1882: Ave Maria in Chinuk Wawa — where did it come from?

There’s got to be a really interesting story behind this never-before-seen Chinuk Wawa text!

How is it that Father Aloys(ius)/Louis Pfister SJ, an accomplished Catholic missionary in China, came to contribute this text to an 1882 book that compiled the “Hail Mary” prayer in many languages?

I’d guess Pfister must have gotten this from somebody who had worked in the Pacific Northwest. But who? It remains to be discovered.

Maybe there are clues within this Jargon text in “Ave Maria: Sive Maria ab Angelo Variis Linguis…” Certainly it’s written in a French-style orthography, as we see from the vowels é, ï, & ou. Let’s see what else turns up:

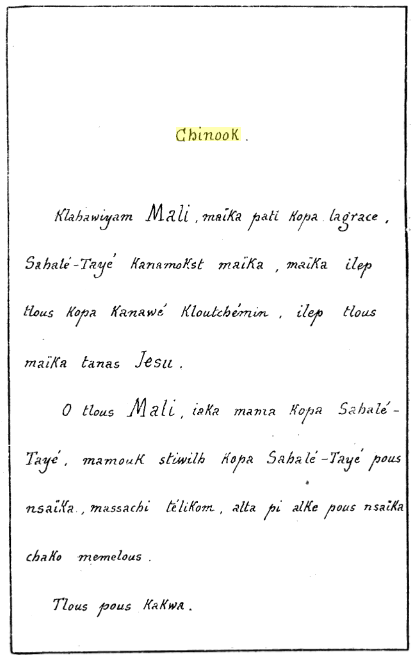

Klahawiyam Mali, maïka pati [sic] kopa lagrace, Sahalé-Tayé kanamokst maïka, maïka ilep tlous kopa kanawé kloutchémin, ilep tlous maïka tanas Jesu.

O tlous Mali, iaka mama kopa Sahalé-Tayé, mamouk stiwilh kopa Sahalé-Tayé pous nsaïka, massachi télikom, alta pi alke pous nsaïka chako memelous.

Tlous pous kakwa.

Diagnostic features in this 1882 translation include a weird mix: (1) patl kopa instead of more normal Southern Dialect/older patl to mean ‘full of’; (2) the Coast Salish-derived Northern Dialect stiwilh for ‘pray(er)’; (3) pous being used to express ‘for’ a noun (‘for us’), which is a distinctly Southern Dialect habit [when it’s not just a French priest mentally equating Jargon pus with French pour ‘for’]. On that last point, I’d also highlight “iaka mama kopa Sahalé-Tayé” as an unexpected translation of ‘mother of God’, as it has an unneeded kopa making it literally ‘his mother to God’ or ‘who is mother to God’. There’s also pous for ‘when’ we die, which is normal for the Northern Dialect. So the above translation sounds both Southern and Northern, and a little weird besides!

Compare this with the 1871 Demers, Blanchet, and St Onge publication’s version, which presumably traces back to circa 1838-1839 Fort Vancouver — a version that’s much more Grand Ronde-like (with its mank for ‘more’) and early Jargon-like (with its naha for ‘mother’ and kopa okuk for ‘then; when’ [seriously!]):

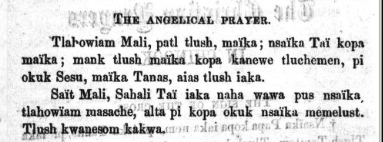

THE ANGELICAL PRAYER.

TlaHowiam Mali, patl tlush, maïka; nsaïka Taï kopa

maïka; mank tlush maïka kopa kanewe tluchemen, pi

okuk Sesu, maïka Tanas, aias tlush iaka.Saït Mali, Sahali Taï iaka naha wawa pus nsaika,

tlahowïam masache, alta pi kopa okuk nsaïka memelust.Tlush kwanesom kakwa.

And, from pages 45-46 of the 1896 “Chinook Manual” published at Kamloops, British Columbia, which we may assume goes back to 1854-1855 or so on the middle to lower Columbia River, courtesy of Bishop Paul Durieu: — This version is typical Northern Dialect, with its ilip for ‘more’, its Tlus (‘good’) for ‘saint; holy’; its styuil for ‘pray’; and its kah (‘where’) for ‘when’…the only Southernism / anachronism being the pus meaning ‘for’ us (you do get this sort of thing in Northern religious talk):

<Ave.> Klahawiam Mari, maika patl

lagras, ST mitlait kanamokst maika;

maika ilip tlus kopa kanawi kluchmin, pi

ilip tlus iaka, maika tanas Shisyu.Tlus Mari, ST iaka mama, styuil pus

nsaika, klahawiam tilikom, alta pi pus

k’o kah nsaika mimlus. Tlus pus kakwa.

Keeping this short, I’ll say that the 1882 Hail Mary seems like a perfect intermediate stage between the older (Southern) and newer (Northern Dialect) translations.

Maybe it was supplied by someone like E.C. Chirouse OMI, who had already been living and working on the coast for over 20 years?