Reminiscences of 1848 on Puget Sound

Here’s an early western Washington settler’s recollection of his first trip “down” Puget Sound — meaning northwards — in 1848, and of pretending not to understand Chinuk Wawa once.

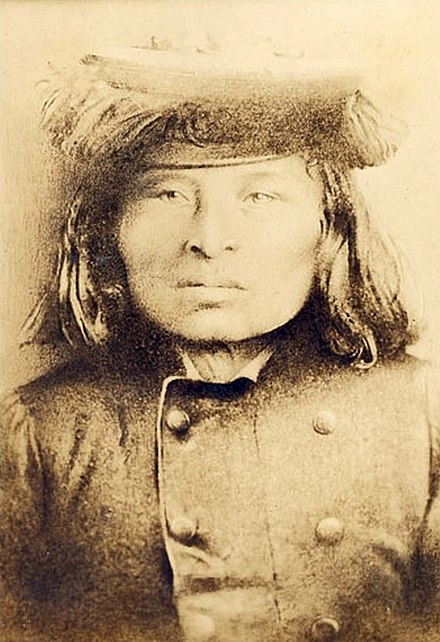

paƛ̕adib/Patkanam/Pat Kanim, circa 1855 (image credit: Wikipedia)

When Rabbeson and his group of Whites leave Tumwater and explore Hood Canal in the spring of 1848, the signs of Chinook Jargon are immediate. They hire Indigenous people to portage their “canoe and other traps” (i.e. general equipment), presumably using the Jargon.

And they find a “large camp” of Native people near modern Union City, “many of whom for the first time looked upon the face of a white man”. Nonetheless, some of these folks could communicate well with Rabbeson’s group. Seeing the large, powerfully built A.D. Carnefix left behind to tend camp, the chief of the Skokomish tribe concluded that he was a slave, and offered to buy him. “[W.] Glasgow’s woman” — almost certainly a Lushootseed Salish-speaking Native — disliking Carnefix, informed him that he probably would be bought, no matter how high a price the Whites asked, so Carnefix immediately left for Tumwater on foot, and the group now “purchased an Indian slave”.

The explorers find large numbers of Indigenous people everywhere they go on Hood Canal, up to Port Townsend, and over to Whidbey Island. At the site of a possibly abandoned Catholic mission, at Ebey’s Landing, the group build Glasgow a cabin.

There’s a gathering of maybe 8,000 Natives at Penn’s Cove on Whidbey Island, and the explorers ask about its purpose — again we see Chinook Jargon had to have been used. They’re told there’s to be a “grand hunt”, which they indeed witness, and a “big talk”. Glasgow’s woman (again referred to in this way that suggests she wasn’t White) advises the explorers to lay low for a few days during much of this. She acts as their interpreter during the meeting of tribes from around the Sound, including the Snohomish, S’Klallam, and Duwamish. As related by her, the words of the chiefs such as Patkanam have harsh criticism of, and threats of violence against, the Hudsons Bay Company and the rapidly increasing American Settlers. (The Jargon phrases “King George men” and “Boston men” are both used.) Chief John Taylor urges killing & driving out the Whites, who will soon outnumber Indigenous people; the latter would then be shipped out on what are called in Chinuk Wawa ” ‘fire-ships’ (steamboats) to some distant country where the sun never shone and there left to die, and what few Indians escaped their fate would be to be [SIC] made slaves.” This is the much-feared Polaklie Illahee belief.

Gray Head of the Tumwater tribe disagrees, saying the tribes of Patkanam, John Taylor, etc. had historically raided and harmed the Nisqually and other southern Sound tribes, and that the Bostons had brought peace. The unnamed “chief of the Duwamish tribe”, who I guess is Seattle himself, offers to protect the southern Puget Sound tribes, but the Nisqually and [Upper] Chehalis present reject this idea. The meeting appears headed to violence, thought likely to start with killing Glasgow’s & Rabbeson’s group of non-Natives, who accordingly steal a canoe {!} and escape.

Having gotten away as far as [Port] Blakely, the canoe is “stove”, that is, it gets an unfixable hole. The group is stranded, and with great trepidation they hail a passing canoe of Natives. “When they came ashore we pretended to understand but little Chinook. By signs and a few Chinook words we gave them to understand that we wanted to go to Fort Nisqually, and that we would give them our two blankets to take us there.” Both White men “being somewhat conversant with their language” (we’ve sometimes seen that Puget Sound Settlers picked up a fair bit of Dxʷləšucid/Lushootseed as well as Chinuk Wawa), they found that the canoeists were Duwamish who seemingly wanted to take them to Gig Harbor and “make good Bostons of us” — kill them. Further machinations occur, and the Natives are ordered under gunpoint to take the Whites where they want to go.

All of the above are in “Pioneer Reminiscences: A Trip on the Sound in Olden Times”, by A.B. RABBESON, in the Olympia (WT) Washington Standard of June 11, 1886, page 1, columns 2-4.

Although this frontier-era article quotes very little Chinook Jargon directly, it gives us a very clear picture of the language environment on Puget Sound in the 1840s. CJ wasn’t yet very widely known among tribal people there. Most of them spoke or could understand Lushootseed. Settlers, being still a powerless minority, accommodated Native people linguistically, using either the Jargon or Lushootseed to the best of their ability. About ten years later, when the 1858 British Columbia gold rushes happened, the long predicted large numbers of non-Native people showed up, and Chinuk Wawa rapidly became the most commonly known language until English, soon after, came to dominate.

Bonus fact:

The rendering of that Native leader’s Lushootseed name paƛ̕adib as “Pat Kanim” by Settlers suggests that they had a hard time saying it accurately.

If it helps you, I’ll spell it in Grand Ronde style: pat’ɬadib; in the era we’re talking about, it would’ve still been pronounced more like pat’ɬanim.

It looks like Settlers re-interpreted this into the English-language first name Pat, and the Chinook Jargon word for ‘canoe’, which they often spelled as Kanim or Canim.

No connection with John Canoe, at last report!