1899: Jargon speech by Rinehart for a stolen totem pole

One of the very few examples we have of someone talking about totem poles in Chinuk Wawa…!

This “Speech of Acceptance” of the Alaska Totem Pole in Pioneer Place comes from someone with long experience of talking Oregon-style Chinook Jargon — albeit from southern and eastern peripheral areas — so I take a strong interest in seeing how he makes sentences.

His pronunciation “di-rate” brings to mind Grand Ronde’s dret, for the word you might otherwise know as delate ‘really; straight’.

This speech is accompanied by an English translation, since this was after the frontier period when most folks could be expected to know the Jargon well.

I’ll compare the provided translation with what I understand the speech to be saying…my translation will be marked DDR. The differences are interesting! One tipoff is that the English translation is “flowery”…Note, too, that by 1899 non-Natives were a strong majority in the Pacific Northwest. Most Settlers who could speak Jargon at that time spoke it more with each other than with Indigenous people. This single fact powerfully explains the quirks that we consistently find from “White” speakers of Chinuk Wawa in the late- and post-frontier eras.

As always, I’m giving the most charitable possible translation to the speaker’s Chinook Jargon, that is, I assume they were making sense. (Until I can no longer make sense of a given expression.)

SPEECH OF ACCEPTANCE.

Mr. Rinehart’s Appropriate Introductory Remarks in Chinook.

In accepting the pole on behalf of the city, President Rinehart said:

“Klosh Til-a-Kum (laughter): Ni-ka Sah-a-la til-kum di-rate wa-wa. Skoo-kum wa-wa. Klosh tum-tum mes-si-ka. Kon-a-way Si-wash, kon-a-way Boston til-a-kums cha-co pee nan-ich To-tem-pole mit-lite ya-wah. Si-ah Bostons cha-co ko-pa Seattle, nan-ich. In-i-ti- Skoo-kum-chuck cha-co pee nan-ich. Spose kul-tus nan-ich di-rate wawa: ‘Ahn-cut-ty si-wash ma-mook. Kul-tus pot-latch ma-mook, pee Boston kap-swal-la.’ Si-wash wa-wa ka-kwa. ‘Kon-a-way mow-ich klat-a-wa Skoo-kum Ty-ee Se-alth mem-a-loose. Klosh klooch-man-Angeline klat-a-wa. To-tem pole mit-lite, mit-lite. Sah-ah-le Seattle is-kum Sas-ah-le To-tem-pole. Nah-wit-ka, six.” (Applause.)

“Mr. Chairman, my vocabulary is limited. I cannot soar among the eagles. Let me resume the ‘White Man’s Burden.’ Even after forty-five years of border life, most of which has been spent among the red men whom this rude monument is designed to commemorate, I have not the courage to attempt a fitting reply to the eloquent address of the gentleman through whom you have made this presentation. Indeed, it was not expected of me, I am sure; for it is not too much to say that, in oratory, the gifted author of ‘High Tide at Gettysburg’ towers above as the Washington monument at our national capitol towers above this grotesque specimen of aboriginal art. (Applause.)

“Permit me, therefore, thus briefly, on behalf of the city council and in the name of the city of Seattle, to accept this generous gift, and to thank you, gentlemen of the committee, and through you we desire to thank the donors who brought us this trophy out of the frozen North, from the far-off land of the midnight sun.

“It has been hinted by the knowing ones that the excursionists were prompted to this generous act by a keen sense of grotesque humor, intending it as a ‘monumental joke’ on the city council and on the Indians from whom this trophy was captured. To all such I would say: ‘Go thou and do likewise. We are ready to accept more such.’ Gentlemen, again I thank you.” (Profound applause.)

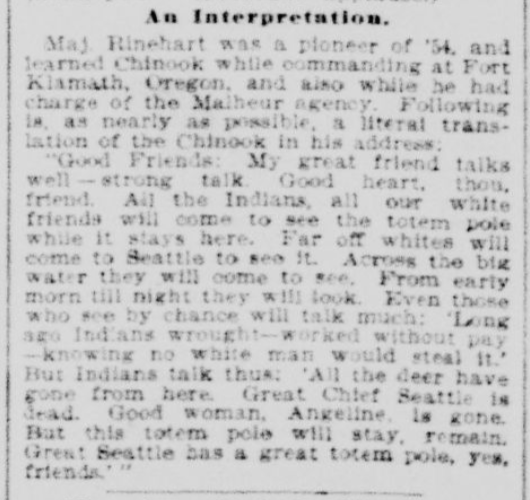

An Interpretation.

