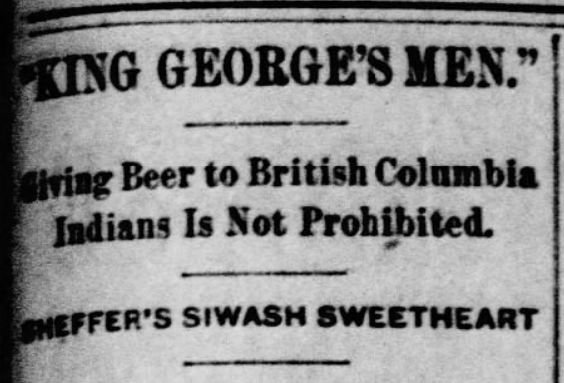

1894, WA: A judge who knows Chinuk Wawa knows “King George’s Men” is gender-neutral

Chinook Jargon was crucial in one judge’s decision in 1894.

The newspaper reporter of the following fouled up a historical detail: the American Fur Company played a pretty small role in how things got to be the way they were, compared with previous maritime fur traders and the succeeding Hudson Bay Company.

But assuming the reporting is accurate, Judge Emery (any connection with Eva Emery Dye?) understood kʰinchóch-mán and bástən-mán, accurately, as not fundamentally gendered.

These Jargon phrases have long been conventionalized, almost as though each were a single word, denoting nationality more than gender.

That’s relatively easy to do in a language such as this one, which just plain lacks grammatical gender.

With this in mind, you can take in a kind of remarkable legal decision that was consistent with loopholes in the US laws of the time, and as racist as the wording of the following article.

H. W. Sheffer was given a hearing be-

fore United States Commissioner Emery

yesterday and acquitted on the charge of

giving beer to Indians. Sheffer, while

entertaining three siwash squaws in his

room in the Whitechapel district, sent out

for a kettle of beer, and they all got

gloriously drunk and were arrested. At

the trial yesterday Judge Emery discov-

ered that the Indians belonged in British

Columbia, and therefore Sheffer had not

violated the Federal statute, which pro-

vides that no one shall sell or give beer,

wine or liquor to Indians in charge of an

agent or belonging to a reservation, and

when not otherwise shown, an Indian is

assumed to belong to a reservation.

Judge Emery, during his twenty-one

years’ experience on Puget sound, has

become more or less acquainted with

siwash languages, customs and traits of

character, and it did not take him long,

when the squaws were put upon the stand,

to discover that they were “King George’s

men” and not “Boston men.” In the

olden time, when the first white traders

pierced the Northwestern wilderness in

search of furs, the Hudson Bay Company

proclaimed themselves to the natives as

King George’s men, and the traders of the

American Fur Company on the Columbia

river, whose headquarters were Boston,

habitually spoke of their superiors as Bos-

ton men. In course of time the In-

dians who attached themselves to the

interests of one company or other got

to calling themselves “King George’s

men” and “Boston men,” and to this

day this distinction is the one known as

separating the tribes north and south of

the boundary line. King George’s men

are a handsomer race of people than the

Boston men and also more amiable.

Among many of the tribes up there the

custom of tattooing the person prevails,

while it is unknown among the southern

tribes, and when the squaws told the judge

that their home was among King George’s

men judicial notice was taken of the cor-

roborative evidence furnished by their

tattooing.

— “King George’s Men”, in the Seattle (WA) Post-Intelligencer of April 26, 1894, page 5, column 1