Claims! Irrealis versus realis subordinate clauses!

With a grateful tip of the hat to Professor Leslie Saxon of the University of Victoria’s Department of Linguistics.

I had long assumed that the ways we “mark” subordinate clauses, when we speak them, reflects our assumptions about their True/False value.

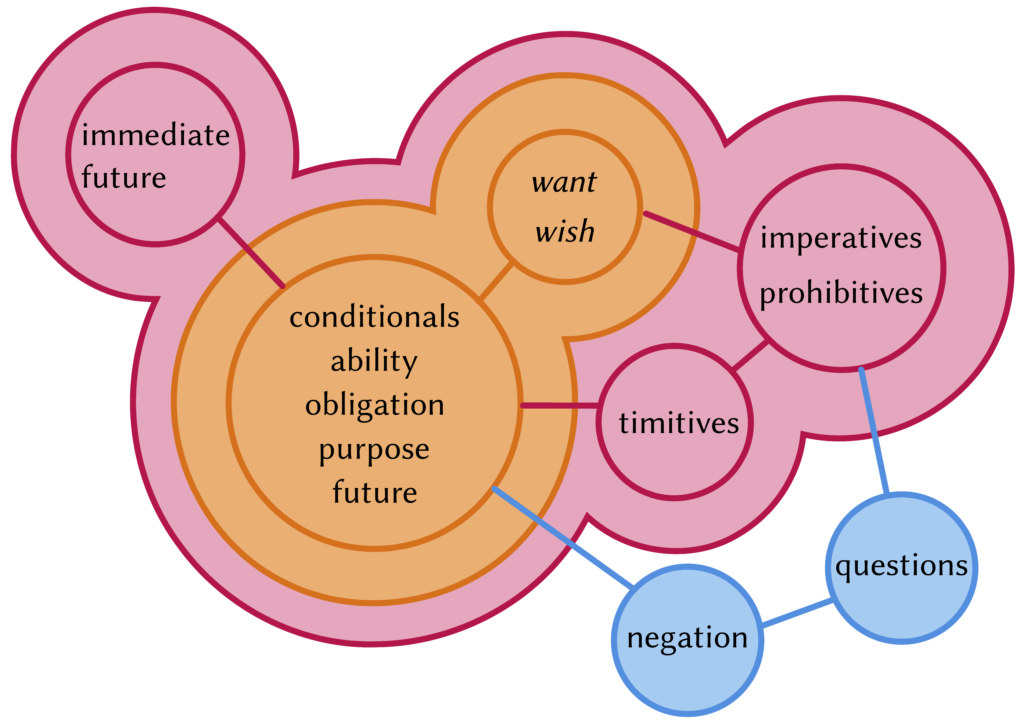

Image credit: Kilu von Prince

Uh-oh, there’s 2 ASSUMES in one sentence. Slippery ground!

Indeed, I’ve wound up learning something that has changed my assumptions about all that. I’ve done so by paying attention to Chinuk Wawa for over a quarter of a century.

So now, I claim instead that it’s all about claiming.

Let me take a sec to sorta explain, without getting very technical.

Sticking with CW for simplicity’s sake, I can tell you that I at first analyzed the Jargon as having basically two subordinate-clause markers: silence (Ø) when a subordinate clause is factual, and pus to introduce a subordinate clause that’s non-factual.

Simple examples of a kind that I see all the time in this language (written in BC Learners Alphabet, underlining the subordinate clauses) —

- Tloosh-tumtum naika (Ø) maika chako.

‘I’m glad that you came here.’ - Tloosh-tumtum naika pus maika chako.

‘I’d be glad if you came here.’

The only thing that changes our interpretation of Tloosh-tumtum naika and maika chako is the choice of subordinate-clause marker. (In orange.) Using (Ø) makes the following clause a reality. Using pus makes the following clause hypothetical.

And this brings us to a more accurate way of talking about the differences between the (Ø) clauses & the pus clauses — it’s really more about how the speaker sees a situation.

- With (Ø), the speaker sees the state of affairs in the subordinate clause as having definitely occurred (“realis” in linguistics).

- With pus, the speaker sees the subordinate clause’s state of affairs as potentially occurring. (“Irrealis” in linguistics.)

A neat variant on example 2 above: You can force pus into a less “irrealis” sense (so, meaning ‘when’ something definitely occurred, instead of ‘if’ it were to do so), if you just reverse the order of its clauses, like this:

3. Pus maika chako, tloosh-tumtum naika.

‘When you came here, I was happy.’

The thing is, I still see things this way. But a new wrinkle has come to my attention within this neat pattern.

Look at these examples from “Kamloops Wawa” #92 — written in that newspaper’s spellings — that may cause you some thought:

REALIS Ø,

but not assuming that the subordinate clause had already happened:

- Naika na tliminhwit-wawa Ø hlwima tilikom

‘Did I tell lies that other people’

mamuk ikta masashi?

‘had done something bad?’ - Naika na sahali-tomtom …

‘Was I stuck-up …’

ilo mamuk-tomtom Ø ST patlach kanawi tlus kopa naika?

‘not considering that God gave everything that’s good to me?’

IRREALIS PUS (that…might),

but assuming that the subordinate clause was likely to have happened:

- Naika na shim pus piltin tilikom ihi kopa

‘Was I ashamed that sinful people might laugh at’

tlus wawa?

‘good words?’

How does all of this fit into your understanding of Chinook Jargon?