1897 reminiscence: “The Chehalis River Indian Treaty” that never happened

It’s a mistake to refer to “The Chehalis River Indian Treaty” of 1855, because no such treaty was ever agreed on or signed.

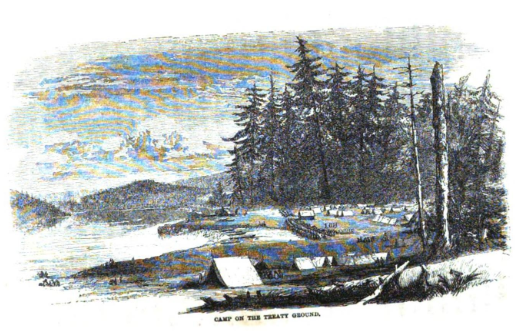

“Camp of the treaty ground” on the Chehalis, between pages 334 & 335 of Swan’s book

James Gilchrist Swan, a Shoalwater Bay settler and one of numerous excellent speakers of Chinuk Wawa at the failed negotiations, tells why the proceedings fell apart. This story occupies pages 327 and following of Swan’s famous 1857 memoir “The Northwest Coast: Or, Three Years’ Residence in Washington Territory“. Here we have a later, abridged telling by him in a newspaper. I refer you to the book (free to read online at that link) for fuller details.

The proceedings were conducted via Chinook Jargon, which, it’s fair to point out, was then at its most fully developed linguistic state (creolized) in precisely these territories of southwestern Washington and the lower Columbia river.

Those who characterize the Jargon as having been “too primitive” to conduct treaty negotiations, due to its Indigenous pidgin origins, are missing a nuanced point in claiming that.

From my perspective as a PhD linguist with 25 years of original and groundbreaking research into CJ, the actual shortcomings of the treaty dealings as actually carried on were that this language, as can equally be said of the local tribal languages, hadn’t yet had enough time to adapt to Euro-American legal concepts, whereas its ability to put across Native values was pretty darn strong.

We don’t so much hear of the US government representatives misunderstanding what “Indians” were telling them in these Stevens (and other) treaty parleys, but we consistently hear how tribal people had many misunderstandings of what was being asked of & promised to them (from the viewpoint of the Whites, at least).

In the instance of the would-be Chehalis treaty, however, the obstacles are crystal clear. Read this article (transcribed by me below these images of it) and see how you understand things.

THE CHEHALIS RIVER INDIAN TREATY

A Reminiscence of 1855.

By JAMES G. SWAN.

In Mr. Meany’s excellent article on “Ten Indian Treaties by Gov. Isaac I. Stevens,” in the Post-Intelligencer of July 14, 1897, mention is made of the attempt to make a treaty with the [Lower] Chehalis, Chinook, Quenaiult and other bands of Coast Indians, which failed through the arrogance of the Chehalis chief, Karkowan, and his son, Tleyuk, who wanted the reservation on his land and induced the chiefs of all the other bands to refuse to sign the treaty, except the Quenaiult tribe, where the reservation was finally made on the lands of that tribe. I was at that time residing at Shoal Water bay, and, during the winter of 1854, I received from Gov. Stevens a letter inviting me to be present at a meeting to be held on February 25, 1855, on the claim of Mr. James Pilkington, who had a clearing on the banks of the Chehalis river, where the town of Montesano now stands.

On February 6 a letter was brought to me from Col. Henry D. Cook [i.e. the “Coch” below?], who was at Grays harbor, superintending the arrangements for the forthcoming meeting, informing me that he would meet me at Armstrong’s, now Hansen’s point, on the south side of the entrance to Grays harbor, on February 24, and convey me up the Chehalis river to the treaty ground. Dr. J. Cooper, who was residing at Capt. Charles Russell’s, making collections for the Smithsonian institution, decided to accompany me, and, while we were making our arrangements to start, Mr. William B. Tappan, the Indian sub-agent for the southwestern section of the [Washington] territory, arrived on his way to the treaty camp with several Chinooks and other Columbia river Indians with him. Old Chief Toke, for whom Toke’s point, on Shoal Water bay was named, with his family and other resident Indians, joined our party and we crossed the bay to Toke’s point on the afternoon of February 23, and passed the night at the house of Mr. J.F. Barrows, the Indians going to Toke’s lodge.

February 24 we started by sunrise for Grays harbor. Dr. Cooper, Agent Tappan and I decided to walk on the beach, as the air was clear and frosty. The Indians went in their canoes around from Shoal Water bay to Grays harbor. After a pleasant walk in the fresh, cold breeze we reached Carcowan’s lodge, near Armstrong’s house, on the point. Here we found Col. Coch and one of Judge Ford’s sons. They had a fine meal prepared for us of juicy roasted baked potatoes, hard bread and coffee, and as soon as we had finished eating we prepared to start, and, having crossed the harbor safely, we entered the Chehalis river just at sundown. The tide was moving out strongly and the Indians decided to camp for the night, so we went ashore, built a big fire, cooked some supper and soon turned in to sleep, and at dawn the next morning we all started. We had been joined during the night by some fifteen or twenty canoes, all filled with men, women and children.

