“Skookum papers” and Capilano in Robert Burnaby’s letters

Thanks to Alex Code for pointing out a very interesting source of info on frontier-era BC history!

It’s the book “Land of promise: Robert Burnaby’s letters from colonial British Columbia, 1858-1863” (Burnaby, BC: City of Burnaby, 2002). (Read it for free at that link.)

Robert Burnaby was born in Leicestershire, England; he lived from 1828 to 1878. He came to British Columbia for the Fraser River gold rush of 1858, and stayed until 1873. He was in BC early enough that people still referred to Queensborough (a name we also find in northern-dialect Chinook Jargon) instead of the later (New) Westminster — see page 21 of this book. (Fun note on page 84: “If they had called it Canoe Westminster we could better understand”!) He had dealings with lots of the major players in the history books, such as Colonel Moody, Father Demers, Governor Douglas, Judge Begbie, Judge Crease, and so on.

The major city of Burnaby, in the Vancouver area, is named for him.

Burnaby’s letters from British Columbia, mostly addressed to his mother and brother back home, begin on page 58 of this book. He’s a correspondent who has real literate style and liveliness.

Page 59 —

In Victoria, BC, just about the only town in the colony, an observation that explains Chinook Jargon’s lack of a word for “cents” until later — “A chap was selling apples which they were buying at a “bit” or 6d. a piece. You can get nothing under a bit which is the smallest recognized coin, all the reckoning is in dollars or bits even here as yet.

From page 61 onwards, we gather that BC is very thickly populated with Native people everywhere Burnaby goes. Take note of this, please. It’s important for us to realize that British Columbia was totally dominated by Indigenous folks, and however numerous the newcomer gold rushers were, they were oriented towards getting help and information from the locals. Thus, the real usefulness of introducing the previously unknown Chinook Jargon to the province.

I’d also point out the arrival of 80 miners at once from Australia (page 63) — Lots of the non-Native gold rush folks had no previous experience of CJ, and would’ve spoken it imperfectly. This is a major explanatory factor for how the Jargon mutated back into a pidgin language, with a distinct set of grammar rules, in the north.

Like other British immigrants to the region, Burnaby frequently marvels at how “Yankees” talk. He points out USA habits of greeting, such “Let’s liquor” and “Well! Take a drink?” The majority of the gold rush era’s newcomers were Americans, or people like the so-called “Sydney Ducks”, arrivals from Australia. The great majority of women available to socialize and dance with, etc., were Indigenous. (Page 65.) Lots of the gold seekers came via California, so there’s discussion of “Californian idiom” (page 69 etc.).

Page 67, an appearance of Métis/Canadian French, which we also know as “French of the Mountains“, the long-established intercultural language of interior BC until Chinuk Wawa showed up:

Pages 71-72, in March of 1859, perhaps the first direct account by Burnaby of Chinook Jargon being used, and it’s with lower Fraser River Indigenous people:

King George men = kinchóch-mán = ‘British people’; kloosh tum-tum = łúsh tə́mtəm = ‘good heart, good feelings’.

Page 73, still March of 1859 & still in the Queensborough area: more CJ, misread by the editors of the book —

![]()

Hyass taitu = háyás táyí = ‘big chief; major chief’.

From the same letter, on page 74 —

![]()

Muck-a-muck = mə́kʰmək = ‘food’.

We can see how Burnaby consciously sees Chinook Jargon as a Native people’s language.

Page 76 of the same letter discussed Presse, a seasoned voyageur canoeman (along with Native rowers) in this group led by Col. Moody; Presse sings “Canadian French songs” and regales the newcomers with lots of anecdotes of his life.

Page 80: the stern-wheel boat Enterprise

Page 96, in June of 1859, on the lower Fraser River:

Last Saturday I started on a short exploring expedition if you will

look at a map of the Fraser, you will see a point where it forks, one arm

running northwards directly to the sea – just above this fork our town is

built or rather building; Mr. Skinner of Vancouver Island and a merchant

here named Holbrook took a canoe with me about 5 o’clock in the even-

ing. My boy the immortal Flux [apparently a diarrhea joke!] ; a young Canadian boy as interpreter and

four Indians, one the great chief or Tyhee of the river, whose going with

me was a delicate compliment; off we went paddling down stream at a

famous pace; for the river is very high with floods and extremely rapid

now – the usual scenery that never palls all the way down – about 1/4 to

8 having gone about 12 miles we camped for the night in an old Indian

village long deserted, where had been a potato patch, now growing net-

tles 4 feet high, and wild roses, berries and rank vegetation of all kinds.

