From Copenhagen to Okanagan, part 3

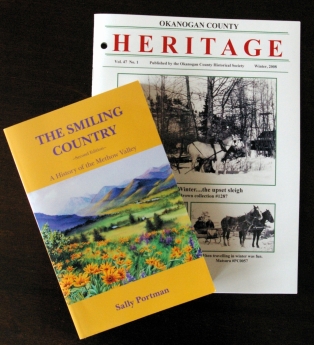

[See part 1 for full info on this fascinating memoir of life in the Washington Okanagan country, 1880s-1930s. It’s still in print, apparently, from Okanogan County Historical Society. Click the picture to visit their website. — Dave Robertson]

[There are more references here to sign language being used with Chinook Jargon, as in the last installment.]

Page 147-149: ‘On Saturday we had just quit working when “Miss Antoine”, as we called her, rode up. She stopped in the trail just a little way from where I stood, but the chaperone rode on about a hundred feet. I started toward the Indian girl to get the clean clothes and supplies, but she motioned for me to go back, saying: “Nika halo tikeh nanich mika pee nika tikeh nanich mika tillicum” (I don’t want to see you, but I want to see your friend)…When Anton [Kowalsky] came up she handed him the clothes and the provisions…she said to him: “Pee iktah mika tumtum kopa nika? Pee mika tumtum nika hiyu pootee?” (What do you think of me? Don’t you think I am very pretty?) Anton was stumped. He could hardly speak and understand English, let alone Chinook. He merely kept still, but his silence did not discourage her. She softly passed her hands from the top of her head down behind her ear to the back of her neck, saying, “Nanich nika latate” (Look at my head). She pointed to the red and yellow streaks [of “makeup”–paint or ochre–DDR] on her face. “Nanich! Nanich!” (Look, look). She extended her gloved hands, then let both of them slide down over her breasts and down to her knees, asking him again if he did not think her pretty. Then, apparently, she had reached the end of her act and had nothing more to show or to say, so she hesitated a moment. Anton was a long time in getting her meaning. “Hey, vot iss diss? You say you pootee?” She nodded vigorously, starting the same lingo. “Nawitka (meaning ‘yes,’) I think I’m awfully pretty.” “No! you no pootee! You dirty! Look!” he roared, pointing to his own face. You lot dirty. Go to de ripper [river] and wash yourself. You no pootee!” With a horrified glance at the object of her misdirected courting she turned her horse and clattered off, followed by my uncontrolled laughter. We never did see her again, for the next Tuesday her father [Antoine] resumed delivery of our goods.’

