PS: some Chinuk Wawa dialects have “exterior-heads”

Is your head outside of your body? Talkin’ about exocentric compounds!

Image credit: My World

These expressions, of which English “knothead” (which isn’t a knot or a head, it’s a foolish person) and French “casse-tête” (which isn’t a break or a head, it’s a crossword puzzle) are examples, haven’t been found in the Northern Dialect.

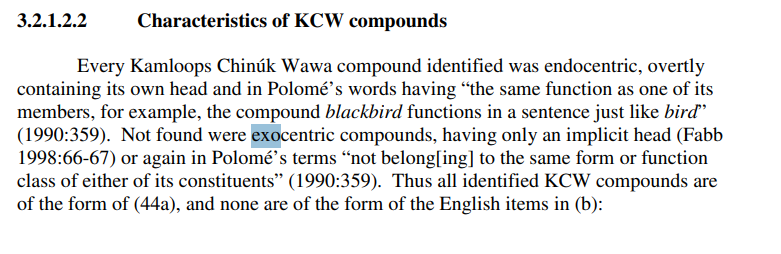

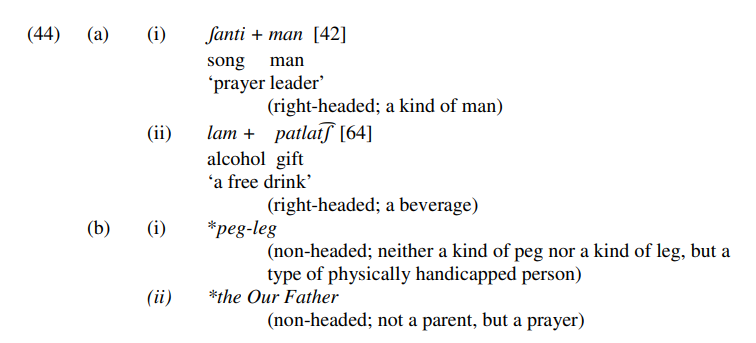

The only compounds in Northern Chinook Jargon seem to be “endocentric”, where for example a liplett-hous is indeed a kind of house (a ‘priest(‘s) house/quarters’).

Here’s what my dissertation said a few years ago, and I stand by it, for the Northern Dialect that it’s describing. The funny tall ∫ represents the “sh” sound…

But this is one of the real differences with the Southern Dialect — and, as I understand things, with the oldest dialect, Central, of Fort Vancouver.

There, it’s not uncommon to find both the above self-explanatory endocentric compounds, but also exocentric ones like these:

- hə́m-latét (this isn’t a “smell” or a “head”, but a bird, the buzzard)

- músmus-latét (not a “cow” or a “head”, but an epithet for K’alapuyan tribal people!)

- sə́x̣-úpuch (which is neither a “rattle” nor a “tail”, but a rattlesnake)

- lots of X-tə́mtəm expressions of internal psychiatric states, like say táyi-tə́mtəm ‘dignity’ (not a kind of ‘chief’ nor necessarily a ‘heart’)

Some points:

There isn’t yet much of a linguistic literature on Chinuk Wawa compounds. That’s one reason why I wrote my dissertation. Now it’s time to expand on my observations, and on those of Henry Zenk (1993), who may have been the first to comment on the endocentric ones.

(And on Active vs. Stative verbs in this language!)

So I have some typological points to make:

1st: It seems to me that exocentric compounds, in any language that has them, are less frequent than endocentric ones.

2nd: I also think exocentric compounding is less “productive” than endocentric, in the sense that you can’t freely produce these with predictable meanings. (Cf. this from Laurie Bauer.)

3rd: Additionally, I wonder if a couple of semantic fields are particularly receptive to participating in exocentric compounding:

(A) as components, Body-Part Nouns (typically of humans and critters big enough to seem like they have personalities; and typically inalienably possessed organs), and

(B) as resulting forms, Personal Names including nicknames.

In both regards, my thinking is that the easier it is for the hearer to figure out who or what’s being referred to (e.g. from a really noticeable feature of their body), the more successful an endocentric compound is, and the more likely to be retained in common use, thus reinforcing clarity of reference. For a similar example, albeit not a compound noun in my analysis, take the historic Grand Ronde tribal member who was known as háyásh-tutúsh ‘big breasts’.

I’ll also say that I’ve tried to keep the comparisons here mostly among Noun+-Noun compounds. That’s by far the most normal (endocentric and exocentric) compound in all dialects.

Even though the seeming Verb+Noun compound q’wə́ɬ-q’wəɬ-stík ‘a woodpecker’ is of old historical vintage, I’ve long maintained that it’s a real oddball of a Jargon word, evidently modeled on Métis/Canadian French pic-bois.

A last thought: personally I’ve long wished that every phrase involving a given “word” of Chinuk Wawa would be listed under that word’s entry in the Grand Ronde Tribes dictionary. As is, you can find any phrase that begins with that word. You’d be much empowered if you could also see, in the same entry, all the phrases having that word in their middle or end.