Crowdsourcing challenge, continued: Swinomish letter in Chinuk Wawa

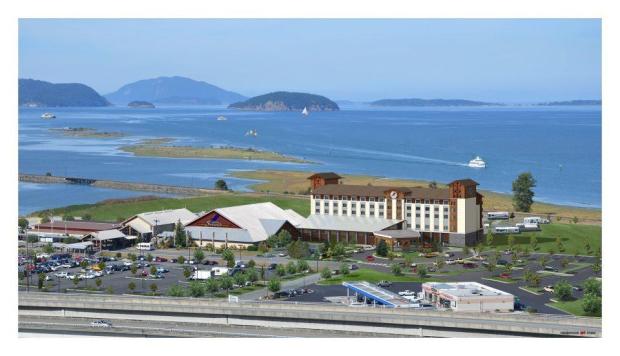

Swinomish (Image credit: Booking.com)

Three weeks ago, my readers helped find a pair of 1920’s letters in Chinuk Wawa; today I’m presenting the first to you. It’s very rich, fluent, heartfelt material.

I’m sorry I don’t have a photo of the letter writer, Wiliam (Willie) McCluskey. I do know that he had formerly been a millwright at Tulalip Reservation and a farmer in charge at Lummi Reservation. He’s quoted in the capacity of an authority on Lummi place names in a 1917 book. Various evidence in his letter and elsewhere suggests he spoke and read good English as one of his languages.

For more remarks, see my post about Hugh Eldridge’s reply to this letter.

Here’s what I’ll do to make this letter a good learning and teaching experience:

- I line up the published Chinuk Wawa in bold with its English translation ‘in quotation marks’, as close to word-for-word as is possible.

- In italics I’m also throwing in Grand Ronde Dictionary spellings for reference — as that is currently the best and most-used authority on the language — plus an English word-by-word gloss.

- (In parentheses) I’m putting my own best translation of what the Chinuk Wawa actually says.

- Bracketed numbers [1], [2], etc. refer to footnotes that I’m adding at the bottom.

Heading:

LA CONNER, WASH., December 20, 1928.

[to] Mr. Hugh Eldridge,

Bellingham, Wash.Nika kloshe tilacum SchulOkset :

náyka ɬúsh tílixam SchulOkset:

my good friend SchulOkset:

‘My Good Friend Schul Okset [1]:’

(‘My good friend SchulOkset:’)

Paragraph 1:

Nika Delate sheem pe sick tumtum nika wake hyak keelapie tzum papah kopa

náyka drét shím pi sík-tə́mtəm náyka wík áyáq k̓ílapay-t’sə́m-pípa kʰapa

I really ashamed and hurt-heart I not quickly return-write-paper to

‘I am your good friend but I felt bad because I did not answer your letter sooner.’

(‘I’m really ashamed and sad that I haven’t soon written back to’)mika,

máyka,

you,

…

(‘you,’)pe Klonass mika tum tum alta nika mitlite mesahche tumtum kopa mika.

pi t’ɬúnas máyka tə́mtəm álta náyka míɬayt masháchi tə́mtəm kʰapa máyka.

and maybe you think now I have hostile heart to you.

‘I guess you think I was sore at you.’

(‘and I reckon you’re thinking now I’ve got ill will towards you.’)

Kopa mika papah mika tikeh kumtux spose mitlite hiue chuck kulakula

kʰapa máyka pípa máyka tíki kə́mtəks (s)pus [2] míɬayt háyú tsə́qw-kə́ləkələ [3]

in your letter you want know if there.are many water-bird

‘In your letter you wanted to know if there was lots of ducks’

(‘In your letter you want to know whether there are lots of waterfowl’)kopa ocoke illahe, pe spose kahkwa mika hyak chaco yahkwa pe nesika

kʰapa úkuk íliʔi, pi (s)pus kákwa máyka áyáq cháku yakwá pi nsáyka

to this place, and if so you quickly come here and we

‘here and if there was you would come down and we’

(‘at this place, and if there are you’d come right over here and we’d’)konomoxt poh kulakula.

kʰanumákwst p̓ú kə́ləkələ.

together shoot birds.

‘would hunt them together.’

(‘shoot birds together.’)