Page 150-155: ‘Early the next Saturday morning, bands of Indians began passing, all of them dressed in their finest clothes. I talked with two of them and they told me that they were all on their way to the mission to see the priest. They said that they had come from “pee hiyu siah” (long ways off)…they had a profound respect for Father [Etienne] de Rouge. The next day I varied the monotony of our Sabbath-keeping by catching a large trout. Anton lay in the shade as I set about cleaning it. Busy with the fish, I became aware of the arrival of three Indians, and old gray-haired man, an old woman, and, lastly, a young girl…The old man came straight up to me and immediately started to talk. I finished cleaning the fish, covered it, and then took part in the conversation. His name was Mountas, he said, and he pointed out that he lived on the Methow, saying it was “pee tenas siah” (only a short distance). I asked if the two “klootchmen” (women) were his wife and daughter, and he indicated that they were. he impressed me because he was more talkative and friendly than any other Indian I had ever met…he gave me the impression that he had been one of the warriors of Chief Moses…”Why are you and your family not with the rest of the Indians at the mission, Mountas?” I asked. His reply was rough with suppressed anger, “Nika halo tikeh priest” (I don’t like the priest). “Is the priest a bad man?” He hesitated a moment, then said, “Klonass, klonass halo!” (Perhaps, perhaps not!) “If you are not sure whether he’s god or bad, what has he done to you?” I could see that I had touched on a question that he did not care to discuss. He carefully thought over his answer before replying in his own tongue [Salish?! Chinook Jargon?!]: “A long ti-i-me [notice the expressive lengthening] ago, there were not many priests here, but many Indians. The squaws gave birth to many babies. Then the priest came. The squaws almost quit having babies. The Indians died. Soon there will be no more Indians.” “Do you believe that priests are to blame?” His answer was quick and firm: “Nawitka, pe nika tumtum kahkwa” (Yes, I believe so). [Fries discusses how along with the priests came traders with foods that Indigenous people didn’t know how to use healthfully, as well as liquor.] “Does the priest like you?” “No,” he shook his head decidedly…”Some time ago the priest came to my house and asked me to go to the mission to partake of Holy Communion. I said to him, ‘No, I don’t go to the missions to take eat [sic] with the Lord.’ The priest got very angry with me and told me that when I died my soul–” Here Mountas laid his head as far back as he could, looked straight up, put his hand close to his mouth, and blew gently through his lips, “Whe-e-w.” At the same time he raised his hand straight toward the sky. “When my ‘whe-e-w‘ (soul) ‘klatawa kopa Sahalee Tyee’ (travels to the Chief above), the priest says He will know I have been ‘hiyu kultus kopa illahee‘ (very bad on earth). Then he will gather a lot of wood and make a big pile of it. Sahalee Tyee will put fire to the big pile and put my whe-e-w on it and my whe-e-w will ‘kwonesum mitlite kopa okoke piah‘ (always stay in that fire).” “Did you answer the priest?” He nodded. “Yes, I told the priest that if Sahalee Tyee wanted to put my whe-e-w on the fire and keep it there it would be ‘hias kloshe‘ (all right) with me.”…She [Mountas’ daughter, whom Fries has just noticed] was really striking, both in her figure and dress. I don’t know how long I looked at her, but Mountas brought me back to thinking. “Pee mika iskum klootchman?” (Have you got a wife?) he asked. I shook my head, “No.” “Pee mika tikeh klootchman?” (Do you want a wife?) I did not grasp the meaning of the situation and unthinkingly answered, “Yes.” Then Mountas extended his right arm, saying, “Pee hyas Kloshe [sic] spose mika takee okoke klootchman” (It will be all right if you take that girl). I was dumfounded [sic]. I thought at once of what my mother and sisters’ reactions would be to my marrying an Indian girl…So I discarded any thought of accepting Mountas’ gift. “Pee iktah mika tumtum?” (What do you think?)) [sic] My mind was made up. I wanted only to keep from offending him and his daughter. I knew that her parents loved her and wanted to get the best husband for her that they could find. They probably knew all about Anton and me, and how we worked hard and did not drink…”Mountas do you believe that it would be right for me to take that girl–when I don’t know her and she doesn’t know me?” “Nawitka, nawitka,” he nodded emphatically. “That’s all right–if you take that girl and both of you go to the priest and have him talk to you and get both of you this way.” Here he locked both his index fingers together and pulled them strenuously without causing them to come apart. “Always stay that way and it will be all right.”…”I have already asked a girl to come to live with me, and if I take this girl now, and in three months the other girl comes, there is sure to be a ‘hias pite‘ (big fight). His face fell. “Pee okoke kloochman Siwash kloochman pee Boston kloochman?” (Is she an Indian girl or a white girl?) As he seemed determined to find out all about her, I told him that she was white. “When that white girl comes to your place, are you both going to the priest and have the priest ‘wawa kopa konamox, pee chaaco kahkwa (talk to you both and you become this way)?” Again he locked his fingers to indicate marriage bonds, and I said that we were. “Ah haw“, was all he exclaimed and he left at once…Later I inquired of Antoine, “Do you know a man by the name of Mountas who lives near here?” But he shook his head. “Pee nika halo kumtux okoke Siwash” (I don’t know that Indian) was all the answer I got.’

Pingback: Pooty good! | Chinook Jargon