Page 97, from the same jaunt, an encounter with “Kapeland”, who Alex Code, I think rightly, connects with the better-known spelling “Capilano” = qiyǝplenǝxʷ, likely at Musqueam. Alex points out that this indicates the existence of skookum papers or teapot as early as the 1820s…

Out on the grass lay a large stone for which they had a great reverence

– you could just discern it had been rudely cut sometime or other into

the shape of a head, and our natives said it was done “long time ago”.

They now lead us through an intricate trail, thick with underbrush,

brambles and sticks about 3/4 of a mile down to the sea where a great

chief named Kapeland an “ole man Tyhee” has a village. He received us

gravely, ushered us into his Lodge where his squaws were making mats,

cooking fish or doing nothing; one was rocking a baby in a novel sort

of cradle, a pliant stick fastened into the ground and the cradle hanging

from it by a string, at the bottom of the cradle a string which the woman

held, and by giving an occasional pull, the brat was comfortably bobbed

up and down. Seated on his mats the dirty old chief solemnly opened a

box, and took out a roll of rags, which he unfolded in long lengths one

after another till he disclosed a paper package, this was only the first of

a series of covers, at last he came to a series of scraps of paper which he

handed out one by one for our perusal nor would he be satisfied till we

had seen all. They were testimonials from Tom Dick and Harry of no

value religiously preserved, some dating back nearly 30 years.

Ole man Tyhee = úl-mán táyí = ‘old chief’; ‘elder chief’.

Page 98, from another June 1859 letter:

The stern wheel steamer is in sight. Old Govr. Douglas has just been

overhauling my office and accounts and giving me “Molasses” whereby a

story. Once one of the H. Bay Co.’s servants came to him armed to the

teeth, to say that some Indians were in the store and would not “Clat-

tawa“, i.e. go, and asking for assistance to force them out. “Oh!” said the

old Governor “use no force Sir, use no force – Give them some Molasses,

Mr Mackay!” So when anyone is buttered up we call it Molasses.

Clattawa = łátwa = ‘go’.

Page 101, “north channel of the Fraser”, July of 1859:

Our Indians feasted themselves on sturgeon’s head

“Hyass Kloosh muck a muck” as they call it, and curled themselves up in

their blankets betimes in the most compact form; nestling one against

the other and so close that you could not distinguish their forms.

Hyass kloosh muck a muck = hayas-łúsh mə́kʰmək = ‘very good food’.

On page 102, Burnaby refers to “the two Tyhees, Cochrane and self” 🙂 Tyhee= táyí = ‘chief’.

Page 104, same trip:

Our return was much the same as our progress, the Indians laughing,

talking and singing like children, stopping the Canoe to gather berries

“oleally” as they call them, fine wild raspberries, blackberries and blue

berries like a very large bilberry.

Oleally = úlali = ‘berry; berries’.

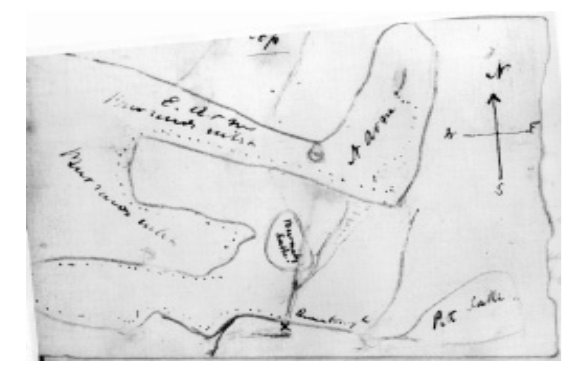

Page 106, a map drawn by Taintans, a local Indigenous chief:

Same page, August of 1859:

As I am now writing (in the most uncomfortable of positions with-

out table, lying on the mats and leaning on a roll of Blankets, a whim of

“My Novel” for a Desk) there is a group of the “Siwash” as they call the

natives, round the door of the tent, an old man munching some clams

(a species of escallop) which he has just cooked at our fire on a stick like

“Kabobs”, his mate a dirty wrinkled old hag, smoking a pipe and five

small “Klootchmen” or girls squatted about, they have great strings of

glass and brass beads round their necks, are exceedingly dirty, a dab or

two of red paint on their cheek and just down the parting of the hair, old

shawls and print dresses that might have lain by in a rag shop for years

without getting their present musty appearance.

Siwash = sáwash =‘Native’; klootchmen = łúchmən = ‘woman; women’.

Page 108:

The Indians behave most handsomely, they know that I am a Tyhee

who was with the “horse soldiers”, Tyhee “Conomody” as they called

him, and are on the best behaviour, they promise to shew us gold, but I

do not yet know whether to go or not, as it is a wilder and more unset-

tled place even than this, and here they could quietly dispose of us and

take themselves off very quickly.I had a hard days work yesterday, we started in a canoe at 10 o’clock,

two Indians, Moberley and myself, determined to get to the very head of

the Inlet, and not quite knowing how far it was. We only took a small

supply of “muck a muck“, as we made up our minds to return at night.

Up the Inlet, and round to the North in the same direction I went

before, between rocky steeps covered with wild looking pines, and said

to abound in deer and bears, wild ducks in abundance, at which we

shot enough, but they were too wild to hit, seals and porpoises, the one

showing his black bullet head above water, the other curving round and

showing his dorsal fins with a snort and down again, in numbers, ac-

cording to the Indians. I “Mameloosed” one of each; i.e. killed but as the

creatures always sink to the bottom unless mortally and instantaneously

shot, the fact is unsatisfactory if not problematical also; on we went,

paddle, paddle, staying for half an hour to lunch at 1 o’clock, on a nice

patch of grass by the side of a stream rushing from the rocks. We did

not reach the head of the inlet till five o’clock, a fine broad deep river,

as clear as crystal, runs in; through a wide valley; lying between the

ranges of mountains – this is a great place for salmon when they begin

to run. We went up it about a mile and a half, and very beautiful it was.

The banks fringed with beautiful ferns, the greenest of trees, the river

itself was very like a Scotch stream, clear, deep and swift, shallow in

the streams etc. It was 5 when we started back and we paddled steadily

on till 20 minutes past 10, when we got home well tired, a most lovely

paddle it was in the moonlight, shoals of salmon running down in the

clear depths, nothing stirring but a duck or two, and occasionally the

guttural greeting of a Siwash across the water when the light of his fire

was gleaming in the distance.

Tyhee = táyí = ‘chief’; muck a muck = mə́kʰmək = ‘food’; mameloose = míməlus = ‘to kill’ (well, in Chinook Jargon, it’s normally ‘to die’, but when borrowed into local English it works different).

Page 110, also August 1859:

The Indians fetch us any amount of Salmon, but tell

Tom (who must of course consider these letters addressed to him also,

as indeed they are to all the family) they do not rise at all to a fly and

will not be caught with rod line.The few lines I sent to tell you of our being all safe were hurried

off as a paragraph was in the papers that we were in the custody of the

natives etc. which happened on this wise. –The day after my last letter, we started off in a small canoe with two

Indians on an exploring trip, leaving two men in the Camp, and about

40 Indians about, all more or less armed. When we were in the middle

of the bay about 2 miles or so from shore, our natives left off paddling

and began a solemn “wa – wa” saying the crowd of Indians about were

very vexed, that the soldiers had taken two of their tribe and were going

to hang them for killing the man at the Mill, of which they were guilt-

less, and they were not in a state of “Kloosh tum-tum” with us, i.e. good

heart. You must know that every thing is ascribed to the “tum tum“;

if a “Siwash” dies it is of a sick tum tum – if he is in love ditto – if he is

friendly his tum tum is good to you and the reverse if otherwise.Now the native creed is a simple one, if one of them is unjustly killed