Paragraph 2:

Nah ; SchulOkset, Alta ocoke illahe delate klahowyum, wake kahkwa ahncutty

ná [4], SchulOkset, álta úkuk íliʔi drét ɬax̣áwyam, wík kákwa ánqati

hey, SchulOkset, now this country really poor, not like previously

‘Say, Schul Okset, now this country is very poor—not like it was when there was’

(‘Hey, SchulOkset, now this country is really pitiful, not like it used to be,’)hyue kloshe muckamuck,

háyú ɬúsh mə́kʰmək,

a.lot good food,

‘plenty of good food.’

(‘(with) lots of good food.’)alta halo mowich, kulakula, pish pe konaway iktah kloshe kopa konoaway kah

álta hílu máwich, kə́ləkələ, písh [5] pi kánawi íkta ɬúsh kʰapa kánawi-qʰá

now no deer, bird, fish and every thing good in every-where

‘Now there is none—no ducks or deer or fish—everything good that was all around’

(‘Now there are no deer, birds, fish or anything that was good all over the place’)ahncutty nesika illahe.

ánqati nsáyka íliʔi.

[that was] [6] previously our country.

‘our country is gone.’

(‘our old country.’)[page] 31

Chee Chahco T’kope tilacum klaska delate mamook klahowyum ocoke illahe.

chxí-cháku tk̓úp-tílixam ɬáska drét mámuk-ɬax̣áwyam úkuk íliʔi.

newly-arrived white-people they really make-poor this country

‘The white people that have come into the country lately‘

(‘The white newcomers have really wrecked this country.’)Klaska delate kumtux konway iktah mamook spose isskum ahncutty kloshe

ɬáska drét kə́mtəks kánawi íkta mámuk (s)pus ískam ánqati ɬúsh

they really know every kind work to get oldtime good

‘have done everything they can to get‘

(‘They’re clever about all kinds of ways to get the oldtime good’)muckamuck pe alta delate chahco halo kopa konway kah illahe.

mə́kʰmək pi álta drét cháku-hílu Ø [7] kʰapa kánawi-qʰá íliʔi.

food and now really become-none it in every-where place.

‘all the good places where there are things that are good to eat and there is nothing left for the rest of us.‘

(‘food and now it’s gone from all over the country.’)Allta hyue T’kope tilacum klaska isskum kah ahncutty kloshe illahe pe kah

álta háyú tk̓úp-tílixam ɬáska ískam qʰá ánqati Ø [8] ɬúsh íliʔi pi qʰá

now many white-people they get where formerly were good places and where

‘They have all the good duck grounds’

(‘Now a lot of white people have taken where there used to be good places and where’)kwonesum hyue kulakula pe klaska potlatch lawin “Oats,” lebley “wheat”

kwánsəm háyú kə́ləkələ pi ɬáska pálach Ø [9] lawén “oats”, ləbléy [10] “wheat”

always many bird and they give them oats, wheat

‘and they feed the ducks lots of oats and wheat’

(‘there are always lots of birds and they give them oats (and) wheat’)spose kulakula chaco pe muckamuck, kahkwa klaska mamook memaloose

(s)pus kə́ləkələ cháku pi mə́kʰmək, kákwa ɬáska mámuk-míməlust

so.that bird come and eat, that.way they make-die

‘and have gun clubs so when the ducks come to feed on the oats and wheat they kill’

(‘so the birds will come and eat, so they can kill’)hiue kulakula, Boston wawa klaska name “gun Club.”

háyú kə́ləkələ, bástən wáwa ɬáska ním “gun club”

many bird, Americans say their name “gun club”

‘great quantities of them’

(‘lots of birds; the Americans call them “gun clubs”.’)Klahowyum man kahkwa nika wake konse nika mamook memaloose ikt

ɬax̣áwyam mán kákwa náyka wík-qʰánchi náyka mámuk-míməlust íxt

poor man like me not-ever I make-die one

‘so if you haven’t any money to join a gun club you can’t kill a single’

(‘A poor man like me, I can never kill a single’)kulakula kopa konway ikt cole, halo nika chickamin spose cooley konomoxt

kə́ləkələ kʰapa kánawi-íxt kʰúl, hílu náyka chíkʰəmin (s)pus kúli kʰanumákwst

bird in any-single year, none my money to go.around with

‘duck in a whole year.’

(‘bird in any year, I don’t have money to go around with’)

Gun-club.

“gun club”

“gun club”

…

(‘a “gun club”.’)

