Oregon: There & back in 1877 (& again)

Here’s someone who monetized his travelogues to beat the band!

Eventual Oregon State University founder Wallis Nash published not one but two books about his visits from England to Oregon. And he dedicated one of them, “Oregon: There and Back in 1877” (London: MacMillan and Co., 1878), to his friend and neighbor Charles Darwin — which could only have increased sales. Nash was financially quite sharp, and this trait extended to his writing activities.

During his 1877 trip, Nash made the acquaintance of a guide known as Kit Abbey, the “Kit” being “after his former mate and leader, Kit Carson, with whom he had lived and fought for many a year ‘on the plains’ ” (page 140). I hadn’t known much about 1851 pioneer Edwin Alden Abbey (lots of bio info at the link), but by coincidence it looks like he could expect a check in the mail from the US Congress when he got home from his jaunt in the woods with Nash:

from the Congressional Record

Having settled in Oregon while Whites were still a minority, Abbey spoke Chinook Jargon. He introduced Nash’s group to some “Yaquina Bay Indians” at a beachfront village, where the residents were so interested in Nash’s first sketching of them that headman Kaseeah and family (also aware of what audiences want) proposed changing into these “old-fashioned Indian” clothes for a second go:

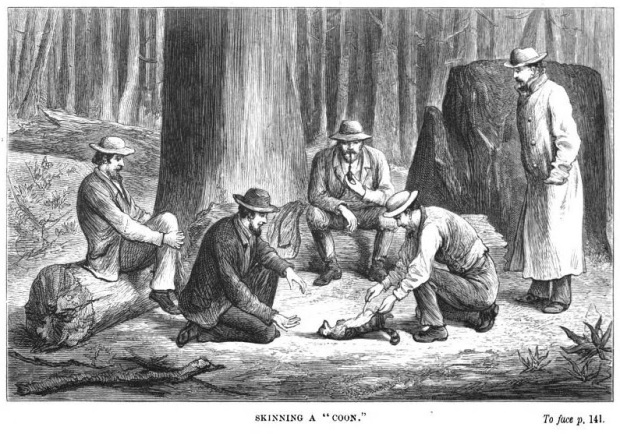

Kit Abbey also introduced his White visitors to some Coquelles, (Nash thinks) at the Siletz Indian Reservation:

When we had made our camp and lighted our fire some eight or ten of the Indians came round us. They all knew Kit Abbey, and a long and voluble Chinook conversation followed. (page 171)

There’s hardly any actual Jargon in Nash’s book, but his several attentive drawings of local people and scenes, his unusually respectful tone, and his trait of being a good listener, make this a pretty fine read for those interested in late-frontier Oregon. Here is his drawing of Kaseeah:

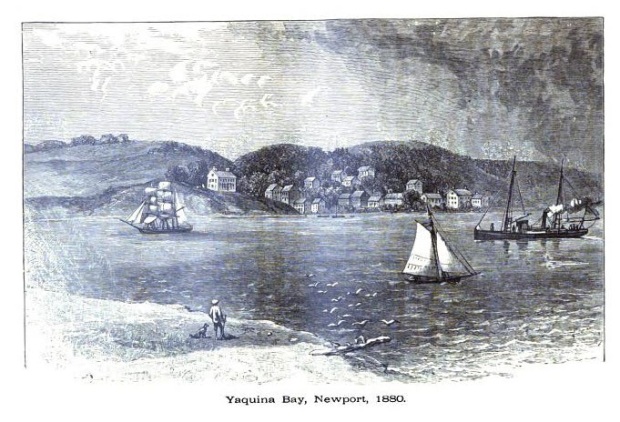

Now, by the same author: “Two Years in Oregon” (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1882 [second edition]). This volume is similarly sympathetic in tone; in fact, Nash wound up settling in Oregon and being an important citizen “booster”. But already Oregon seems noticeably more “settled” somehow. I’ll just briefly point out the Chinook stuff — albeit now tending to blend with a pidgin sort of English — for my present readership 🙂 Again Nash’s own astuteness equals what he attributes to the Native people he meets; at Siletz Reservation:

The voices cease as you come in sight, but your salutation, either in Chinook or English, is civilly returned, and a quick glance takes in at once your personal appearance and that of your horse, and every detail of your equipment. (pages 137-138)

And

There was a great variety of type apparent, for the remnants of thirteen tribes of the coast and Klamath and Rogue River Indians are collected on this reservation. Nearly all could speak a little, and understand more, English—and I think we could have got on quite as well without the help of the Indian interpreter, who turned our English into fluent Chinook. This man, named Adams, is an excellent fellow, well instructed, capable, civil, and, I believe, an earnest Christian man. The agent asked me to take the Bible class at the far end of the room, and soon I was the center of the observant eyes of a dozen Indian men of all ages. Certain of them were friends of mine. Old Galeese Creek Jem, a little fellow about five feet high, with a broad face and a pair of twinkling, laughing eyes, had brought us some salmon in Rock Creek a few days before, and was under promise to bring us some more on Monday. Two or three of the others always stopped for a chat as they passed through. All of them, I noticed, were curious to see how King George’s man would act in this new capacity.(page 139)

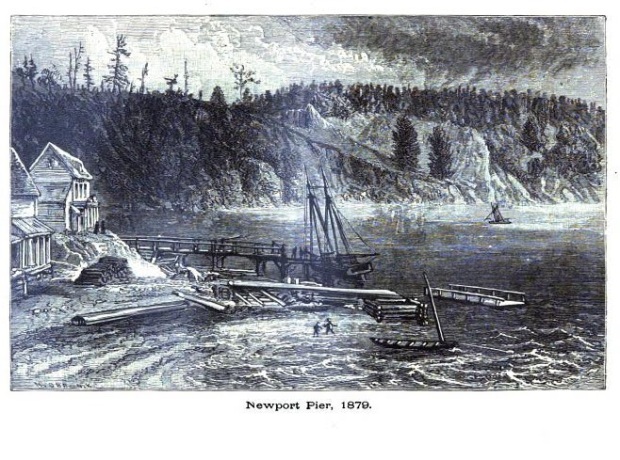

In the Newport area:

Flounder-fishing in the daytime is good sport. Find out the nearest camp of Indians there on the beach, crowded under a shelter of sea-worn planks, a few fir-boughs, and a tattered blanket; the smell of tainted fish pollutes the air, and a heap of flounders, each with the triangular spear-mark, attests the skill of last night’s fishermen. “Any fish, muck – a – muck?” say you, blandly. Without turning her head, or raising herself from her crouching posture by the old black kettle, stewing on a tiny fire of sticks in the center of the hut, the old crone grunts out, “Halo” (none). “Want two bit?” you say, nowise discouraged. Money has magic power nowadays, and she rises slowly and shuffles past you to where a rag or two are drying in the sun on a stranded log. From under the clothes she brings out a dirty basket of home make, and in it is a heap of greenish, struggling prawns. She turns out two or three handfuls into the meat-tin you have providently brought, holds out her skinny hand for the little silver pieces, and buries herself in her shanty without another word. (pages 83-84)