1778: Captain James Cook on the PNW coast — Definitely not Nootka Jargon, but… (Part 1: Narrative)

By definition, a first-contact report won’t contain a pidgin language, such as the so-called Nootka Jargon, nor Chinook Jargon, which we’ve been finding didn’t yet exist…

…This is because it takes a little time for two newly meeting cultures to accommodate one another by forming a mutually understood new language.

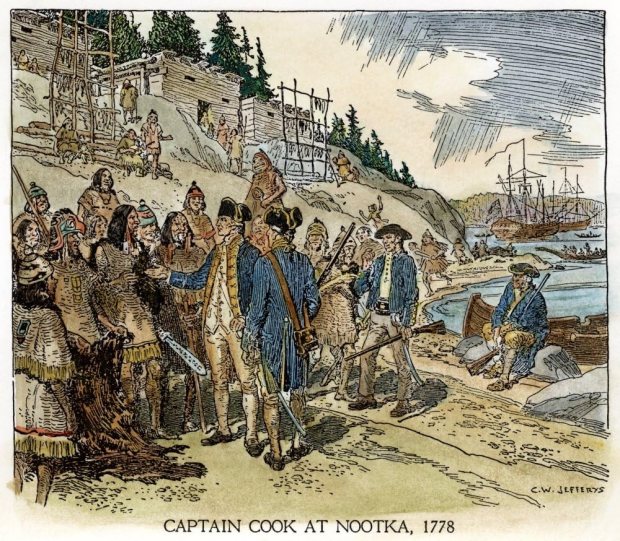

Captain Cook at Nootka, barely able to communicate, 1778 (image credit: Amazon)

Still, we should be mighty interested in how the first non-Indigenous visitors to Nuučaan̓uł land perceived & tried to speak the local language.

The visit by Captain James Cook’s ships Discovery and Resolution in 1778 gives us a pretty good baseline for understanding the strategies Native and Newcomer folks were using to try to communicate, when they had no previous experience of each other.

The journal of early contact that I’m examining is:

James Cook. 1821. “The Three Voyages of Captain James Cook Around the World“. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown.

Part 1: Data from the narrative text in Book 6.

Page 237 (March 6, 1778) — the expedition reaches the Oregon coast.

Page 244 (March 29, 1778) is the expedition’s first contact with Indigenous people of North America, at Hope Bay (Nootka Sound), and they are greeted by a traditional orator standing in one of the 3 canoes that come out; “we did not understand a word”. Others in the canoes then address the mariners, and one sings a song with the refrain haela. (Some visitors used this same ceremony upon arriving during the remainder of Cook’s visit.) More canoes keep arriving, at one point totalling 32 Native vessels. None of these Nuuchahnulths can be induced to come aboard the ships, but they are prepared and eager to trade various items, especially iron, which they appear to be well acquainted with; by the end of the visit, brass has become the prime item.

Page 248 (March 31st) has numerous Indigenous canoes around the ships all day long, trading many kinds of items including various furs, Native clothing, weapons, and handicrafts, and even brass and iron ornaments which the narrator sees as proof of at least indirect previous contact with non-Indigenous people. Also offered are human skulls and entire human hands, from people “which they made our people plainly understand they had eaten” (p. 249). The newcomers’ metal trade items are welcomed, but glass is disdained, and cloth is rejected.

On April 1st (p. 249), more than 100 canoes arrive, and people now willingly visit on board; it’s now found that they have no qualms about taking any iron item from the ships that they can carry away, without trading for it.

Page 252 has an incident of the locals suddenly arming themselves, causing the mariners to retreat to a safe spot with arms at the ready, but the cause of alarm is another Native group, “and our friends of the Sound, on observing our apprehensions, used their best endeavours to convince us” of this. Things get smoothed out between the two tribes, “but the strangers were not allowed to come along-side the ships, nor to have any trade or intercourse with us”. The mariners infer that the locals are intent on monopolizing trade with the Europeans.

The Native people often bring much-needed fish and oil to the ships (p. 254 et al.). Just a few pages into this narrative, it’s stated clearly that the ships’ people recognize individual Indigenous folks, and on page 254 for example, on the evening of April 11th, “we were visited by a tribe of natives whom we had never seen before”, and who are less overawed by any items on board.

Also, on the 18th of April, “a party of strangers” arrive in the cove but are apparently not allowed by the locals to visit the mariners (p. 255).

It’s also obvious to the visitors that local leaders are managing a thriving trade in European items with tribes who live farther away (p. 256), to get more of the Indigenous items that are guaranteed to be bought by Cook’s people.

On page 257, Cook goes ashore and visits a village, where everyone urges him to visit their home, which he accurately describes as a section within one of the big houses.

Visiting a village a bit farther away (page 258), Cook gets a chilly or mildly hostile reception from its chief, communicated “by expressive signs” — I wonder if this is due to his knowing he may be punished by the tribe that controls the European trade.