Paragraph 3:

Nah six, klonass spose ahncutty Tyee SchulOkset mitlite ocoke sun pe yaka

ná shíksh, t’ɬúnas (s)pus ánqati táyi SchulOkset míɬayt úkuk sán pi yáka

hey friend, maybe if oldtime chief SchulOkset be.present this day and he

‘Say friend, if your namesake, Chief Schul Okset, was here now and’

(‘Hey friend, I reckon if old chief SchulOkset was here today and he’)nanich konway iktah kloshe muckamuck chahco halo yaka delate sollicks

nánich kánawi íkta ɬúsh mə́kʰmək cháku-hílu yáka drét sáliks

see every kind good food become-none he really angry

‘saw that all the good food that used to be here was gone, he would be very mad’

(‘saw every kind of good food disappearing he’d be really angry’)kopa konway chee chahco T’kope tilacum pe klonass yaka mamook halo

kʰapa kánawi chxí-cháku tk̓úp-tílixam pi t’ɬúnas yáka mámuk-hílu

at all newly-arrived white-people and maybe he make-none

‘at the white people that had killed it off and no doubt would make’

(‘at all the white newcomers and I reckon he’d annihilate’)konway klaska. Ahncutty ocoke hyas Tyee SchulOkset yahka delate huloima

kánawi ɬáska. ánqati úkuk háyásh táyi SchulOkset yáka drét x̣lúyma

all them. formerly this great chief SchulOkset he really different

‘them all hard to find. Schul Okset was different’

(‘them all. In the old days that great chief SchulOkset was really unique’)kopa konway tilacum spose yaka klap sollicks tumtum yaka hyak mamook

kʰapa kánawi tílixam (s)pus yáka t’ɬáp sáliks-tə́mtəm yáka áyáq mámuk-

from all people when he get angry-heart he quickly make-

‘from all others ; when he got mad he’

(‘among everybody; when he got angry he’d straightaway’)memaloose delate hyue tilacum. Halo yaka isskum musket “gun” spose

míməlust drét háyú tílixam. hílu yáka ískam mə́skit “gun” (s)pus

die really many people, none he take gun “gun” in.order.to

‘killed everybody he was mad at.’

(‘kill a whole lot of people. He wouldn’t get a gun to’)memaloose tilacum halo opitkeg pe

míməlust tílixam hílu úpt’ɬiki pi

kill people none bow and

‘He didn’t use a gun or a bow and’

(‘kill people with, no bow and’)klietan “bow and arrow,” halo opitsah “knife.” Kopet ocoke hyas mamook stone

kaláytən “bow and arrow”, hílu úptsax̣ “knife”. kʰə́pit úkuk háyásh-mámuk [11] stún

arrow “bow and arrow”, none knife “knife”. only that heavy-duty stone

‘arrow or a knife ; he had his magic club’

(‘arrow, no knife. Just that heavy-duty stone tool’)ahncutty tamahanwis potlatch yaka spose mamook mamaloose

ánqati t̓əmánəwas pálach yáka (s)pus mámuk-mímlus

long.ago medicine.man give him in.order.to make-die

‘and he cast a tamahnawis spell on this great war club when he wanted to kill’

(‘that a medicine man gave him long ago for killing’)tilacum. Nawitke ocoke Tyee SchulOkset ahncutty yaka delate skookum tyee

tílixam. nawítka úkuk táyi SchulOkset ánqati yáka drét skúkum táyi

people. indeed that chief SchulOkset long.ago he really powerful chief

‘a lot of enemies. Yes, that great Chief Schul Okset was a great man—’

(‘people. It’s a fact, that great chief SchulOkset used to be a really powerful chief’)kopa konway tyee, delate kahkwa George Washington tolo hyas illahe, pe

kʰapa kánawi táyi, drét kákwa George Washington túlu háyásh íliʔi, pi

among all chief, really like George Washington beat great country, and

‘greater than any other chief. He was like George Washington, who won a great country and’

(‘among all chiefs, just like George Washington beat a great country, and’)kahkwa alta nesike kwonesum youlth tumtum kopa ocoke illahe.

kákwa álta nsáyka kwánsəm yútɬiɬ-tə́mtəm kʰapa úkuk íliʔi.

so now we always glad-heart about this country.

‘now we are always proud that he did so.’

(‘so now we remain proud of this country.’)

