Central and Southern Chinook Jargon have a definite article “uk=”…but why isn’t it “lə=”?

This I find to be a nifty question.

Image credit: Wikipedia

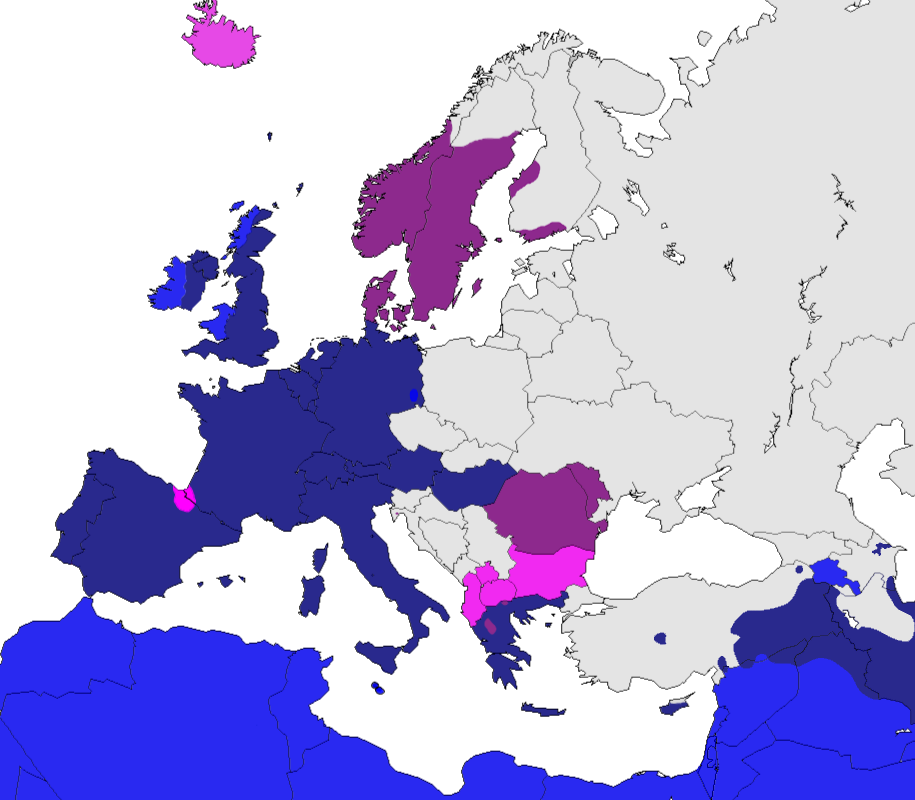

Articles in languages in and around Europe

Key:

DARK BLUE: indefinite and definite articles

BLUE: only definite articles

DARK RED: indefinite and suffixed definite articles

PINK: only suffixed definite articles

GREY: no articles

In Louis-Napoléon St Onge’s manuscript dictionary of the Central (i.e. the oldest) dialect of Chinuk Wawa, he remarks:

The was rendered by the expression ok’ which is an abbrev[iation]. of okuk. Bishops [François-Norbert] Blanchet & [Modeste] Demers always used it.

It’s abundantly clear, from that remark, that we are indeed talking about the Central Dialect. This is because Blanchet & Demers were working in the Fort Vancouver area a generation before the Southern Dialect (of Grand Ronde Reservation) could have existed.

At Grand Ronde, as you can learn from their utterly splendid 2012 dictionary of Chinuk Wawa, uk as they spell it is ‘that, this, the’ — that is, as a specifying word right before a noun phrase (NP).

(Note: I’ll represent uk= without an accent mark, as it’s unstressed, and with an equals sign, showing “proclitic” status, a loose attachment to a following word.

(My linguistic analysis terms uk= a Determiner because it has to be accompanied by that NP; the NP is what does have stress on it.

(Specifically, the type of Determiner that uk= is, is a Definite Article.

(The GR dictionary calls uk= a pronoun, which however is a function that a word can have only when it by itself is the entire, stressable NP, without a noun buddy.

