Nater 2025 on foreign influences in Nuxalk (Bella Coola Salish)

I’ve just been in Chilliwack, BC, at the 60th ICSNL (International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages), which led to my becoming aware of a new study that discusses Chinook Jargon.

Linguist Hank Nater contributed 2 papers for the conference. I want to focus on his “Jargon and European Origins of some Bella Coola Lexicon“. That’s the language also known as Nuxalk.

Per Nater, “less than a third of all Bella Coola verbo-nominal vocabulary is of Salish” origin, although Nuxalk is a Salish language.

His paper argues that some of Nuxalk’s lexicon is from the foreign languages Chinuk Wawa, Russian, and Spanish. From the outset, I have comments on Nater’s interpretation of Pacific Northwest language history.

(Below, BeCo = Bella Coola, i.e. Nuxalk)

Nater’s paper begins with this:

Below, I consider BeCo copies of Chinook Jargon words (4.1), one word of Russian origin (4.2),

and one word that owes its existence to Spanish traders (4.3). All words were copied in the early

nineteenth century, when the fur trade peaked, and BeCo traders did business in C’aamas [footnote] (now called Victoria) on Vancouver Island.[footnote:] Cf. Makah c’a·bap, No c’a·maqak ‘sound, large body of water’ (from √c’a).

About that: I myself suggest that Nuxalks did their business in Victoria after that town was established, in 1843 and later — thus not “the early nineteenth century”.

And much of their business there would’ve been non-fur-trade-related; as time went on, Indigenous people primarily came to Biktoli/Metuliya in order to work. Industries they engaged in included fish canneries and so forth.

Now, about Nater’s Footnote 2 there: I’m grateful for his suggestions about a new etymology of the Indigenous name of Victoria, c’aamas.

- But for what it’s worth, I’ve been told by a Kwakwaka’wakw elder that the name means (as I remember her words) ‘lots of pointy things’, which she said referred to the spires of churches and such in the town. ‘Church’ in the [Wakashan-family] Kwaka’ala language(s) is in fact c’am-ac’i.

- The place name is also used in some Coast Salish-family languages of the area (it’s their traditional territory), where maybe it has a similar literal meaning. (Aert Kuipers “Salish Etymological Dictionary” 2002:30 has Proto-Salish *c’am ‘sharp pointed’.)

- And by some First Nations, Vancouver is called by the same name, e.g. in the Sm’algyax language -Tsimshianic family].

Nater goes on to give a valuable list, from his own field notes, of some Chinook Jargon words that historically got taken into Nuxalk. It merits further comment, to increase its usefulness, so I’ll be adding notes.

Up front, let me tell you that Chinook Jargon tulu is truly widespread in Northwest Coast languages, including Kwakw’ala.

And Nater is 100% right, in my view, in reasoning that words like ‘apples’ ‘oranges’, and ‘turnips’ came to these languages via CJ; I’ve often commented that the old-time published Chinook dictionaries economized by leaving out words easily recognizable to Settler readers as being English.

OK, now:

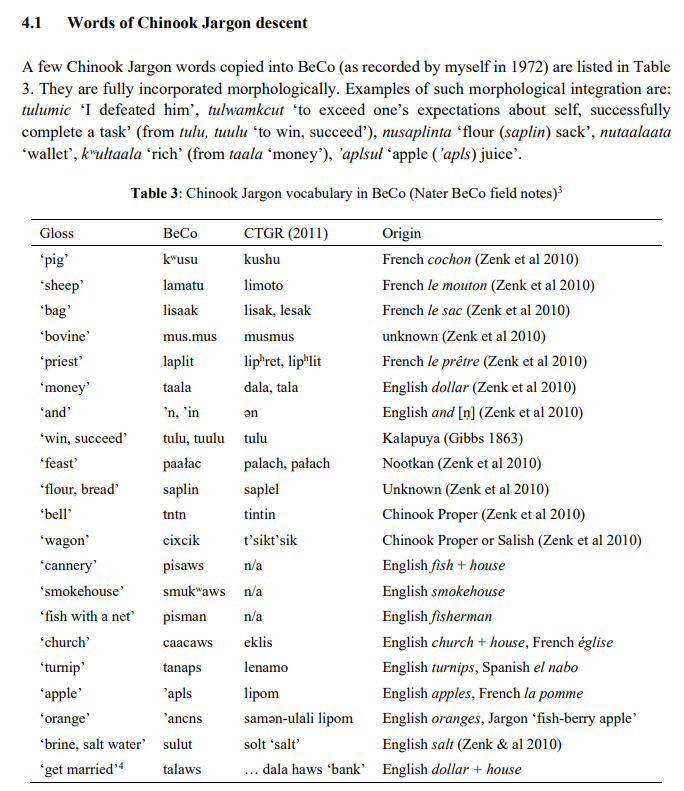

4.1 Words of Chinook Jargon descent

A few Chinook Jargon words copied into BeCo (as recorded by myself in 1972) are listed in Table 3. They are fully incorporated morphologically. Examples of such morphological integration are:

