1884: “Western rambles” and PNW folklore

Chinuk Wawa was invented by…

…the Jesuits?!

Portrait of Julia Kendall 😁 (image credit: Boyd Books)

Naw.

Late in the US frontier era, few folks any longer had firsthand knowledge of early Chinook Jargon times. The linguistic myths about this much-discussed language swirled all over the place.

We’ve seen, many times, the urban legend that “Chinook” was created by the Hudsons Bay Company to use in its fur trading business. There are other claims, such as today’s much more inaccurate one that it was Catholic priests who concocted the lingo.

Catholicism was generally seen as un-American by the largely Protestant and Northern European-derived Settler population. That’s the common thread with the idea of the (British, thus foreign) HBC being behind the Jargon.

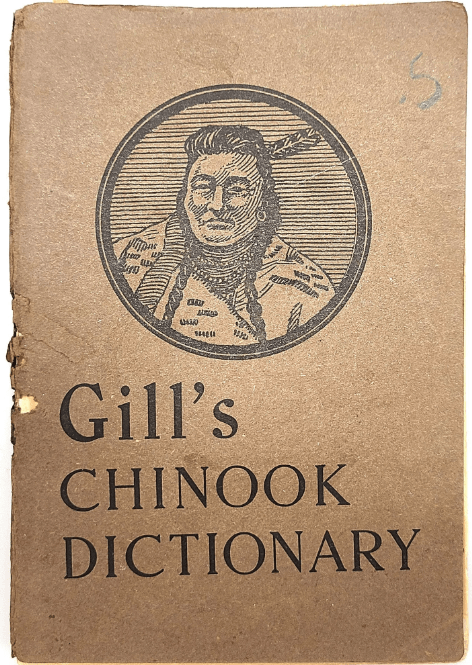

Here’s one person’s published letter home to Vermont about life in Washington Territory. Julia Kendall was writing from the important town of Walla Walla. She’s quoting from (and not crediting) the entries in, and the Preface to, one of the numerous editions of JK Gill’s best-selling Chinook Jargon dictionary!

Here she’s discussing that perennial source of curiosity, Native people.

I’ll add a number of comments after you read this excerpt, showing that it’s packed with Pacific Northwest folklore ideas:

They address the whites in a language

called Chinook; it was invented by

the Jesuits. If you wish to say good

morning, sir, you must say, clay-

hower-six ; cold water is cold chuck ;

eat is muck-a-muck ; Yankee is Bos-

ton man; music is tum-tum; amuse-

ment is he-he. It is said the first

attempt at publication of the trap-

pers’ and traders’ Indian jargon in

use among the coast and interior

tribe of the northwest was made in

1825, by a sailor who was captured

from the ship Boston, which was sur-

prised by the Indians at Nootka

sound, her captain and crew murder-

ed, the sailor who issued his adven-

tures under the title, “The Captive

in Nootka,” and later the “Traders’

Dictionary,” being the only survivor.

Several little books, mostly for trad-

ers’ uses, have been in this jargon.

A worthy missionary published quite

a number of hymns translated from

English in Chinook, which has been

the only use of the language in the

field of belle-letters. The native

language of the Indian is seldom

heard. The progressive English is

forcing its way even into the lodges

of the most savage tribes.

— from the Barton (VT) Orleans County Monitor of August 25, 1884, page 2, columns 4-5

Some notes on Ms. Kendall’s (JK Gill’s) claims about Chinuk Wawa:

- good morning, sir: clayhower-six (łax̣áwya síks, ‘hello friend’)

This idea of siks meaning ‘sir’ is something we’ve seen before, from Settlers only, based on the broad similarity of the two words. It appears to be Ms. Kendall’s addition to the Gill material. She’s also transposed the Jargon words into spellings of her own, which suggests some personal experience with this language. I’ve only found “clayhower” from one other writer. The remaining Jargon words and definitions are straight out of JK Gill:

- cold water: cold chuck (kʰúl chə́qw)

- eat: muck-a-muck (mə́kʰmək)

- Yankee: Boston man (bástən-mán, ‘American/White person’)

- music: tum-tum (actually tíntin; the newspaper’s typesetter must have misread her handwriting)

- amusement: he-he (híhi)

- The idea about “the first attempt to publish” any Chinook Jargon seems to be more PNW folklore, a fuzzy version of the facts — John R. Jewitt first published his captivity narrative in 1807, then in a more popular edition in 1815. There’s no indication of CJ in it; what we see reported there, as I’ve pointed out any number of times on this website, is “Nootka Jargon”, a pidginized version of the Nuučaan̓uł language of Vancouver Island. Jewitt never published a dictionary, although one of his publications includes a small word list.

- “Several little books” had indeed been published, but most of these Chinook Jargon dictionaries were more like tourist curios. It’s a contradiction in terms to imagine “traders” needing a published CJ dictionary, seeing as how the fur trade peaked before any commercially available dictionaries of the language were created. Not to mention that the great majority of fur trade workers were illiterate and not great speakers of English! (Most were Métis of recent eastern Canadian French & tribal heritage.)

- The “worthy missionary” is Myron Eells, about whose hymns I’m currently doing a mini-series on this website. But, despite the folklore about his work, Eells was explicitly not very interested in translating English-language hymns into Jargon. Instead, he took catchy popular tunes and created brand-new, simple, Chinuk Wawa lyrics with basic moral messages.

- The idea that the Indigenous languages were seldom heard in 1884 is mostly ridiculous. Some of these languages had declined by that time, typically in the first-contact areas such as Lower Chinookan lands. But most tribal languages were still the vehicle of everyday life. The truthful core in the folkloric claim of decline here is that, yes, from a Settler perspective, you heard tribal languages spoken less often — because by this time the Jargon, and increasingly English, were widely used for interethnic communication.