(But the etymological source of uk= (úkuk ‘that (one), this (one)’, which remains in use in the language) can certainly be not just a Determiner, but often a pronoun.)

Another important fact about ok(‘) / uk= is that this Definite Article is optional.

The perfectly fine Wikipedia article “Article” 😒tells the truth: many or most of the world’s 6000 or so languages have no articles — and in those that do, (the) use of articles is optional.

In this respect, Central and Southern Chinook Jargon are boring, average languages. They don’t use uk= nearly as often as English uses “the”, or as Métis/Canadian French uses “l’/le(s)/la”. Where those 2 Indo-European parent languages of the Jargon say, for instance:

The girl gave the boy the bread.

La fille a donné le pain au garçon.

…with a Definite Article on all 3 “arguments” of the verb for ‘giving’, it would be bizarre to hear in Chinuk Wawa the equivalent syntax:

* uk= tənəs-ɬúchmən yaka pálach uk= saplél kʰapa uk= tanas-mán.

You know a linguist has a STRONG opinion when they put an asterisk before an example, like I just did! Using so many uk=‘s is wrong to my ear. Bad Jargon.

To say the least, Chinuk Wawa likes to say the least.

This language, like every other human speech variety, values your precious breath. Be economical when speaking Chinook! “Just the bullets, dear one,” as the respected elder Vi Hilbert used to advise. (To linguists!)

You don’t lose much information by dropping some (or often, all) of the possible uk=‘s.

For one thing, ‘the girl’ is already definite because of the inflection of the verb with the optional pronoun yaka, so we’re already good to go ahead & say:

√ tənəs-ɬúchmən yaka pálach uk= saplél kʰapa uk= tanas-mán.

(Having the exact same meaning.)

That check-mark is the opposite of an asterisk to this linguist — with it, I’m saying “Yay! Good Jargon!”

On a similar point, ‘the boy’ is pretty darn definite (and forgive me for saying this next thing, because hard linguistic data is full of triggers) — by virtue of being

- (A) animate

- (B) human

- and (C) masculine.

Typological linguistic research has proved that all human languages share the tendency to give different (I didn’t say ‘special’ 😊) grammatical treatment to such entities, in what we call a “hierarchy” of “animacy” or “affectedness”. Meaning that it’s also totally OK to say:

√ tənəs-ɬúchmən yaka pálach uk= saplél kʰapa tanas-mán.

(Again having precisely the identical meaning.)

And here’s where we bring in the actual fact that, in living conversation, about ¾ of the time, you as a participant are well aware whether some ‘bread’ being talked about is co-referential with a “known” instance of bread. If it’s “old information” (yes, all of these are linguistics terms! You can be a linguist too!), it’s Definite. But if it’s Definite, do you really need to restate that fact, by adding another word, our uk=? Nope.

The proof of this is in the Northern Dialect, which has no equivalent for uk=. And we understand each other mighty well in the North when we say:

√ tənəs-ɬúchmən yaka pálach saplél kʰapa tanas-mán.

(Yep, still the same meaning.)

A shortcoming of the way we linguists present our arguments and proofs is that we do the scientist thing, simplifying things down to a usable, idealized picture. Some stuff I’ve left out here includes

- (1) “intonation” which can help us make a difference between pálach saplél ‘give bread’ and pàlach-saplél ‘be “bread-giving”, TL:DR), and so on;

- (2) the fact that you can just use the full úkuk at any time, in all dialects;

- (3) the flexibility of any language’s syntax, such that we know (especially from the massive data we’ve got on the Northern Dialect) that the Jargon defaults to definiteness. If ‘bread’ were “new information”, we could have just placed it earlier in the sentence, like this:

√ tənəs-ɬúchmən, saplél yaka pálach kʰapa tanas-mán.

‘The girl, it’s (some) bread that she gave to the boy.’

√ saplél, tənəs-ɬúchmən yaka pálach kʰapa tanas-mán.