Maj. Rinehart was a pioneer of ’54, and learned Chinook while commanding at Fort Klamath, Oregon, and also while he had charge of the Malheur agency. Following it as nearly as possible, a literal translation of the Chinook in his address:

“Good Friends: My great friend talks well — strong talk. Good heart, thou, friend. All the Indians, all our white friends will come to see the totem pole while it stays here. Far off whites will come to Seattle to see it. Across the big water they will come to see. From early morn till night they will look. Even those who see by chance will talk much: ‘Long ago Indians wrought — worked without pay — knowing no white man would steal it.’ But Indians talk thus; ‘All the deer have gone from here. Great Chief Seattle is dead. Good woman, Angeline, is gone. But the totem pole will stay, remain. Great Seattle has a great totem pole, yes, friends.’ “

— from the Seattle (WA) Post-Intelligencer of October 19, 1899, page 2, column 5

Now, to analyze the speech:

Klosh Til-a-Kum (laughter): Ni-ka Sah-a-la til-kum di-rate wa-wa. Skoo-kum wa-wa.

ɬúsh tílixam: [1] nayka sáx̣ali [2] tílixam drét wáwa — skúkum wáwa. [3]

DDR: ‘Good people/friends: my tall/high friend talks straight — shouting.’

‘Good Friends: My great friend talks well — strong talk.’

Klosh tum-tum mes-si-ka.

ɬúsh tə́mtəm msayka. [4]

DDR: ‘You folks are happy.’

‘Good heart, thou, friend.’

Kon-a-way Si-wash, kon-a-way Boston til-a-kums cha-co pee nan-ich To-tem-pole mit-lite ya-wah.

kʰánawi sáwásh, kʰánawi bástən-tílixam-s cháku pi nánich tʰótəm*-pʰól* míɬayt yá(k)wá.

DDR: ‘All the Native people, all the White people come and see the totem pole that’s (t)here.’

‘All the Indians, all our white friends will come to see the totem pole while it stays here.’

Si-ah Bostons cha-co ko-pa Seattle, nan-ich.

sáyá bástən-s cháku kʰupa siyætl*, nánich Ø(,) [5]

DDR: ‘White people come from far away to Seattle, to see it(,)’

‘Far off whites will come to Seattle to see it.’

In-i-ti- Skoo-kum-chuck cha-co pee nan-ich.

ínatay skúkum chə́qw(,) [6] cháku pi nánich Ø.

DDR: ‘across the mighty waters(,) coming and seeing it.’

‘Across the big water they will come to see.’

Spose kul-tus nan-ich di-rate wawa:

spos kʰə́ltəs-nánich(,) drét wáwa: [7]

DDR: ‘If just having a glance(,) really saying:’

‘Even those who see by chance will talk much:’

{Orphan sentence:} ‘From early morn till night they will look.’

‘Ahn-cut-ty si-wash ma-mook. Kul-tus pot-latch ma-mook, pee Boston kap-swal-la.’

ánqati sáwásh mámuk Ø, kʰə́ltəs-pátlach-mámuk [8] Ø, pi bástən kápshwála Ø.

DDR: ‘The long-ago Native people made it, making it as a gift*, but the Whites stole it.’

‘Long ago Indians wrought — worked without pay — knowing no white man would steal it.’

Si-wash wa-wa ka-kwa.

sáwásh wáwa kákwa(:)

DDR: ‘This is what the Natives say(:)’

‘But Indians talk thus;’

‘Kon-a-way mow-ich klat-a-wa(.)

kʰánawi máwich ɬátwa. [9]

DDR: ‘The deer have all gone.’

‘All the deer have gone from here.’

Skoo-kum Ty-ee Se-alth mem-a-loose.

skúkum [10] táyí siʔáɬ míməlus.

DDR: ‘The powerful chief Seattle is dead.’

‘Great Chief Seattle is dead.’

Klosh klooch-man-Angeline klat-a-wa.

ɬúsh ɬúchmən ǽndjəlayn* ɬátwa.

DDR: ‘The good woman Angeline has gone.’