Paragraph 4:

Nike tumtum elip kloshe spose nika alta kopet hiue wawa kopa ocoke papah,

náyka tə́mtəm íləp-ɬúsh (s)pus náyka álta kʰə́pit hayu-wáwa kʰapa úkuk pípa,

I think more-good if I now stop going.on-talk in this letter.

‘I think I had better quit writing so much.’

(‘I think it’s best if now I stop chatting in this letter,’)

nika wake tikeh spose mika klap sick latate kopa nika hiue wawa.

náyka wík tíki (s)pus máyka t’ɬáp sík-latét kʰapa náyka hayu-wáwa.

I not want so.that you get hurt-head from my going.on-talk.

‘I don’t want you to get a headache reading all I have got to say.’

(‘I don’t want you to get a headache from my chatting.’)

Paragraph 5:

Nika delate youlth spose nika nanich mika chahco yahkwa pe nesika hiue wawa

náyka drét yútɬiɬ (s)pus náyka nánich máyka cháku yakwá pi nsáyka hayu-wáwa

I really glad if I see you come here and we going.on-talk

‘I would be very glad to see you and to talk over’

(‘I’ll be glad if I see you come here and we chat’)kopa konway iktah delate ahncutty. Nika tenas kwass spose nika wawa kloshe

kʰapa kánawi-íkta drét ánqati. náyka tənəs-k̓wás (s)pus náyka wáwa ɬúsh

about every-thing really oldtime, I a.little-afraid if I say good

‘old times but I am a little afraid if I asked you to’

(‘about all the oldtime things. I’m leery that if I say’)mika chahco pe poh kulakula pe klonass halo ikt kulakula mika nanich

máyka cháku pi p̓ú kə́ləkələ pi t’ɬúnas hílu íxt kə́ləkələ máyka nánich

you come and shoot bird and maybe none single bird you see

‘come down and shoot ducks with me that we wouldn’t see a single duck down’

(‘you should come and shoot birds then you maybe won’t see a single bird’)yahkwa.

yakwá.

here.

‘here.’

(‘here.’)

Paragraph 6:

Klahowya Schul Okset nika tickie spose mika hiyu hehee alup hias

ɬax̣áwya(m) SchulOkset náyka tíki (s)pus máyka hayu-híhi Ø [12] íləp-háyásh-

goodbye SchulOkset I want so.that you going.on-enjoying on more-big-

‘Good bye Schul Okset and I hope you have a Merry Christmas’

(‘Goodbye SchulOkset, I hope you’ll have a good time at Christmas’)Sunday pe delate youelt tumtum copa chee cold Sunday.

sánti [13] pi drét yútɬiɬ-tə́mtəm kʰapa chxí-kʰúl-sánti.

holiday and really glad-heart on new-year holiday.

‘and a Happy New Year.’

(‘and be really happy on New Year’s Day.’)WILLIE MCCLUSKEY.

Notes:

[1] SchulOkset: a Salish hereditary name applied to Hugh Eldridge, formerly held by a chief, as noted elsewhere in Mr. McCluskey’s letter. It closely resembles the name of a “Lummi sub-chief” who signed the Treaty of Point Elliott, “Ch-lok-suts“.

[2] (s)pus: the usual version at Grand Ronde is pus, but it more northerly coastal areas spus was more common.

[3] tsə́qw-kə́ləkələ: literally ‘water-bird’ this term is a new discovery. If it was understood in northwestern Washington state as meaning duck, this is another clue to dialect differences in Chinuk Wawa. At Grand Ronde, ‘duck’ is qʰwéx̣-qʰwex̣.

[4] ná: as an interjection to get somebody’s attention, this is not recorded at Grand Ronde, but it’s well-known elsewhere in Chinuk Wawa.

[5] písh: this synonym for ‘fish’ is not recorded at Grand Ronde, where sámən is the generic word.

[6] [that was]: here I’m pointing out a relative clause, a structure that Chinuk Wawa doesn’t mark with any spoken word but instead with the intonation of the voice. See the next few footnotes.

[7] Ø: this is another of the several “unspoken” typical fluent-speaker structures in Mr. McCluskey’s Chinuk Wawa. Where some English-speaking Jargon users would naively say yaka for a third-person nonhuman subject ‘it’, we have here a null pronoun contrasting with the human/animate yaka.

[8] Ø: a null existential copula ‘there is’.

[9] Ø: a null third-person nonhuman object ‘it’.

