Lempfrit’s legendary, long-lost legacy (Part 25b, Credo)

We’ve seen H-T Lempfrit’s manuscript dictionary; and now for some rare old Chinook Jargon texts on its following pages!

The 25th pair of pages (mis-numbered as “24” on the original page) from this precious document again brings us plenty of stuff worth knowing about Chinook Jargon — this time moving from lists of words into texts.

Image credit: CreationSwap

(Here’s a link to the other posts in this mini-series.)

“[SIC]” shows that someone mis-wrote a word. It wasn’t necessarily Lempfrit, since he was copying from someone else’s manuscript, Modeste Demers’ now-lost original to be exact.

For today’s installment, Alphonse Pinart’s “Anonymous 1849” copy (read it for free online) lacks any pages that correspond to what we’re seeing from Lempfrit.

Where you see [le]tters in square brackets, they’re not visible on the page copy that I’m working from, but we infer that they really are there!

By the way, the notation ___ means that the preceding entry is repeated in that position, along with some additional word(s).

See if you recognize words in these unusual spellings! I think we have a couple more small discoveries today, again showing the value of examining every Chinuk Wawa document — even those that appear to be straight copies of each other!

Beginning with today’s textual materials, we have the rewarding experience of seeing how a French-speaker (in the pre-Anthropology era, no less) conceptualized the word-to-word flow of spoken Jargon. Lempfrit’s “glosses” of each Chinook Jargon word might be pretty different from how you think of each word’s meaning!

If you need some quick proof that Chinook Jargon is an Indigenous language, take a look at how different Lempfrit’s French, and the conventional English lines, are from what the Jargon here is literally — and fluently — saying.

When I say that this Chinuk Wawa is fluent, I’m saying that it’s totally characteristic stuff from what I’ve now come to call the Central Dialect. That’s the oldest variety of the language, the early-creolized Jargon associated with Fort Astoria and Fort Vancouver. The document we’re looking at here was created before the Northern or Southern dialects (associated with British Columbia and with Oregon’s Grand Ronde Reservation, respectively) even existed.

Here I’ll suggest punctuation marks such as (.) or (:), to help my readers. I’ll also help you understand Lempfrit’s word-for-word translations from Chinook Jargon into a pidgin-like version of his native French, which give us an idea of how he thought about CJ — they’re very interesting.

There’s actually a ton to say about them, but I’m going to leave that, for now, to a student looking for a solid term paper or conference piece to write.

The following is the first part of the “Credo“, an English-language version of which is:

I believe in God the Father almighty, creator of heaven and earth. I believe in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord. He was conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary. Under Pontius Pilate He was crucified, died, and was buried.

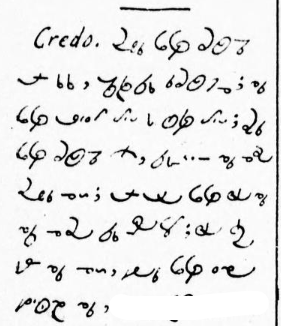

Credo

1º Naïka komtaks nawiteka

Moi penser vrai

‘I know indeed’sahalé Tayé Papa ayas skoukoum

Dieu père très fort

‘God the father is very powerful;’yaka mamouk sahali pi éléhé

lui avoir fait le ciel et la terre

‘he made the sky and the land;’2º Kopet hihkt yaka tanas

rien qu’un son fils

‘He has just one child,’Jésuclit nsaika Tayé

JC notre chief.

‘Jesus our chief.’3º Okouk tlosh tomtom patlash*

Celui-là ce* bon esprit donner

‘That good spirit gave’yaka kopa Mali kopa Mali

lui à Marie de Marie

‘him to Mary; it was to Mary’yaka tshako tanas

lui donner enfant

‘he was born.’4º Pous kopa okouk tayé Ponce Pilate

Pendant ce chef Ponce Pilate

‘When it was with that chief, Pontius Pilate,’tlaska mamouk tlahawiam yaka

eux faire digne de pitié lui

‘he was made to suffer.’

This is fairly good Chinook Jargon, not great.

It’s very similar to (but less fluent & clear than) what we find in the Fort Vancouver-era translations by Fathers Blanchet and Demers, as published in 1871:

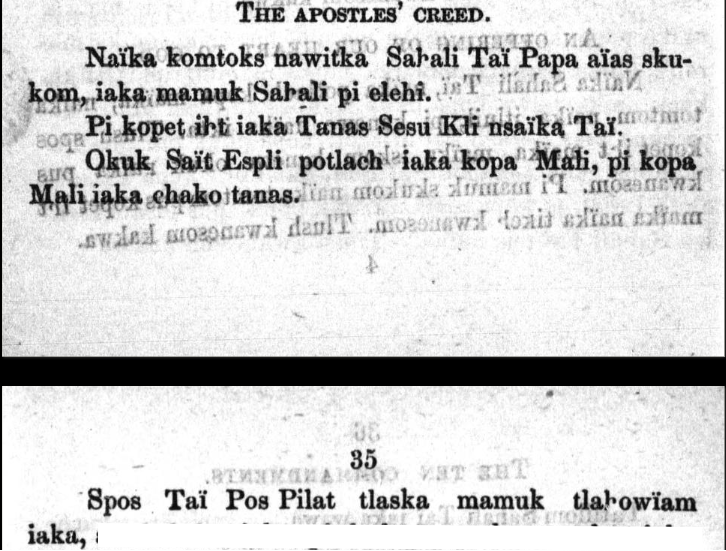

THE APOSTLES’ CREED.

Naïka komtoks nawitka Saիali Taï Papa aïas skukom, iaka mamuk Saիali pi elehi.

Pi kopet iիt iaka Tanas Sesu Kli nsaïka Taï.

Okuk Saït Espli potlach iaka kopa Mali, pi kopa Mali iaka chako tanas.

Spos Taï Pos Pilat tlaska mamuk tlaիowiam iaka, …

And that’s worth pointing out, because we’ve seen a steady stream of parallels between Lempfrit’s manuscript and the work of Blanchet & Demers.

For fun, compare this with a half-century later translation of the Credo:

Nsaika mamuk nawitka ST papa, skukum kopa kanawi ikta; iaka mamuk sahali ilihi pi ukuk ilihi; naika mamuk nawitka ShK, kopit iht iaka tanas nsaika taii; ST SS mamuk pus iaka iaka tanas kopa Tlus Mali; pus Pons Pilat iaka taii, klaska mamuk aias klahawiam iaka,…

‘We [SIC] believe God the father is powerful enough for (doing) anything; he made heaven and this earth; I [SIC] believe Jesus is the only child of our chief; God the Holy Spirit made it so he was the child of Blessed Mary; when Pontius Pilate was chief, he was made to suffer a lot,…’

Stay tuned for the next installment!