Poser 2003 on ᑐᑊᘁᗕᑋᗸ…there are many parallels with Chinuk Pipa

I’m in the business of checking everything that’s said in the scholarly world about Chinook Jargon, so today I’ll have a look at a paper by my friend Bill Poser.

I’m talking about his excellent study, “Dʌlk’wahke: The First Carrier Writing System” from 2003.

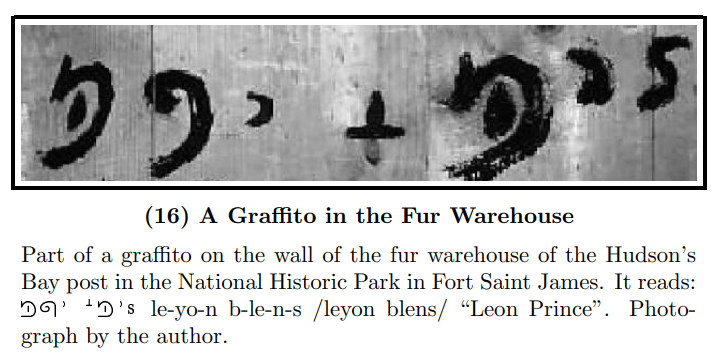

A further parallel between dʌlk’wahke and Chinuk Pipa:

there are special ways to show you’re writing a name;

here a plus sign, in CP a dotted underline

For us in the Chinook Jargon world, with our unique Chinuk Pipa ‘Chinook Writing’ alphabet from BC, it’s really neat to get a look at another Indigenous-language writing system from nearby.

Father Adrien-Gabriel Morice‘s invention and popularizing of the Dakelh a.k.a. Carrier Dene syllabary has many parallels with Chinuk Pipa‘s history. Known as dʌlk’wahke, ‘toad feet’, this set of symbols truly caught on among Indigenous people, being used for a large range of purposes including personal letters, a newspaper, and more.

For example, Bill tells us on pages 5-7, there are a number of grave headstones in the Dakelh language, all of which are in this syllabic writing, never in English-style letters. I would like to add that this shows another parallel with Chinuk Pipa, a writing system that everyone associated with a single language, Chinook Jargon. Thus, the grave markers in Chinuk Pipa in, primarily, Secwépemc Salish-speaking communities are nonetheless all in Northern-dialect Chinook Jargon.

Another common use of dʌlk’wahke (pages 7-8) was to write messages on blazed trees, which Bill brilliantly points out is a continuation of a traditional cultural practice from times before literacy was introduced. That same observation is surely valid with the Chinuk Pipa tree-blaze messages.

And here I’d link back to Bill’s comment, on page 2, that Father Morice himself always called the Dakelh syllabic script dʌčʌnk’ʌt ‘on trees’. This term is apparently not now known by Dakelh people, but contrary to Bill’s speculation that it “may never have gained currency among Carrier people”, I would think that this name itself suggests an Indigenous view of the syllabics.

Also on page 2, Bill notes how the dʌlk’wahke literacy was almost entirely due to Native people teaching one another. This is strongly paralleled, I have to point out, in Chinuk Pipa‘s history of initially being met with disinterest among Indigenous folks who Father JMR Le Jeune tried teaching it to, but then being eagerly learned once a tribal man began demonstrating it. It’s very meaningful that one elder told Bill of learning dʌlk’wahke “from my auntie, out on the trap line”!

In 1885, within weeks of Dakelh people starting to learn this writing, the earliest preserved text in it showed up on the wall of a jail in Richfield, BC, near Barkerville. The parallel that I can add is that Indigenous people also wrote graffiti with Chinuk Pipa writing.

Further, it’s notable that the long 1885 Dakelh jail text is not only in the Dakelh language; it contains the pidgin English-sounding line, dʌm bʌgar dis jel bagabil ‘Dumb bugger! This jail [is in] Barkerville’. (Page 11.) Here I find a strong parallel with how Indigenous speakers of Chinook Jargon often picked up English-language cuss words from their dealings with Anglophones.

On page 31, Bill follows Father Morice in evaluating Chinuk Pipa as (1) “adequate” for “the sounds of…the European version(s) of Chinook Jargon”, but (2) “a poor writing system for the [N]ative versions of Chinook Jargon and the Salishan languages”.

Point (1) is true as far as it goes, since Chinuk Pipa doesn’t scientifically distinguish all of the phonemes of the Jargon — and most Settlers probably were not so great at saying the ejective sounds, voiceless laterals, etc. Then again, standard English writing is terrible at exactly showing the sounds of English, y’know?

Point (2), in regard to Chinook Jargon, is very weak, because CJ has so few “words” (morphemes, lexemes, whatever terminology you enjoy) that it’s a nearly foolproof way of writing the language and being fully understood.

Point (2) is a stronger criticism of how 8 BC Salish(an) languages were written in Chinuk Pipa, but again, from my personal experience, a linguist can understand 99% of the words and a mother-tongue Indigenous speaker would’ve had little trouble doing the same. In fact, we have various Chinuk Pipa documents in at least 2 Salish languages, Nɬeʔkepmxcín and Secwepemctsín, written by Native people.

Let’s not ignore that on page 30 Bill acknowledges dʌlk’wahke itself “failed to provide for some distinctions” of phonemes. I note it’s a universally understood fact, among linguists who research writing, that essentially every language’s writing system just plain leaves out contrasts that a fluent speaker knows without visually specifying them. It’s never a big enough problem to get folks to fix their alphabet, syllabary, what have you. I’ve often encountered a pitch-accent or tone language whose speakers never show pitch or tone; the Cherokee syllabary is far from comprehensive for that language; there are countless languages with contrastive stress that’s essentially never marked in writing (Chinook Jargon!); etc. Not a big issue.

Morice also failed to note that syllabic writing such as the dʌlk’wahke is very poorly suited for Salish languages. In contrast with the Dene (Athabaskan) family of languages that includes Dakelh, Salish languages tend to frequently use much more complexly structured syllables. We linguists in fact argue endlessly about how to define syllables in Salish! This, in my understanding of the historical events from those personally involved, was the major reason why Duployan shorthand was adopted instead of syllabics for writing Salish and Chinook Jargon.