“Muck-a-muck” and Jargon history

Preceded by a piece from H.G. Dulog, who gave us the phenomenal Chinuk Pipa “Story of a Stump”, we have a Colorado newsman’s sober thoughts on an American slang word & Jargon history.

Image credit: Shore Heritage

I like this man’s careful thinking, his obvious experience with Chinuk Wawa, his information that in CW ‘food’ and ‘salmon’ are different things, and his conclusion that US slang “high muck-a-muck” did not come from the Jargon.

I only disagree with his claim that all early American visitors were considered “tyees”!

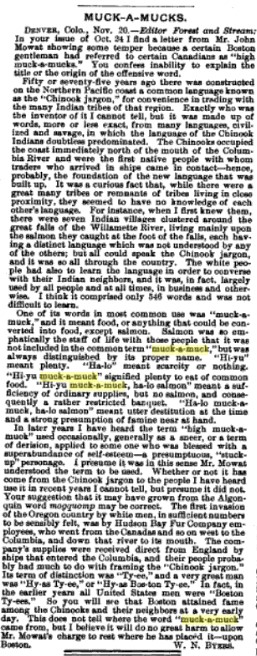

MUCK-A-MUCKS.

DENVER, Colo., Nov. 20 — Editor Forest and Stream: In your issue of Oct. 24 I find a letter from Mr. John Mowat showing some temper because a certain Boston gentleman had referred to certain Canadians as “high muck-a-mucks.” You confess inability to explain the title or the origin of the offensive word.

Fifty or seventy-five years ago there was constructed on the Northern Pacific coast a common language known as the “Chinook jargon,” for convenience in trading with the many Indian tribes of that region. Exactly who was inventor of it I cannot tell, but it was made up of words, more or less exact, from many languages, civilized and savage, in which the language of the Chinook Indians doubtless predominated. The Chinooks occupied the coast immediately north of the mouth of the Columbia River and were the first native people with whom traders who arrived in ships came in contact — hence, probably, the foundation of the new language that was built up. It was a curious fact that, while there were a great many tribes or remnants of tribes living in close proximity, they seemed to have no knowledge of each other’s language. For instance, when I first knew them, there were seven Indian villages clustered around the great falls of the Willamette River, living mainly upon salmon they caught at the foot of the falls, each having a distinct language which was not understood by any of the others; but all could speak the Chinook jargon, and it was so all through the country. The white people had also to learn the language in order to converse with their Indian neighbors, and it was, in fact, largely used by all people and at all times, in business and otherwise. I think it comprised only 546 words and was not difficult to learn.

One of its words in most common use was “muck-a-muck,” and it meant food, or anything that could be converted into food, except salmon. Salmon was so emphatically the staff of life with those people that it was not included in the common term “muck-a-muck,” but was always distinguished by its proper name. “Hi-yu” meant plenty. “Ha-lo” meant scarcity or nothing. “Hi-yu muck-a-muck” signified plenty to eat of common food. “Hi-yu muck-a-muck, ha-lo salmon” meant a sufficiency of ordinary supplies, but no salmon, and consequently a rather restricted banquet. “Ha-lo muck-a-muck, ha-lo salmon” meant utter destitution at the time and a strong presumption of famine near at hand.

In later years I have heard the term “high muck-a-muck” used occasionally, generally as a sneer, or a term of derision, applied to some one who was blessed with a superabundance of self-esteem — a presumptuous, “stuck-up” personage. I presume it was in this sense Mr. Mowat understood the term to be used. Whether or not it has come from the Chinook jargon to the people I have heard use it in recent years I cannot tell, but presume it did not. Your suggestion that it may have grown from the Algonquin word mogquomp [mugwump] may be correct. The first invasion of the Oregon country by white men, in sufficient numbers to be sensibly felt, was by Hudson Bay Fur Company employees, who went from the Canadas and so on west to the Columbia, and down that river to its mouth. The company’s supplies were received direct from England by ships that entered the Columbia, and their people probably had much to do with framing the “Chinook jargon.” Its term of distinction was “Ty-ee,” and a very great man was “Hy-as Ty-ee,” or “Hy-as Bos-ton Ty-ee.” In fact, in the earlier years all United States men were “Boston Ty-ees.” So you will see that Boston attained fame among the Chinooks and their neighbors at a very early day. This does not tell where the word “muck-a-muck” came from, but I believe it will do no great harm to allow Mr. Mowat’s charge to rest where he has placed it — upon Boston. W[illiam].N[ewton]. BYERS [1831-1903]

— from Forest and Stream, December 5, 1896, page 445

It would seem Byers was in Oregon Territory in the early 1850’s as a government surveyor. That was certainly a time when you had to know Chinook Jargon to get along well.

What about the Mowat article he refers to in the beginning?

LikeLiked by 1 person