tulumic ‘I defeated him’, tulwamkcut ‘to exceed one’s expectations about self, successfully complete a task’ (from tulu, tuulu ‘to win, succeed’), nusaplinta ‘flour (saplin) sack’, nutaalaata ‘wallet’, kʷultaala ‘rich’ (from taala ‘money’), ‘aplsul ‘apple (‘apls) juice’ [DDR: the apostrophe seems to stand for a glottal stop there].Table 3: Chinook Jargon vocabulary in BeCo (Nater BeCo field notes) [footnote 3]

Gloss BeCo CTGR (2011) Origin

‘pig’ kʷusu kushu French cochon (Zenk et al 2010)

‘sheep’ lamatu limoto French le mouton (Zenk et al 2010)

ʻbag’ lisaak lisak, lesak French le sac (Zenk et al 2010)

‘bovine’ mus.mus musmus unknown (Zenk et al 2010) [A]

‘priest’ laplit lipʰret, lipʰlit French le prêtre

‘money’ taala dala, tala English dollar (Zenk et al 2010)

‘and’ ‘n,’in ən English and [n] (Zenk et al 2010) [B]

‘win, succeed’ tulu, tuulu tulu Kalapuya (Gibbs 1863)

‘feast’ paaɬac palach, paɬach Nootkan (Zenk et al 2010)

‘flour, bread’ saplin saplel Unknown (Zenk et al 2010)

ʻbellʼ tntn tintin Chinook Proper (Zenk et al 2010)

‘wagon’ cixcik t’sikt’sik Chinook Proper or Salish (Zenk et al 2010)

‘cannery’ pisaws n/a English fish + house [C]

‘smokehouse’ smukʷaws n/a English smokehouse [D]

‘fish with a net’ pisman n/a English fisherman [E]

‘church’ caacaws eklis English church + house [F], French église

‘turnip’ tanaps lenamo English turnips, Spanish el nabo [G]

‘apple’ ‘apls lipom English apples, French la pomme

‘orange’ ‘ancns samən-ulali lipom English oranges, Jargon ‘fish-berry apple’ [H]

‘brine, salt water’ sulut solt ‘salt’ English salt (Zenk & al 2010) [I]

‘get married’ [footnote 4] talaws …dala haws ‘bank’ English dollar + house [J] ‘

3 Here and henceforth, CTGR stands for Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon.

4 The original meaning must have been ‘to (go to the) bank: deposit or withdraw money for a dowry or wedding feast’.

MY FOOTNOTES ON THE ABOVE

[A] Nater goes on to discuss the known possible etymologies of this word, FYI.

[B] I have to point out that this word isn’t known throughout Chinook Jargon dialects; it’s only been documented sporadically in both Southern & Northern CJ.

[C] I’ve previously suggested that “fish-house” was an established phrase in Northern Chinook Jargon, and I’d add that both components of it are already basic vocabulary items throughout CJ. Just this week I witnessed a Gitksan elder use this phrase at the Salish Conference, commenting negatively on “using this English in the fish-house“, seemingly meaning a longhouse. (See note [D].)

[D] I’ve also suggested “smoke-house” as a known Northern CJ phrase for the traditional Indigenous longhouses.

[E] This phrase can be taken as from CJ pish+man / fish+man instead of from English fisherman. There’s a pattern of Chinook Jargon compound nouns getting taken into NW Coast languages.

[F] I’ve previously noticed that church+house is probably another hitherto undocumented regional NW Coast CJ phrase. It’s a place name in the territory of the ʔayʔajuθəm-speaking Salish people, for instance. It’s a word in the Haíɫzaqvḷa language. In Sm’algyax they say wap dzots, which is ‘house (of the) church’, where dzots is the local pronunciation of the English/Jargon loan-word church. I also see the word church being used in Massett Haida.

[G] This ‘turnip’ word is really from Canadian/Métis French le(s) navot(s). There are virtually no Spanish words in Chinook Jargon.

[H] This ‘fish-berry-apple’ compound is actually a neologism at Grand Ronde in Oregon, within the last 20 years; it wouldn’t have been used or known in Nuxalk land.

