WA: Upper Skagit Valley place names, and salvaging language information

It’s not an unusual situation for proper names to be everything we know about some previously-existing language.

This happens in Europe, for example, where toponyms give us valuable clues about what was spoken in various regions prior to the arrival of present-day languages.

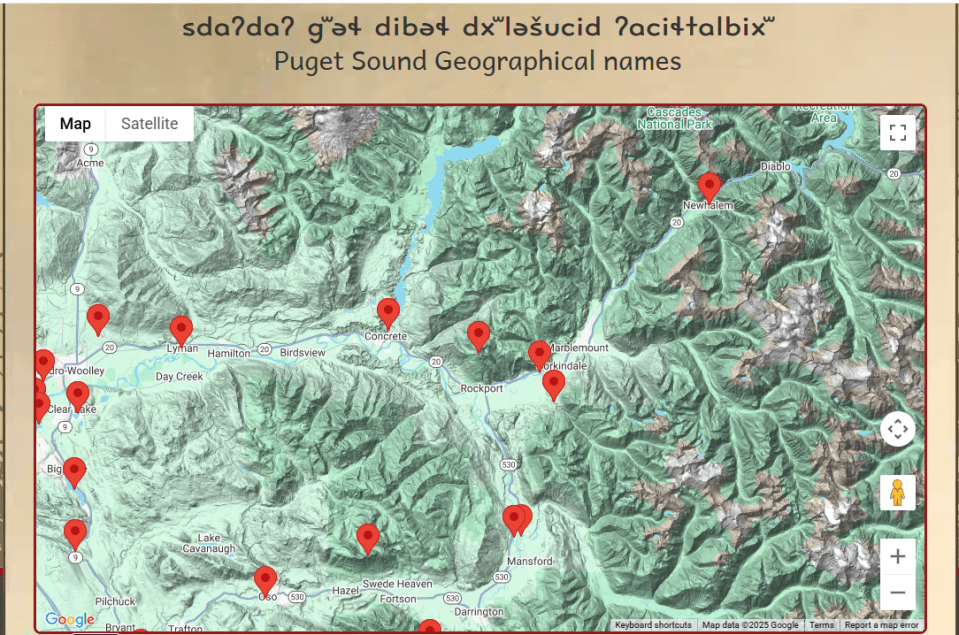

A great place to learn Lushootseed place names (image source: Tulalip Lushootseed)

And in many parts of the world, languages have gone silent, leaving only tantalizing single-word clues in the form of names.

In Washington State, we’re fortunate that the “Lushootseed” Salish language, that is, Dxʷləšucid / Txʷəlšucid, has been relatively well documented and understood.

Nevertheless, there are names on the map that can add to our knowledge of that language in some of the more far-flung areas where it’s traditionally been spoken.

I got thinking of this as I was driving through Upper Skagit & Sauk-Suiattle tribal territories in the upper Skagit Valley of Washington the other day. This is on Highway 20, the North Cascades Highway, one of the incredible scenic routes through this state.

As you enter the company town (yep, those still exist!) of < Newhalem >, you can see a sign with the more obviously Lushootseed form, < Daxʷálib >, on it. That actually sounds a little off to my ears, as if it were almost correct; I might have guessed dxʷʔíləb, but the existing dictionary of Lushootseed actually has (not cross-indexed in the English section! — a common dictionary problem), dxʷʔíyəb. Wikipedia, quoting Harry Majors’s “Exploring Washington”, suggests that this means ‘goat snare’ “in a local Indigenous language”. Again, I haven’t yet figured out any connection with known Lushootseed words for ‘traps’ or ‘(mountain) goats’, but that’s exactly the language it should come from.

In the same area, there’s < Diobsud > Creek, and the Noisy-Diobsud Wilderness. William Bright’s wonderful book, “Native American Placenames of the United States”, only offers that this is “perhaps a Lushootseed (Salishan)” word. A blogger known as Converse in the North Cascades helpfully adds:

Diobsud is an Indian word. Dad always said it means “foaming water”. I have heard other people say that Diobsud was the name of a chief who lived near there but the real Native word for the stream, which was not Diobsud, did mean “foaming water”. I have also heard that Diobsud means other things as well. No matter what the name was, I have always liked the meaning “foaming water” because this is a stream where you can pretty reliably find foam where the stream flows out of a constriction at the valley wall.

None of the people I have talked to who still understand Salish were familiar with the word Diobsud. The closest term anyone could come up with means “the other side of the river” or something like that. I wonder if the word was actually a term used only by the local band or sub-band of Skagits who lived in the area. There were quite a few separate bands along the river, each with its own name, and I would think, possibly with their own colloquialisms and local place names. These people collectively became known as Skagits at some point later, probably under a treaty of some kind. I’m not an expert on that history but it doesn’t sound like a very good time for Indian people when the white people moved in, though many were able to and did continue to live in the area.

The proper way to pronounce this name, as Native speakers did, as per my dad who heard Native speakers say it is: Die-oh-b-sud. People who grew up here usually say Die-oh-b-see or Die-oh-p-see. People who didn’t grow up here rarely get it right. I am sure it will morph into something unrecognizable to the original before too many years pass. Such is the way with some words but it is also kind of a shame to lose this little bit of history so unique to the place.

Using both the 1960’s and 1990’s editions of the Lushootseed dictionary, I haven’t yet pieced out how the name < Diobsud > is constructed.

But my own experience of working with Indigenous languages of our region confirms that it’s sometimes the memories of non-speakers that give us the needed clues to decipher more about a given language. And often, those clues are in the form of the names of places and of people. (Sometimes extremely entertaining nicknames!)

And yes, sometimes it’s Chinook Jargon words that we learn about from place names. I’m thinking, for example, of how this has been a useful source for us to learn northern coastal CJ phrases like church-house…