by a white man, all they want is another white man’s life to square the

account, it often happens that their grief may be assuaged by an equiva-

lent in blankets, but that is as it happens. The observations made were

therefore far from pleasant, so we told them to put about and take us

back, after some demur they did this. When we landed one of the men

came up, said he had been obliged to quit working, as the Indians were

crowding round him with stones etc. and wanted to take his shirt, and

the cook also had found a difficulty to keep them in order. They scowled

a bit at us, but we chaffed them and took no notice. After another long

“wa – wa” or palaver, we at last came to terms…

wa-wa = wáwa = ‘speech; conversation’; kloosh tum-tum = łúsh tə́mtəm = ‘good heart; good feelings’; tum tum = tə́mtəm = ‘heart’; Siwash = sáwash = ‘Native’; sick tum tum = sík-tə́mtəm = ‘sad(ness)’.

Page 112, in Burrard Inlet:

Our reason for this trip

was the Indians pointed out the water as not good to drink that it had

killed Indians etc. so we thought we might find Minerals but we found

them not ! and I drank some of the water to the horror and astonish-

ment of our guides, who said “King George Tahi! Skookum tum tum” i.e.

English chief, strong heart!

King George tahi skookum tum tum (when I repair the punctuation) = a full sentence, kinchóch táyí skúkum-tə́mtəm = ‘the British boss is strong-hearted’.

Page 131, in Victoria in early January 1860:

Thursday

we had a dance in Victoria, the half breed young ladies (Sitcums as they

are called) are very noisy: even to romping: they dance pretty well and

exhibit all the accomplishments of their betters; they know very well how

to shuffle off a partner they don’t care for, and secure the attention of a

favorite, and it is astonishing how they are “quite engaged” when some

people ask, and “only too happy” a moment after.

Sitcum would seem to be a newly discovered borrowing into local English of Chinook Jargon’s sítkum-sáwásh, ‘Métis’, literally ‘half-Native’.

Page 134, in February in Victoria:

We had a small excitement the other night though; just in the middle

of a rubber we heard a row amongst the Indians, and on going out found

their village (on the other side of the Harbour) in flames. Across the

Bridge we went to be sure, and you cannot fancy a stranger sight: these

houses are all cedar wood: thoroughly dry from having constant fires and

no chimney; they are mere uprights with boards against them thus- and

of course once in flames impossible to put out: to see the poor wretches

streaming out with their Blankets, pots and pans and other property and

crawling about the roof of the next Lodge ready to give the alarm on the

least symptom of danger: others pouring pans of water down the sides

which were smoking with the heat, talking and chattering to themselves

all the while: and looking with amazement when the Hook and Ladder

Company (of which more anon) came up, and cut off the communication

by at once demolishing the next Lodge. The old woman, such hags all

wrinkles and dirt, stood by wringing their hands and constantly repeat-

ing “clar how yer” – “clar how yer” which means “How do you do” – as

a token of their gratitude.

Clar how yer = łax̣áwya = ‘hello’, except that Burnaby surely knew it also means ‘poor; pitiful’ in describing a human being’s state.

Page 144, Victoria, June 1860 — a mention of a chief who is ” “hyon sollocks” i.e. (very angry),” in Burnaby’s unusual punctuation of it. The editors have misread the manuscript, which must have said hyou or hyas. Either way we have a northern-dialect CJ expression, háyú sáliks ‘very much angry’ / hayas-sáliks ‘very angry’.

Page 150 — November of 1860, apparently in the Hope, BC, area: “We saw a great “Mâche passisi” or Blanket feast and dance”… This is Chinook Jargon másh pásisi, ‘throwing blankets’. That’s a verbal clause in CJ, but Burnaby uses it like a noun phrase, much as Settlers adopted CJ pátlach (‘to give away’) as an English noun, potlatch.

Page 152, roughly the same area, some Chinese Pidgin English from a man racialized as “John Chinaman“:

Specimen of conversation with Chinaman: “Aha! John?

plenty Gold – plenty Dollars eh John!”. Chinaman: “Ah yah! No goodee!

four bittee, six bittee – all same, no goodee!”, and he grins and goes on

rocking away as before.