[I] Given Nater’s gloss, I would want to check whether there’s any native Salish root for ‘salt(y)’ and ‘water’ in this word. There are similar-shaped forms throughout the Salish language family.

[J] I have further, skeptical questions about this supposed connection of ‘bank’ and ‘marriage’…tell me more about Nuxalk culture, somebody.

Other points

Nater goes on to speculate on Nuxalk’s word panya ‘to smoke fish’ being from a Russian bánya ‘sauna’. Nope, I say. There’s no good evidence for any Nuxalk-Russian contact, nor for any motivation for Nuxalks to borrow a European word for an Indigenous practice, nor for borrowing a noun to express a verbal concept in this case. Instead I think we can keep looking for Indigenous-based analyses.

And Nater’s reasoning for thinking Nuxalk ‘yanahu ‘turnip’ is from Spanish el nabo doesn’t follow tried and true historical linguistic reasoning. Much more likely to me than this being more or less the only Spanish loan into NW Coast languages is that it’s just one more Chinuk Wawa item among the considerable number that were taken into the region’s languages, and phonologically mutated there.

The strongest claim we need make about the original French /l/ having become /y/ is that this is an already known sound shift in the region, for example in the Salish languages Comox, Sliammon, Squamish, Songish, Klallam, and Thompson (per Aert Kuipers 2002:3), and implicit in the ethnic-group name “Yuculta / Euclataw” and other y-type spellings of it, a.k.a. the Liǧʷiłdaxʷ branch of the Wakashan language Kwak’wala.

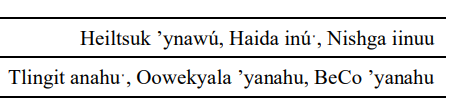

Here’s the relevant section of his Table 4 showing the resulting shapes of this word in various NWC languages:

Heiltsuk ‘ynawú, Haida inú•, Nishga iinuu

Tlingit anahu•, Oowekyala ‘yanahu, BeCo ‘yanahu

Well now,

Hi Dave,

This is grand stuff!

I wonder if we (you), should look into the source of both Spanish and Russian (bearing in mind the various dialects therein), and see what else can be explained in the way of anomalous words in Coastal and Interior languages.

I’m still obsessed with determining the origins of place names here on the Plateau and possibly finding out what was a direct translation of local names into CJ and/or michif, or Great Lakes trade lingos, depending on who was called upon to provide a name for a place to the men of the post, or outfit.

Your thoughts?

J.

LikeLike

In re Bella Coola panya < Russian banya, you didn’t pay full attention:

BeCo panya (transitive-intransitive) ‘to smoke fish’ has no Salish cognates or areal matches, but

note that:

it bears a striking phonetic resemblance to Russian баня [baɲə] ‘sauna’;

due to restricted means of communication as well as similarities between banyas and

smoke-houses, either structure – as a vapor-emitting shed or cabin that is quite dissimilar

to the average traditional dome-shaped sweat lodge – could easily be misidentified by

visitors during discussions;

BeCo transitivity-intransitivity is often indicative of an originally nominal status, such that

X may gloss as ‘to apply (an) X to something’, see Nater (1983);

panya is clearly a redundant (and once-fashionable) lexical innovation, as BeCo already

had q’ʷup (tr.) ‘to (expose to) smoke’. If not for contact with Russian traders, a BeCo

smokehouse might now have been called *nusq’ʷupalsta or *nusuq’ʷpalsta rather than

nuspanyaasta.

This word must have entered the language in the early 19th century (some twenty years after

Mackenzie set foot in BeCo, see Mackenzie 1801 and Nater 2020), when the fur trade boomed, and

Chinook Jargon began to flourish. In regards to the second argument, note that Chinook Jargon had

one word for both ‘smoke’ and ‘steam’ at the time (Hibben 1889 and Shaw 1909), which could

certainly lead to misconstruction in conversations between Russian and BeCo traders whenever,

and wherever, their paths crossed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Howdy, Henk, I’ve wished I could cross paths with you at the Salish Conferences; I think we would have really excellent conversations. Apparently we share a background in Slavic linguistics with some other Salishanists such as Ewa Czaykowska-Higgins!

I’ve long attempted (with little success) to get hold of your work on Nuxalk, particularly any dictionary as that’s been a rare tool to find for that language.

I’m flattered to receive your responses to my thoughts about this 2025 paper of yours, naika wawa masi!

I would be grateful for any known documentation of Russian-Nuxalk contact.

Do you happen to know Dale McCreery in Bella Coola, I wonder?

– – – Dave Robertson

LikeLike