We were about ten miles distant from the treaty ground, but we did not wait for breakfast, but were soon on our way. The Indians did their utmost to see who would reach camp first, so they paddled and screamed, and shouted and laughed, and cut up all sorts of antics which served to keep them in a glow. As we approached the camp we all stopped at a bend in the river a short distance from Pilkington’s claim, and all the natives washed their faces, combed their hair and put on their best clothes. [DDR note: Is this borrowed from the identical practice among the Métis fur-trade employees who had married into PNW Indigenous families?] The women arrayed themselves in their bright, gaudy dresses and shawls, and having rubbed grease on their faces, painted them with vermillion and decked themselves out with their beads and trinkets, and in about ten minutes we were a gay looking crowd. The appearance of the canoes filled with Indians dressed in their brightest colors was very picturesque, but I should have enjoyed it better had the weather been a little warmer. About 9 o’clock a.m. we reached the camp, very cold and hungry. Gov. Stevens gave us a cordial welcome, and, after expressing his gratification at at [sic] the sight of so many canoes filled with well dressed Indians, he directed us to the camp fort, where he had ordered a breakfast to be ready for us, and we soon had a hearty meal of beef steak, potatoes, hot biscuit and coffee, and were then shown to our tents. Dr. Cooper and I had one tent assigned us, the next to ours was occupied by Col. Mike T. Simmons, United States Indian agent, Judge Sidney Ford, sub-agent, and Sub-Agent Tappan. After we had arranged our quarters we took a look around to see the lay of the land.

The camp ground was situated on a bluff bank of the river; on its south side, about ten miles from Grays harbor, on the claim of Mr. James Pilkington. A space of two or three acres had been cleared from logs and brushwood, which had been piled up so as to form an oblong square. One great tree which formed the southern side of the camp, served also as an immense back log, against which our great camp fire and sundry small ones were kindled, both to cook by and to warm us. In the center of the square, and next to the river, was the governor’s tent, and between it and the south side of the ground were the commissary’s and other tents, all ranged in proper order. Rude tables, laid in open air, and a huge frame work of poles, from which hung carcasses of beef, mutton, deer, elk and salmon, with a cloud of wild geese, ducks and other small game gave evidence that the austerities of Lent were not to form any part of our services.

Around the side of the square were ranged the tents and wigwams of the Indians, each tribe having a space allocated to it. The Coast Indians were placed at the lower part of the camp; first the Chinooks, then the Chehalis, Quenaiults[,] Queets, Satsop, Upper Chehalis and Cowlitz. These different tribes had sent representatives to the council, about 350 of them, and the best of feeling prevailed among all. The white persons present consisted of only fourteen. Gov. Isaac Stevens, George Gibbs, who officiated as secretary of the commission; Judge Sidney S. Ford and his two sons, Sidney and Tom, who were assistant interpreters; Lieut.-Col. B.F. Shaw, the chief interpreter; Col. Mike T. Simmons, United States Indian agent; Mr. Tappan, sub-agent; Mr. Pilkington, the owner of the claim; Col. H.D. Coch, Dr. Cooper and myself, and last, but by no means the least, Orrington Cushman, our commissary, orderly sergeant, provost marshal, chief storyteller, factotum and life of the party. Nor must I omit Green McCafferty, the cook, who had become famous for his exploits in an expedition to the Queen Charlotte islands to rescue some sailors from the Haida Indians. He was a good cook and kept us well supplied with hot biscuits and roast potatoes, hot coffee and savory dishes from the meats and game.

The chief interpreter, Col. Shaw, had not arrived and the governor concluded to defer the treaty until he came, as he was not only the principal means of communication with the Indians, but was to bring some chiefs with him. Col. Coch and a party of them, therefore, went down the river to Armstrong’s point to meet him, while we passed the day telling stories and preparing for the morrow.

Our table was spread in the open air and at breakfast and supper was sure to be covered with frost, but the hot dishes soon cleared that off, and we found the clear, fresh breeze very conducive to a good appetite.

After supper we all gathered around the big fire to smoke our pipes, toast our feet and tell stories. While thus engaged we heard a gun fired down the river, and shortly the party arrived having Col. Shaw with them. He had brought a few Cowlitz Indians and a couple of Chinooks, but as he was very tired he had not much to say that evening, so we shortly went to bed. Next morning the council was commenced, the Indians were all drawn up in a large circle in front of the governor’s tent, and around a table on which were placed the articles of the treaty and other papers. The governor, Secretary Gibbs and Col. Shaw sat at the table and the rest of the whites were honored with camp stools to sit around as a sort of guard, or as a small cloud of witnesses. Although we had no regimentals on, we were dressed pretty uniform. His excellency, the governor, was dressed in a red flannel shirt, dark frock coat and pants tucked in his boots miner fashion, a black felt hat, with a clay pipe stuck through the band, and a paper of fine cut tobacco in his pocket.

