1843-44, OR and CA: “Captain Fremont’s Second Exploring Expedition — Continued”

Comments about a Chinook young man (Billy Chinook) accompanying the famous Captain John C. Frémont’s second exploring expedition into California reveal how hugely important Chinook Jargon was, at least half a century into its existence.

Image credit: Granger

There was a whole lot of nationwide newspaper coverage of Frémont’s 1843-1844 journeys, so it’s not hard to find accounts like the following:

The expedition commenced its homeward match

on the 25th of November. “At the request of Mr.

Perkins,” one of the missionaries at the Dalles —“A Chinook Indian, a lad of nineteen, who was extremely

anxious to ‘see the whites,’ and make some acquaintance with

our institutions, was received into the party, under my special

charge, with the understanding that I would again return him

to his friends. He had lived for some time in the household

of Mr. Perkins, and spoke a few words of the English lan-

guage.”

— from the Washington (DC) Daily National Intelligencer and Washington Express of August 21, 1845, page 2, columns 1-6

This “lad” was William “Billy” Chinook, and the characterization of “a few words of English” matches how a number of newcomers to the Pacific Northwest, ignorant of Chinook Jargon, perceived CJ.

It tells us a lot that William, born at essentially the time Fort Vancouver was founded, and raised in the one part of our region that had regular contact with non-Indigenous folks, didn’t speak good English.

Clearly he was using CJ much more, as did your average resident of the lower Columbia River in that time before Settlers became numerically and socially dominant.

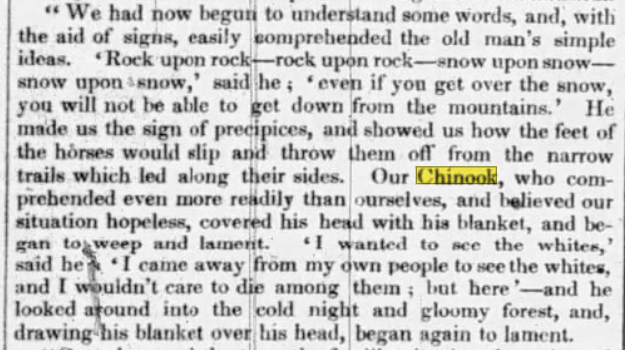

This young man is quoted reacting to some distressing news while the group is in California:

“We had now begun to understand some words, and, with

the aid of signs, easily comprehended the old [local Indigenous] man’s simple

ideas. ‘Rock upon rock — rock upon rock — snow upon snow —

snow upons snow,’ said he ; ‘even if you get over the snow,

you will not be able to get down from the mountains.’ He

made us the sign of precipices, and showed us how the feet of

the horses would slip and throw them off from the narrow

trails which led along their sides. Our Chinook, who com-

prehended even more readily than ourselves, and believed our

situation hopeless, covered his head with his blanket, and be-

gan to weep and lament. ‘I wanted to see the whites,’

said he ‘I came away from my own people to see the whites,

and I wouldn’t care to die among them ; but here’ — and he

looked around into the cold night and gloomy forest, and,

drawing his blanket over his head, began again to lament.

I take Frémont’s evocative translations here as a kind of unearned self-confidence, since he himself seems never to have spent enough time in CJ-speaking country to get much handle on it.

Also, Frémont specifies that most of his group’s communication with Native people in California was “only by signs”, meaning gestures.

Chinook Jargon in 1844 wasn’t yet widely spoken beyond the lower Columbia.

But Frémont was no slouch with languages. On the contrary!

Like many other trapper / mountain man types, he already spoke some “Shoshonee”, he tells us, and got good use out of that partway southwards into California, where various tribes speak languages related to it.

And he’s quick to note some words of what may have been the Washoe language around Lake Tahoe: tah-ee for ‘now’, and mélo for ‘friend’. (Is the latter from Spanish amigo?)

Take note also that Frémont’s long experience of meeting new tribes appears to have made him well skilled at gestural communication.

Put it all together, and reading this explorer’s telling of his unusually far-flung travels gives us an idea of the incredible linguistic diversity of western North America before English took over.