‘Good woman, Angeline, is gone.’

To-tem pole mit-lite, mit-lite.

tʰótəm*-pʰól* míɬayt, Ø míɬayt.

DDR: ‘The totem pole stays, it stays.’

‘But the totem pole will stay, remain.’

Sah-ah-le Seattle is-kum Sas-ah-le To-tem-pole. Nah-wit-ka, six.” (Applause.)

sáx̣ali siʔáɬ ískam [11] sáx̣ali tʰótəm*-pʰól*(,) nawítka, síks. [12]

DDR: ‘High/tall Seattle has fetched a totem pole, yes, friends.’

‘Great Seattle has a great totem pole, yes, friends.’

The notes:

[1] tílixam: This word was the normal way to express ‘friend(s)’ in the Northern Dialect, therefore in Seattle at the time of this speech. Back when Rinehart had learned & used Chinook Jargon, it meant ‘people’. He seems to be accommodating his audience of Settlers here. See also the last footnote, below.

[2] nayka sáx̣ali tílixam: Throughout the speech Rinehart keeps using sáx̣ali (‘high; tall’) in a way that only a Settler would, to mean ‘great; illustrious’. This seems to hinge on an English-language metaphor of ‘elevated’ for ‘respected’.

[3] skúkum wáwa: This is typical Settler talk, and to some extent Northern Dialect; skukum (‘strong’) is another word that Settlers came to use in a meaning ‘excellent’. Previously, in the Southern Dialect, skukum wawa meant ‘shouting’!

[4] msayka: It’s possible that here Rinehart actually mean the singular ‘you’, mayka. Many Settlers confused the singular and plural 2nd person pronouns.

[5] nánich Ø: Rinehart shows us a number of times that he uses the Chinuk Wawa “silent IT” pronoun correctly.

[6] skúkum chə́qw: Characteristic of Settler talk, Rinehart here calls the ocean the ‘powerful water’ (or, if you read footnote 3, ‘great water’). This same phrase, though, is established in the meaning of ‘a rapids’ in a river.

[7] spos kʰə́ltəs-nánich(,) drét wáwa: A number of times, Rinehart forms clauses without subjects, which I’m forced to take as sort of “-ing” participles to read them as being grammatical. This is much more a Settler habit than of speakers who used the language more frequently.

[8] kʰə́ltəs-pátlach-mámuk: This is a newly coined expression, not known from other speakers. It seems to be influenced by English, ‘doing something for free’. (The existing phrase kʰə́ltəs-pátlach was already well established as ‘a gift’.)

[9] kʰánawi máwich ɬátwa: This is heavily English-influenced Settler talk, a literal translation from the English phrase. The normal, long established way to say something is ‘all gone’, i.e. there’s no more of it, is hilu, so Rinehart could’ve just said mawich hilu or hilu mawich. This expression kʰánawi máwich ɬátwa really means ‘all of the deer have left’ in Jargon.

[10] skúkum táyí siʔáɬ: Again with the use of skukum ‘strong’ to mean ‘great; excellent’, a Settler habit in Chinuk Wawa.

[11] siʔáɬ ískam sáx̣ali tʰótəm*-pʰól*: This is another thing Settlers habitually did in the Jargon, confusing the various words for ‘getting’ — presumably because English uses just the one word for so many different functions. The word iskam means ‘to fetch; to (go) get on purpose’, which I don’t believe is the intended meaning of Rinehart. More appropriate here would be t’ɬap ‘receive; happen to get’.

[12] nawítka, síks: Here, Rinehart uses the older / Southern Dialect word for ‘friend’. Compare footnote 1. This synonym siks was well known among Settlers, but my research in the Northern Dialect shows that the English number-word ‘6‘ (siks) was so common that it crowded out the identical-sounding word for ‘friend’.

My overall evaluation of Rinehart’s Chinook Jargon —

- he was definitely a fluent speaker;

- he was probably a bit rusty at it, as were most Settlers in 1899 because they were the majority and no longer had to accommodate other folks’ language needs;

- he spoke it in ways that reflect talking with other Settlers;

- and he was trying to do some creative writing in it, which rarely ends well.

Bonus fact:

I can recommend reading about the totem pole of Pioneer Square. It’s one of the oldest I know of, and one of the few I’ve heard about honoring a woman. And it was definitely stolen.