‘It’s (some) bread that the girl gave to the boy.’

I didn’t anticipate getting into a meditation this deep when I began writing today!

I’ll tie things up with a separate comment.

Always think about the negative evidence!

Why is the Definite Article, uk= in Chinuk Wawa’s Central & Southern dialects, from a Lower Chinookan word? Chinookan languages don’t even have Articles. (Despite a stray mis-wording or two by Franz Boas, who more cogently points out that the “Neuter” noun-class prefix also has Indefinite functions.)

Why didn’t this highly Indigenous language take in one or more of the already existing, very frequent Articles (t=, ti=, et al.) in its 2nd co-parent language Lower Chehalis Salish? Those even have the, let’s call it, “advantage”, of sounding similar to English the! Well, I can only tell you that vanishingly few Salish articles are evident in the known Chinuk Wawa data. These were evidently not often heard in CW speech. And the Salish articles are optional, particularly in “citation form” when you’re saying a word in isolation pidgin-style, not in a sentence of Salish.

A 3rd co-parent language, English, has the= all over the place. But the culture of speaking English has us leave out “the=” when we’re using nouns in their “citation form”. Maybe this has some relevance. We think the English-sourced words at the time of early-creolizing Chinook Jargon date back a generation earlier yet, to the first, pidgin days of CJ, a time when everything was isolated words of Nuučaan̓uɬ (“Nootka”) and English and Chinookan and Lower Chehalis strung together.

And why didn’t the Jargon just extrapolate the Article(s) of the 4th co-parent language of the Jargon, French? It’s super clear, from the forms of almost every Noun, and some of the Adjectives, of French origin in Chinuk Wawa, that folks were constantly hearing le=, la=, and les=.

Well! Here we know that the speakers of early-creolizing CW (that is, Central dialect, of Fort Astoria and Fort Vancouver), far more than half of whom (being the Indigenous wives and the Métis kids of the already part-Metis fur trade staff) did not quite know what to make of all those “L-type words”…

It would seem as if these mostly non-Indo-European-speaking folks quite optimally folk-analyzed this “L” shape as being a Noun Class Marker. Their Indigenous languages abound with such morphology: i-/u-/ɬ-/t- et al. in Chinookan, s- in Salish, a(N)- in K’alapuyan, and so on. (Also: linguist Peter Bakker has pointed out that pidgin languages sometimes cling onto noun-class marking.) That analysis is 100% perfect. I mean, it’s fully compatible, no hiccups, with everything else about Chinuk Wawa’s grammar.

They could’ve for example instead taken the “L’s” as being Possessor marking on nouns (which also would match Indigenous languages’ grammar), but this then would conflict with how we observe from the earliest times that it’s the Chinookan-derived personal pronouns that are used to indicate possession in Jargon.

Not to extend this thought experiment into silliness, but even if these folks had instead tried to understand the “L’s” as, say, Inalienable (or Alienable) Possession marking (analogous to their Indigenous languages), this too would have been a bad guess. Less than half of the “L” nouns in Jargon, maybe more like ¼, are permanently-possessed things like body parts: lima ‘hand’, laparp ‘beard’, lipʰyi ‘foot’.

All in all, I’m not sure we can claim this outcome was predictable, but:

We can see good reasons why early-creolizing Chinuk Wawa enlisted existing resources from no language but Lower Chinookan, in whose territory Fort Astoria and Fort Vancouver stood, to create a Definite Article. That reason? Everybody already knew & heavily used the Chinookan-sourced CW Demonstrative and Pronoun, ukuk.

That said, we’ve seen there were speakers of at least 3 other major input languages accustomed to using Definite Articles all the time (outside of Chinuk Wawa). So it may well have been those, largely non-Indigenous, folks who supplied the behavioral pressure to overtly specify CW nouns.

What a mix, eh!

Bonus bonus fact:

I have previously written on how “definiteness” (in its essential meaning of “previously established information”) can be seen as showing up in the Perfective versus Imperfective aspect of verbs in Chinuk Wawa.