When he gets back to the ships (p. 259), he’s told of some different Native people who had visited and said by signs that they were from somewhere to the southeast — and who had a couple of silver spoons that they traded to Cook’s people! These people also seemed to already have more iron than the Nootka Sound locals.

On April 22nd (p. 260), a number of canoes, mostly strangers, arrive and conduct an elaborate version of the above-noted greeting ceremony, including song separated by “the word hooee! as a chorus”. After their visit, a party of mariners lands to cut grass for their shipboard livestock, but are immediately stopped by locals who insist “they must “makook;’ that is, must first buy it.” Cook also notes that earlier in the visit, the locals had insisted to his workmen that they pay for the wood and water they took aboard.

On page 263, as Cook’s ships are leaving on April 26th, “He [a local chief], and many others of his countrymen, importuned us much to pay them another visit, and, by way of encouragement, promised to lay in a good stock of skins.” The two chapters following this are general observations of Nuuchahnulth land and life.

On page 269, an unknown species of fur, perhaps a wildcat, is noted as being called wanshee by the locals.

On page 270 is the note that the locals called the Europeans’ goats eineetla, “most probably…their name for a young deer or fawn”. Page 290 is written history’s first mention of the Klumma, the decoratively carved house posts; two of these are cited by their individual names, Natchkoa and Matseeta.

Page 295 tells of two liliaceous (probably camas-like) roots, the mahkatte & koohquoppa, and a licorice-like root called aheita. The Nuuchahnulths very much disliked all of the foods and liquors offered by Cook’s people (p. 296).

The local version of a tomahawk is the taaweesh / tsuskeeah; another stone weapon is the seeaik (p. 297).

Page 303 informs us that the Nuuchahnulth people call “iron” seekemaile, “which name they also give to tin, and all white metals”; this is the ancestor of the Chinook Jargon word chíkʰəmin.

On the same page, we’re told that these tribes show no sign of previous contact with Europeans, or ships or guns, and that on Cook’s people’s arrival the locals inquired “by signs…if we meant to settle amongst them; and if we came as friends; signifying, at the same time, that they gave the wood and water freely, from friendship”. (Which sort of contradicts page 260!)

Pages 303-304, the locals “endeavour[ed] to make us sensible, that their arrows and spears could not penetrate the hide-dresses” (elk-skin “clemon” armor I reckon). Cook notes he was aware of Spanish visits to this region of the Northwest Coast before he left England, but that all signs indicate that the Spaniards had not yet visited Nootka Sound; the Nuuchahnulths must have instead been trading with those Native people who did have direct contact with those previous European visitors.

Page 305 notes that the local chiefs are known as Acweek.

In connection with the Klumma, it was not the case that “we could gain any information, as we had learned little more of the language, than to ask the names of things, without being able to hold any conversation with the natives, that might instruct us as to their institutions or traditions.” (P. 306.)

I’ll close this first of 2 installments looking at Captain Cook’s journal of time spent at Nootka with a couple of observations.

First, the make-do transcriptions of Nuuchahnulth into English spellings imply enormous unfamiliarity with that language; later visitors write local words in a more recognizable way. An example of this is Cook’s acweek translated as ‘chief’ versus Alexander Walker, 8 years later, with haweelkh for ‘friend’ — the modern Nuuchahnulth dictionary has ḥaw̓ił ‘chief’. On the one hand, Cook’s people seem to have been sharper at perceiving glottalized resonants such as w̓ than later visitors were, carefully recording this sound as cw versus later w. On the other hand, the voiceless lateral fricative ł puzzled the ears of Cook & crew, being approximated as k, versus later observers’ more evocative lkh, tl, etc. These first non-Native visitors remained on an uncertain footing throughout their visit.

Second, there are so many comments in the text saying & implying how hard it was to communicate reliably, that I’m very confident in pointing to Cook’s document in support of my assertion that there was no already existing pidgin / trade language along the Northwest Coast by 1778. Such a contact medium would’ve been quickly picked up by newcomers; we certainly see that happening with later-arriving mariners. Instead, in the documentation by successive Euro-American visitors, we see progression towards a pidginized, Nuuchahnulth-centred lingo.

Bonus facts:

Modern linguists analyze the Nuuchahnulth language(s) as part of the “Wakashan” family, a term which Captain Cook himself invented (p. 308): “Were I to affix a name to the people of Nootka, as a distinct nation, I would call them Wakashians, from the word wakash, which was very frequently in their mouths. It seemed to express applause, approbation, and friendship; for when they appeared to be satisfied, or well pleased with any thing they saw, or any incident that happened, they would, with one voice, call out Wakash! wakash!”

In this connection, I want to give respect to Cook’s observation that the people of south-central Alaska (Cook Inlet apparently) have a language differing from Nuuchahnulth, “but, like the others, they speak strongly and distinct, in words that seem like sentences” (p. 367). That’s a wonderful insight, foreshadowing later characterizations by linguists that these various groups’ languages are “polysynthetic“, often having many morphemes in one word.