer that they really are there!

By the way, the notation ___ means that the preceding entry is repeated in that position, along with some additional word(s).

See if you recognize words in these unusual spellings! I think we have a couple more small discoveries today, again showing the value of examining every Chinuk Wawa document — even those that appear to be straight copies of each other!

Beginning with today’s textual materials, we have the rewarding experience of seeing how a French-speaker (in the pre-Anthropology era, no less) conceptualized the word-to-word flow of spoken Jargon. Lempfrit’s “glosses” of each Chinook Jargon word might be pretty different from how you think of each word’s meaning!

If you need some quick proof that Chinook Jargon is an Indigenous language, take a look at how different Lempfrit’s French, and the conventional English lines, are from what the Jargon here is literally — and fluently — saying.

When I say that this Chinuk Wawa is fluent, I’m saying that it’s totally characteristic stuff from what I’ve now come to call the Central Dialect. That’s the oldest variety of the language, the early-creolized Jargon associated with Fort Astoria and Fort Vancouver. The document we’re looking at here was created before the Northern or Southern dialects (associated with British Columbia and with Oregon’s Grand Ronde Reservation, respectively) even existed.

Today’s installment is the continuation of the “Credo“, i.e.:

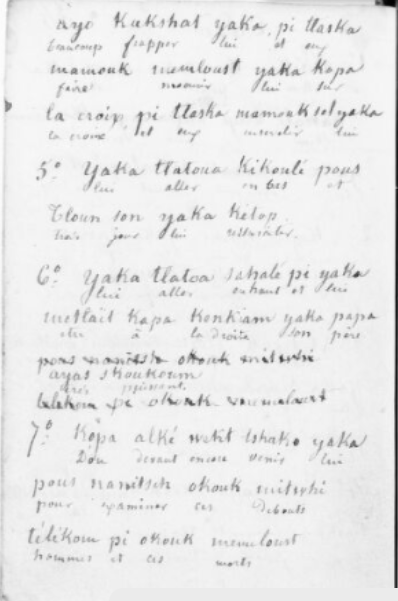

(…) ayo kakshat yaka, pi tlaska

(…) beaucoup frapper lui et eux

‘(…) thrashed him, and they’mamouk memloust yaka kopa

faire mourir lui sur

‘killed him on’la croix, pi tlaska mamouk sel yaka

la croix et eux ensevalir lui

‘a cross, and they wrapped him (his body) up.’5o Yaka tlatoua kikoulé[;] pous

lui aller en bas et

‘He went under; when it was the’tloun son yaka kétop.

trois jour lui ressusciter.

‘third day he got up.’6o Yaka tlatoa [Ø] sahalé pi yaka

lui aller en haut et lui

‘He went up (to heaven) and he’mitlait kapa kenkiam yaka papa

être à la droite son père

‘is at the right (of) his father’

pous nanitsh okouk mitwhi

‘to see the standing’ayas skoukoum

très puissant.

‘who is very powerful.’

telekom pi okouk memaloust

‘people and the dead ones.’7o Kopa alké weh̃t tshako yaka

D’où devant encore venir lui

‘In [SIC] eventually he will come again’pous nanitsch okouk mitwhi

pour examiner ces debouts

‘to visit the standing people’télékom pi okouk memaloust

hommes et ces morts

‘and the dead ones.’

Once again, that’s OK Chinook Jargon, but not wonderful, and in places it’s definitely not good grammar.

Here’s a traditional English-language rendition of the relevant passage:

…He descended to the dead. On the third day he rose again. He ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again to judge the living and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting. Amen.