[10] ləbléy: the Grand Ronde word for ‘wheat’ is saplél which also means ‘flour, bread’.

[11] háyásh-mámuk: this is a newly discovered expression but it closely parallels one that’s well-documented in British Columbia, til mamuk ‘heavy work; violence’.

[12] Ø: a null preposition, typical of fluent speakers in expressions of a point in time.

[13] sánti: in this meaning ‘holiday’, not documented at Grand Ronde, but well-known elsewhere.

This was awesome man. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

hayu masi. wik-lili pi chako kilapai-pipa kopa ukuk!

LikeLike

Pingback: Crowdsourcing challenge (Swinomish edition): The finale | Chinook Jargon

You mention that the “Na” attention getter isn’t mentioned in the GR dictionary. But isn’t this na, which I’ve also seen as “how na” a mild derivative or at least natural cognate with “aná”? Ana, ala, are listed in both the GR usage and regional supplement sections, and certainly the latter in Gibbs.

“Opitkeg” – recently a friend and I were discussing the predominant final /x/ or /x̣/ obvious in much older CW vocabulary of this sort, rendered there by “h” or “g” or “gh”. That is, I infer a shift from, for instance, “t’qex” to “tiki”. Judging from the dictionaries, unstressed final syllable x seems to lose out circa 1880… do you reckon? Was this a regional variation, or something mostly dropped across all CW at such a point due to shortening and evolution away from glottal breath, a la chxi -> chi.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also to note in this x vein: possible qax rendered as kah, here, rather than GR standard qa.

And when the writer is talking about the anqati tayi Schulokset, he makes the yaka/yaxka emphatic distinction by use of an h in yahka after yaka in a previous clause, which you didn’t mark in your GR transcription.

Of course, they played hard and fast with the orthography back in the day… but I’m wondering if and how these x sounds are being noted here, and how we might more reliably read them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m doubting this writer had the yaka/yaxka distinction. I haven’t noticed evidence for it outside of the Grand Ronde zone…so I take any variance in his spellings as just charmingly fast & loose informal orthography 🙂

LikeLike

It does pique my interest how one can decide on certain readings, especially when more native phonemes are possibly to be derived. If there is no or scant material to make philological comparisons from original languages, how do you decide h as silent or x?

I’m looking at the rare lexeme “la-lah” in Shaw, glossed as to cheat. Given the “fast and loose” unorthography back then, is this lala or lalax, and how would we reliably come to know? Shaw uses the gh digraph elsewhere, but not seemingly consistently.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very intelligent questions once again. Briefly: you have to consider all possibilities. If you find a word written only once, and with a vowel plus “h” at the end of it, you check potential Native source forms that end in vowel and those that end in a fricative. Lots of work…

LikeLike

Your suggestion is compelling — that the interjection ná ‘hey you’ may be related to the interjection aná ‘oh my’. You deserve all credit for this! It can be hard to demonstrate etymological connections among outlier words such as interjections, for example because they have such similar forms across the Pacific Northwest’s unrelated languages. But your notion makes intuitive sense to me.

As for the loss of final /x/-type sound from the word that became tíki, I suspect that process was pretty much completed before 1880 but someone needs to take the time to look at the details. I tend to see it as having been a process of English-language influence, both in terms of simplifying syllable structure and shifting from Aboriginal to European sounds, Another nice little linguistics paper / dictionary entry waiting to be written 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I felt early on the aná exclamations were also related to the interrogative na as well as this interjection. Do you happen to know if there is a potentially antecedent grammatical particle, perhaps, in any of the native source languages in the Chinukwawa sprachraum?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Future research”, for whoever gets to it first. My gut feeling is that no such antecedent will be found. But this remains to be checked.

LikeLike

Also, pi siktumtum naika pos nai haiyu-wawa kakwá, I’m a bit surprised to read the s in spose being commonly pronounced in the north, at least in native communities. I keep reading conflicting conclusions regarding this in pus/pos… that it was an artifact of the “suppose” folk etymology never actually pronounced, or that it was introduced possibly on that misidentification on the mouths of some Anglo speakers of CW, but not said in native peoples’ CW dialects. Please clarify this history?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very briefly, I tend to chalk up the initial “s” in spos to English-language influence, which was markedly more intense later / in northern areas than it had been earlier / in southern areas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Early 1850s: ‘Christmas’ & ‘eat crow’ humor on Shoalwater Bay | Chinook Jargon