Learning from the Lane learners (Part 4: ±alienable possession)

Are you ready to learn more from the excellent Chinuk Wawa students & teachers at Oregon’s Lane Community College?

“Chinuk-Wawa: Leyn-Skul, Buk 2”, a wonderful magazine created by Lane Community College’s learners of Chinook Jargon.

(Download / print it for free from this link.)

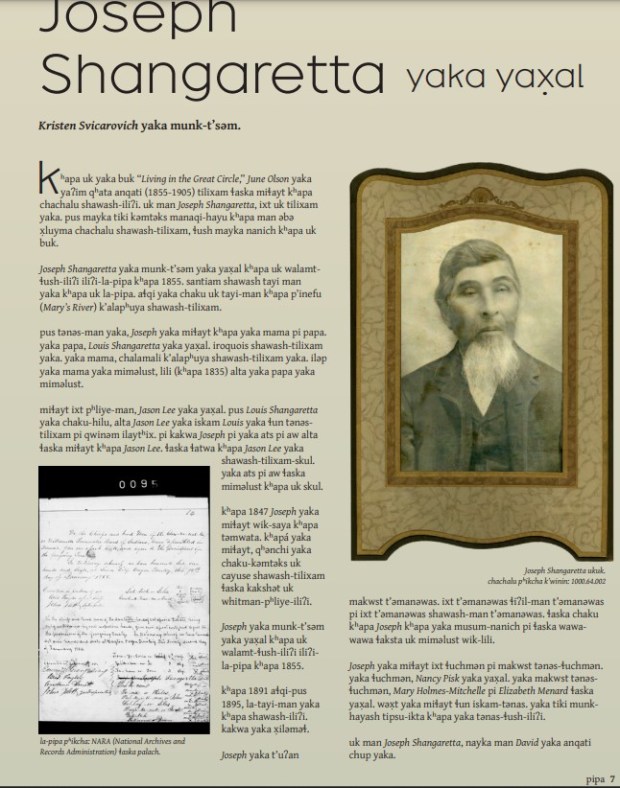

Page 7 carries an article, “Joseph Shangaretta yaka yax̣al” (written by / Kristen Svicarovich / yaka munk-t’səm).

The title translates as “Joseph Shangaretta was his name”, and this is a really interesting piece about an important Chalamali K’alapuya/Iroquois ancestor at the Grand Ronde reservation.

I noticed a couple of interesting things to focus on, and to contrast with Northern-dialect Chinuk Wawa, in its paragraphs.

- kʰapa = ‘about’ information, in the phrase …pus mayka tiki kəmtəks manaqi-hayu kʰapa man… ‘…if you want to know more about the man…’ I see this also on pages 8 & 12.

In the Northern dialect, we more often find …qʰata man…, which is literally ‘…how the man was / what the man was like’. - Before I make much of a single example, I’d like to hear more from Grand Ronde speakers about this next one. I perceive a sort of “alienable vs. inalienable” contrast between t’uʔan ‘have/own’ and miɬayt ‘have/be connected or related with’, in a couple of phrases:

- Joseph yaka t’uʔan makwst t’əmánəwas…

‘Joseph possessed 2 spirit powers…’

(but he didn’t always have them) - Joseph yaka miɬayt ixt ɬuchmən pi makwst tənəs-ɬuchmən.

‘Joseph had 1 wife and 2 daughters.’

(and they were permanently his relatives)

Grammatical distinctions between alienable & inalienable possession, foreign to the French & English inputs into the Jargon, are likely to be sourced in PNW Indigenous languages — although it can be hard to research this in languages lacking a written-up grammar description, because the dictionaries rarely explain ‘having’.

In the Northern dialect, we don’t have these 2 different verbs for ‘having’, just miɬayt. However, it’d be pretty normal in that dialect to say things in a way that reflects the “empathy hierarchy” a.k.a. “animacy hierarchy”, such as:

- (permanent having) —

(miɬayt) makwst nayka tənəs-ɬuchmən

‘I have 2 daughters’

(Literally, 2 are my daughters / there are 2 daughters of mine. Both I & my daughters are human beings, equally high on the hierarchy, so we’re both in grammatically non-object roles, subject & possessor.)

- vs. (non-permanent having) —

nayka miɬayt buk

‘I have a book’

(The book is much lower on the hierarchy than I am, so it can be the direct object of a verb of having, with me as the controlling subject.)

- (permanent having) —

- Joseph yaka t’uʔan makwst t’əmánəwas…

- A nice expression for a ‘foster child’ shows up in the same article, the Verb+Noun compound iskam-tənas (literally ‘a taking-child’), as in wəx̣t yaka miɬayt ɬun iskam-tənas, ‘he also had 3 foster children’.