AF Chamberlain’s field notes of Chinuk Wawa from SE British Columbia (part 15) = last installment

New discoveries!Plus, confirmation of stuff we’ve found elsewhere in the Northern Dialect of Chinook Jargon!

Chamberlain’s “c” is the “sh” sound, and his “tc” is the “ch” sound. His “ä” is the “a” in “cat”, a frequent sound in the Northern Dialect.

I’ve tried to show paragraph breaks, below, where I think Chamberlain was trying to place them.

I really appreciate Chamberlain’s noticing which words and phrases are newer in Northern Chinook Jargon, an observation that independently 100% corroborates my own based on separate data from the same time period in other regions of British Columbia.

I’d add that the presence of the pronunciation [ä] in words tracing to English seems to show renewed English-language influence on old, established Jargon words such as sámən, which had lacked that sound before.

(A link to all installments in this mini-series)

-

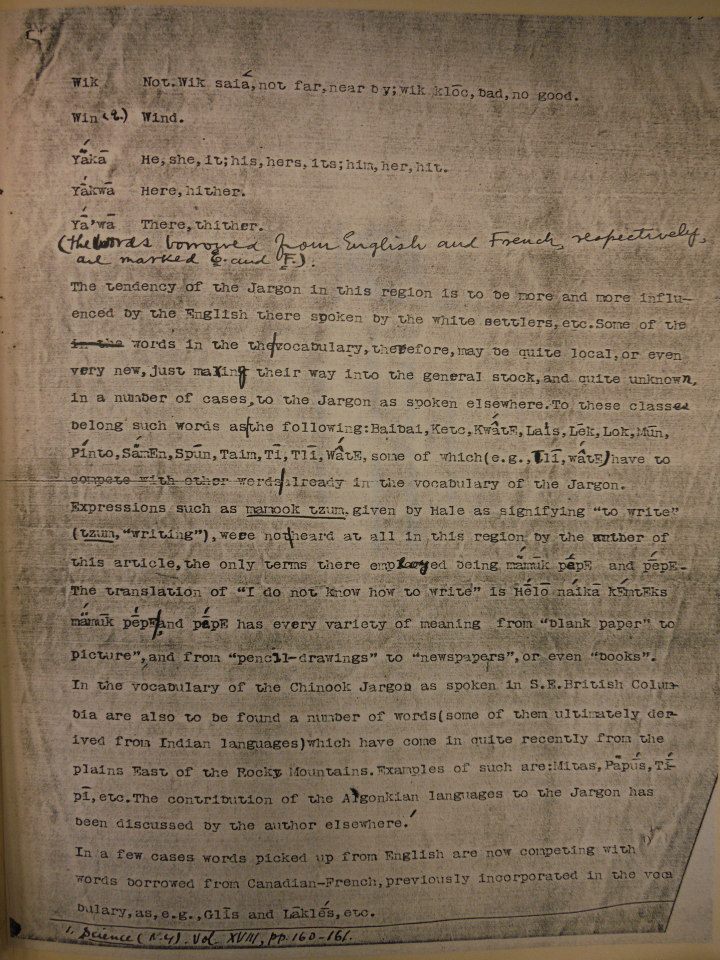

wik ‘not’

- wik saia ‘not far, near by’ [DDR note: he only gives this literal meaning for the phrase, but not the common metaphorical ‘almost’.]

- wik klōc ‘bad, no good’ [DDR: this expression is another of the very few instances where the Northern Dialect preserves the negator wik, which is bumped aside by hḗlō , as Chamberlain spells it, 99% of the time.]

-

win (E[nglish]) ‘wind’

-

yä́kā ‘he, she, it; his, hers, its’ him, her, hit [i.e. ‘it’]‘ [DDR: it seems weird for Chamberlain to indicate a long vowel in the unstressed final syllable, a pronunciation we haven’t heard in any dialect. Contrast this with the next two words, where the final syllable really is normally long.]

-

yā́kwā ‘here, hither’

-

yā́‘wā ‘there, thither’

(The words borrowed from English and French, respectively, are marked E. and F.)

The tendency of the Jargon in this region is to be more and more influenced by the English there spoken by the white settlers, etc. Some of the words in the vocabulary, therefore, may be quite local, or even very new, just making their way into the general stock, and quite unknown, in a number of cases, to the Jargon as spoken elsewhere. To these classes belong such words as the following: baibai, ketc, kwấtE, lais, lék, lok, mūn, pínto, sä́mEn, spūn, taim, tī, tlī, wấtE, some of which (e.g., tlī, wấtE) have to compete with other words already in the vocabulary of the Jargon.

Expressions such as mamook tzum, given by Hale as signifying “to write” (tzum, “writing”), were not heard at all in this region by the author of this article, the only terms there employed being mä́mūk pḗpE and pḗpE. The translation of “I do not know how to write” is Hḗlō náika kÉmtEks mä́mūk pḗpE, and pḗpE has every variety of meaning from “blank paper” to “picture”, and from “pencil-drawings” to “newspapers”, or even “books”.

In the vocabulary of the Chinook Jargon as spoken in S.E. British Columbia are also to be found a number of words (some of them ultimately derived from Indian languages) which have come in quite recently from the plains East of the Rocky Mountains. Examples of such are mitas, päpū́s, tī́pī, etc. The contribution of the Algonkian [Algonquian] languages to the Jargon has been discussed by the author elsewhere.[1]

In a few cases words picked up from English are now competing with words borrowed from Canadian-French, previously incorporated in the vocabulary, as, e.g. glīs and laklḗs, etc.

[1] Science (N.* 4*), Vol. XVIII, pp. 260-261 [1891]. [DDR: see my post about that article.]

That’s the conclusion of our mini-series on this wonderful manuscript vocabulary from Alexander Francis Chamberlain. There’s lots to learn from it, especially for speakers of Northern Chinook Jargon!