The pipe being from time immemorial an emblem of peace among the savages, we all had ours, not, however, in our hat bands, but as we were not expected to speak, we preferred them in our mouths. We were also dressed like the governor; not in ball room or dress parade uniforms, but in good, warm serviceable clothes.

After Col. Mike Simmons has marshaled the savages into order an Indian interpreter was selected from each tribe to interpret the [Chinook] jargon of Col. Shaw into such language as their tribes could understand. The governor then made a speech which was translated by Col. Shaw into jargon, and spoken to the Indians in the same manner as the good old elders of ancient times were accustomed to deacon out the hymns to the congregation. First the governor spoke a few words, then the colonel interpreted, and the Indian interpreters; this threefold repetition made it rather a lengthy operation.

After this speech the Indians were dismissed until the following day, when the treaty was to be read. We were then requested by the governor to explain to those Indians we were acquainted with what he had said, and they all seemed satisfied. Gov. Stevens purchased of Mr. Pilkington a huge pile of potatoes — about 100 bushels — and Commissary Cushman and Col. Simmons were detailed to stand guard and see that every Indian received his or her share. This they did with utmost good feeling, keeping the savages in a roar of laughter by their humorous ways.

At night we again gathered around the fire and the governor requested that we should enliven the time by telling anecdotes, and, as every man present had a good experience of frontier life, every one responded, and there were some wild and weird tales told round that camp fire every night; of toil, privation, fun and frolic, but the palm was conceded to Cushman, called by his friends “Devil Cush,” who certainly could vie with Baron Munch[h]ausen, or Sindbad, the sailor, in his wonderful romances. His imitative powers were great, and he would take off some speaker at political gathering or a camp meeting in so ludicrous a style that even the governor could not preserve his gravity, but would be obliged to join the rest in a general laughing chorus. Whenever Cushman began his harangues he was sure to draw a crowd of Indians who seemed to enjoy the fun as much as we did, although they could not understand a word he said. He usually wound up by stirring up the fire; and this blazing up brightly and throwing off a shower of sparks, would light the old forest, making the night look blacker in the distance and showing out in full relief the dusky, grinning faces of the Indians, with their blankets drawn around them, standing up just outside the circle where we were sitting. Cushman was a capital man for a camp expedition, always ready, always prompt and good natured. He said he came from Maine; whether he did or not, he was certainly the main man among us.

A report of the anecdotes told in that camp would make as good a book as Joe Miller’s.

The second morning after our arrival the terms of the treaty were made known. This was read line by line by Secretary Gibbs and interpreted by Col. Shaw to the Indians who all seemed satisfied, except a few who wanted the reservation on their own land. I think the governor would have eventually succeeded in inducing them all to sign had it not been for the son of Carcowan, the old Chehalis chief. This young savage, whose name was Tleyuk, was the recognized chief of his tribe and had obtained great influence among all the Coast Indians. He was very willing at first to sign the treaty, provided the governor should select his land for the reservation and make him grand tyee, or chief over the whole five tribes; but when he found he could not effect his purpose he changed his behavior and we soon found his bad influence among the other Indians, and the meeting broke up that day with marked symptoms of dissatisfaction. This ill feeling was increased by old Carcowan, who smuggled some whiskey into the camp and made his appearance before the governor, quite intoxicated. He was handed over to Provost Marshal Cushman, with orders to keep him quiet until he was sober. The governor was much incensed at the breach of his orders, for he had expressly forbidden either whites or Indians bringing one drop of liquor into the camp.

The following day Tleyuk stated that he had no faith in anything the governor said, and that evening the governor called the chief to his tent, but to no purpose, for Tleyuk made some insolent remark and peremptorily refused to sign the treaty, and, with his people, refused to have anything to do with it. That night, in his camp, they behaved in a very disorderly manner, firing off guns, shouting and making a great uproar. We did not care a pin for their braggadoc[c]io, but the governor did, and the next morning, when the camp was called, he gave Tleyuk a severe reprimand, and, taking from him the [skookum] paper which had been given to him to show that the government recognized him as chief, he tore it to pieces before the assemblage. Tleyuk felt this disgrace very keenly, but said nothing. The paper was to him of great importance, for they all look on a printed or written document as possessing some wonderful charms. The governor then informed them that as all would not sign the treaty it was of no effect and the camp was then broken up. We had been in that camp one week and ample time was given them to thoroughly understand the treaty, and all was friendly until the last day, when Tleyuk’s bad conduct spoiled the whole. Subsequently, however, Col. Shaw and Indian Agent Simmons made a treaty which was approved by Gov. Stevens, by which the present Quenaiult reservation was set off and has since been occupied till the present time, so that, in fact, the work of Gov. Stevens at the treaty camp on the Chehalis, was not wholly abandoned, but has been the means of doing much good among the Coast tribes, and should be counted among the treaties made by Gov. Isaac I. Stevens.

— from the Seattle (WA) Post-Intelligencer of July 18, 1897, page 16, columns 6-7