Re-evaluating Boas’s 1888 “Chinook Songs” (Part 9)

Our case keeps solidifying…

…Franz Boas did us a huge favour by documenting all of these Chinuk Wawa songs that no one else thought to write down.

And, we can now add insights to deepen people’s understanding that “the Jargon” is a fluently expressive language, and that it had distinctive dialects such as this one that I’m calling “North Coast”.

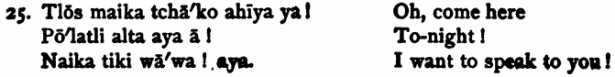

SONG #25:

Tlos maika tchako ahiya ya!

łúsh [1] máyka cháko ahiya ya!

good you come ahiya ya

‘Oh, come here’

DDR: ‘You should come (here), ahiya ya!’

Polatli alta aya a!

púlakʰli álta [2] aya a!

night/dark now aya a

‘To-night!’

DDR: ‘It’s evening now, aya a!’

Naika tiki wawa! aya.

náyka tíki wáwa! aya.

I want talk! aya

‘I want to speak to you!’

DDR: ‘I want to talk, aya!’

Comments on song #25:

łúsh [1] máyka cháko: I take the optional occurrence of łúsh in this dialect’s commands as softening them, so I’m translating this one with ‘should’. You could argue that Boas has reflected this with his added “Oh”.

púlakʰli álta [2] gets a revised translation by Boas in his 1933 paper on the Jargon: ‘It is dark now’.

Summary of song #25:

Both of my notes above are minor; Boas has effectively put the sense of the song into English. The difference between his ‘To-night’, and my (and his later) ‘It is dark/evening’ does make a scene-setting difference, though.

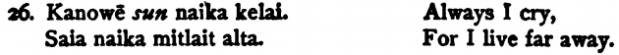

SONG #26:

Kanowe sun naika kelai.

kánawi sán náyka kʰiláy.

every/all day I cry.

‘Always I cry,’

DDR: ‘Every day I cry.’

Saia naika mitlait alta.

sayá náyka míłayt álta.

far I be.located now.

‘For I live far away.’

DDR: ‘It’s far away that I live now.’

Comments on song #26:

This lyric is a variation on song #2. See my comments there.

Summary of song #26:

It can be argued that the translation of these lyrics into English could be made more exact.

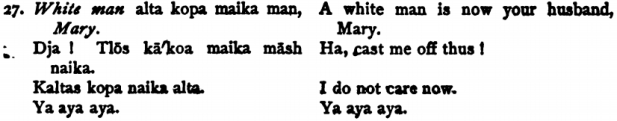

SONG #27:

White man alta [Ø] kopa maika man, Mary.

xwáyt-mán álta Ø [1] kʰupa máyka mán, méri.

white-man now exist for your man, Mary.

‘A white man is now your husband, Mary.’

DDR: ‘(So it’s) a white man now for your husband, Mary?’

Dja! Tlos kakoa maika mash naika.

dja! łúsh kákwa [2] máyka másh náyka.

dja! good thus you leave me.

‘Ha, cast me off thus!’

DDR: ‘Ha! Go ahead and leave me like that.’

Kaltas kopa naika alta.

kʰə́ltəs kʰupa náyka álta.

worthless to me now.

‘I do not care now.’

DDR: ‘I don’t care now.’

Ya aya aya.

ya aya aya.

ya aya aya.

‘Ya aya aya.’

DDR: ‘Ya aya aya.’

Comments on song #27:

xwáyt-mán álta Ø [1] — here I see the amply documented null (not pronounced) version of the Chinuk Wawa ‘be’ verb, since I analyze all freestanding main clauses in the language as having some kind of verb. By the way, < white man > is a known word of BC Jargon, occurring dozens of times in our data from the Kamloops region, for example; it’s more common than either < King George > or < Boston > there.

łúsh kákwa [2], as I’ve shown you in a couple of “Chinook Songs” already such as #10, is a kind of resigned/accepting ‘go ahead’ expression.

Summary of song #27:

Again we have an adequate translation by Boas, which nonetheless can be made more precise when we apply knowledge of Chinuk Wawa acquired since 1888.